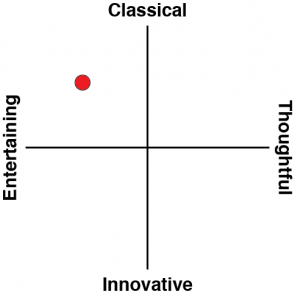

One of the things that I find continually surprising about video games is the idea that, on the one hand, we consider them to be inherently an art form, but on the other, we just never talk about games in the same frameworks that we talk about every other art form. Take for example the idea of the pastiche. We don’t really talk about derivative video games as “pastiches”. They’re typically called “clones.” It is a simplified equivalent with roughly the same meaning, but our inability to engage with the material in those artistic terms suggests that we’re not quite ready to really take games seriously yet. Anyway, the reason I say all that is that the most interesting thing about Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Splintered Fate is musing over its quality as a pastiche. It’s not particularly fun to play.

Over in the art world, “pastiche” is typically used in pejorative terms, but it doesn’t have to be inherently a bad thing. In the hands of a good artist, pastiche can become a technique for exploring ideas further, and even take on a transgressive, challenging quality. There’s an excellent thesis by Christopher Bell titled “Premonitions of the Past: An Analysis of Pastiche in the films of Quentin Tarantino,” that not only looks at Tarantino’s use of pastiche as a technique (famously, Tarantino is obsessively in love with film as a medium, and his work typically reflects the love that he has for other films), but also provides a good summary of just how complex the debate has become around the idea of pastiche in cinema:

“In her analysis of Richard Linklater’s work, Mary Hairrod proclaims that ‘Pastiche may be more fundamental to cinema today than any other time in the medium’s history’. That may be so, but the term itself is one that remains mixed in ambiguity. Frederic Jameson refers to pastiche as representative of ‘blank parody’ and argues that the ‘disappearance of the individual subject, alone with its formal consequence, the increasing unavailability of the personal style, engender the well-nigh universal practice today of what may be called pastiche’. In other words, he sees parody as having been replaced by pastiche, but at the cost of losing the ‘ulterior motives’ and ‘satiric impulse’ that constitute the most successful aspects of parody. Linda Hutcheon takes aim at Jameson by opposing his notion that pastiche and parody can be separated, as she stresses that both are unique and able to comment on history through political irony. She suggests that Jameson’s position is one too closely aligned with Marxist history and that he fails to consider other ways in which pastiche can be used critically. She argues that pastiche works through parody to “both legitimize and subvert that which it parodies” thus creating a critical dialogue between past and present.

“Many theorists have taken aim at Jameson’s views of pastiche, with Ingeborg Hoesterey and Richard Dyer publishing two of the most prominent works arguing in favour of the mode’s potential for purpose and meaning. Hoesterey, in her book Pastiche: Cultural Memory in Art, Film, Literature, asserts that postmodern pastiche is about cultural memory and the uniting of perspectives past and present, and that the mode sets itself in popular culture beyond a high-low dichotomy. She stresses that postmodern pastiche aspires to be art that demands critical thinking.”

That’s a lot of reading, I know, but if you skimmed over it, the overall point that it’s driving at is that when it’s knowingly used as a creative tool, pastiche doesn’t need to mean an empty and derivative, fundamentally worthless artwork that many people commonly associate with the word.

Unfortunately, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Splintered Fate has not been made with the oversight of a Tarantino (the video game equivalent might be Goichi Suda of Hideo Kojima). Before coming to console, it was a mobile game designed to give mobile gamers a Hades-like experience, and it never strays far from that mission to carbon copy everything. It is a roguelike where you’ll move from room to room, upgrading your character with every successful wave defeated. Every so often you’ll run into a boss, and eventually, you’ll hit an area that is just beyond you. Thankfully the progression system means that on your next run, you’ll be slightly better equipped, so you’ll make it slightly further, and so on.

There’s nothing wrong with a good roguelike, and Hades is a masterpiece, so if you’re going to blindly copy anything you may as well copy it. But Splintered Fate does absolutely nothing to engage with the TMNT property. There’s the bones of a narrative, sure, and you will get to control all four heroes and encounter many of the denizens on the way to take on Shredder. Best of all there is multiplayer, and if you squint your eyes really hard you can almost imagine that you’re playing a spiritual sequel to the brilliant arcade game from all those years ago.

It just doesn’t take long for the lack of energy in the action to drag on any enthusiasm you might have, though. Enemy waves are uninspired, and the range of enemies is limited. Sub-bosses and bosses are challenging, but have uninspired attack patterns and are tactically uninteresting to play. Each turtle has their own playstyle and plenty of skills to unlock, but when the action starts to get hectic its easy to lose the impression that you’re playing a Turtles game at all. That’s always the risk with a pastiche – the work you’re producing can lose its identity if the thing it’s aping takes over, and Splintered Fate looks more like Hades in motion.

Of course, it’s also not as good as Hades, since it’s blindly copying the Hades idea, rather than being made by creative people who had a vision (i.e. the Hades original developer). Hades has strong and compelling characters, an incredible, unique art style, blisteringly responsive action and a unique approach to roguelike design that separates it from all the other roguelikes. Splintered Fate has none of those things.

Ultimately, the best way to play Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Splintered Fate is in exceedingly short bursts. As a “switch your brain off and button mash” kind of experience it works and in so closely emulating Hades it is inherently entertaining. But it’s also soulless and draining to play for longer than a half hour here or there. It doesn’t even work as TMNT fan service since it behaves more like Hades. It is, simply, a pastiche that is simultaneously a decently made game but also a very bad creative work. If only the games industry were better at using the language to grapple with stuff like this.