One of the finest examples that I can think of that highlight the differences between Western and Eastern game development, and some of the weaknesses that we as a collective industry have in critiquing video games, is to look at Dante’s Inferno and El Shaddai: Ascension of the Metatron side-by-side. They were released at around the same time (Dante’s Inferno was 2010, El Shaddai was 2011). Both were a clear response to the impact that 2005’s God of War was having on action brawlers. And both shared a similar premise: Dante’s Inferno depicted a trip into hell. El Shaddai was a journey through the Tower of Babel towards heaven.

Dante’s Inferno ended up being quite a decent bit of entertainment (at least, I enjoyed it), however, it was a compromised one. The game was an effort to take the circles of hell and recreate them in as “authentic” of a way as possible, but then you realised that as the dumping ground for sin and depravity, this hell was not nearly hostile and unpleasant enough (of course, then Agony came along and we were reminded of just how niche the interest is in a truly authentic experience of hell). More importantly, however, the game engaged with the Dante’s literature on no meaningful level. It was simply a surface-level recreation of the most surface-level elements of the book. Sinners bad, Virgil’s your guide, hell is unpleasant. No one would play this game as a way of getting out of reading it for a literature essay.

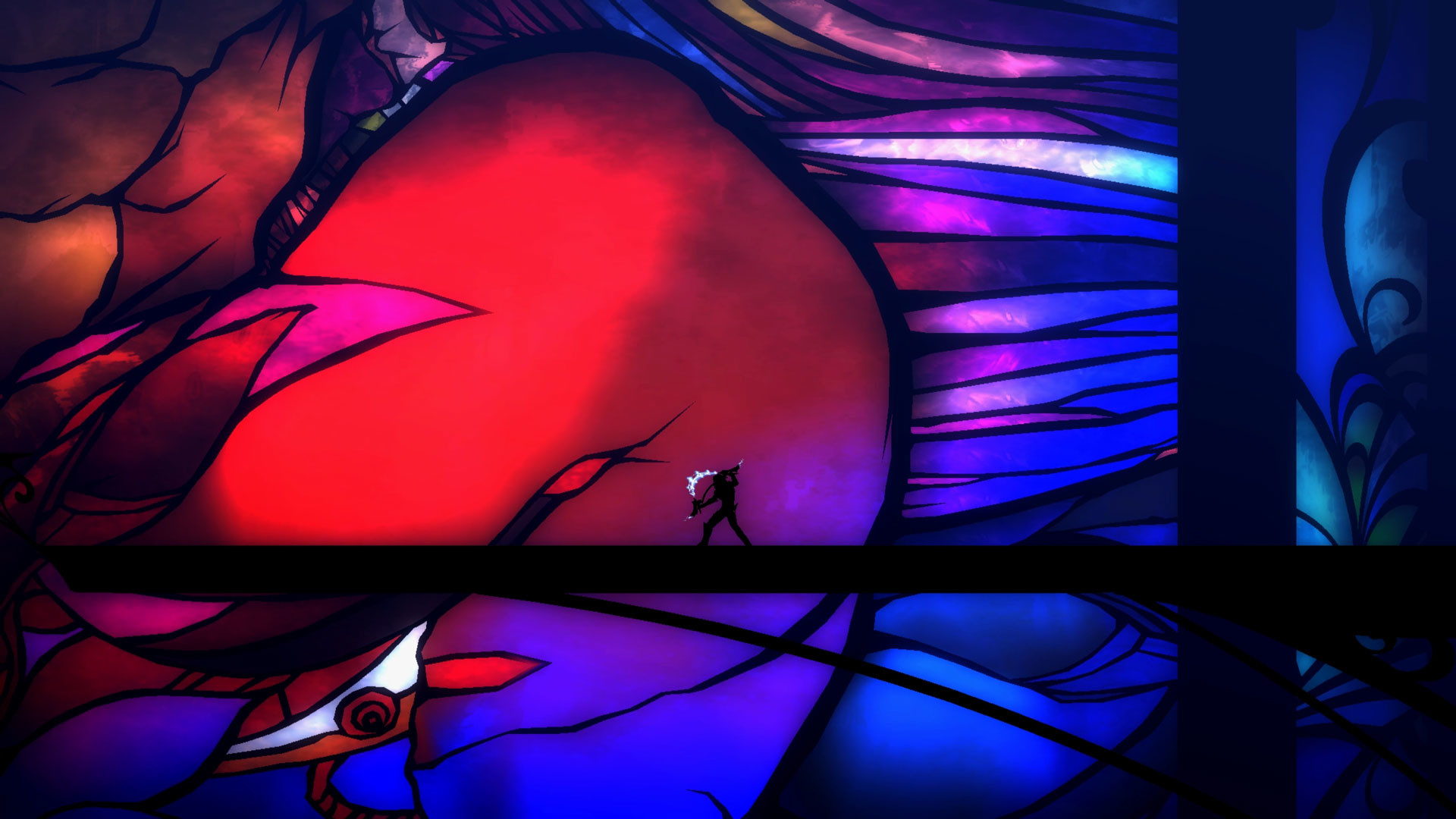

Meanwhile, El Shaddai might not have been a trip into hell, but it is drawing from a pretty dark text itself, given that the Book of Enoch was essentially a justification for the flood in Genesis and an explanation on the origins of demons and why angels fall from heaven. It might not be part of the “official” Bible or Jewish faith (though in some sects it is), but it’s a fascinating work that is referenced in the Bible even if it isn’t fully embraced. However, unlike the Dante’s Inferno team, the developers of El Shaddai were not even slightly interested in giving players a surface-level recreation of either the Book of Enoch or anything to do with the heavens (or the Tower of Babel, for that matter). Instead, this is one incredibly abstract work, filled with rich and complex visual and narrative metaphors. Thanks to that visionary work and the themes behind it, where Dante’s Inferno was a perfect fine and entertaining game to play (but is essentially forgotten about today), El Shaddai is a masterpiece that may have never sold that well, but certainly warrants ongoing study (and, frankly, to be put into galleries and museums).

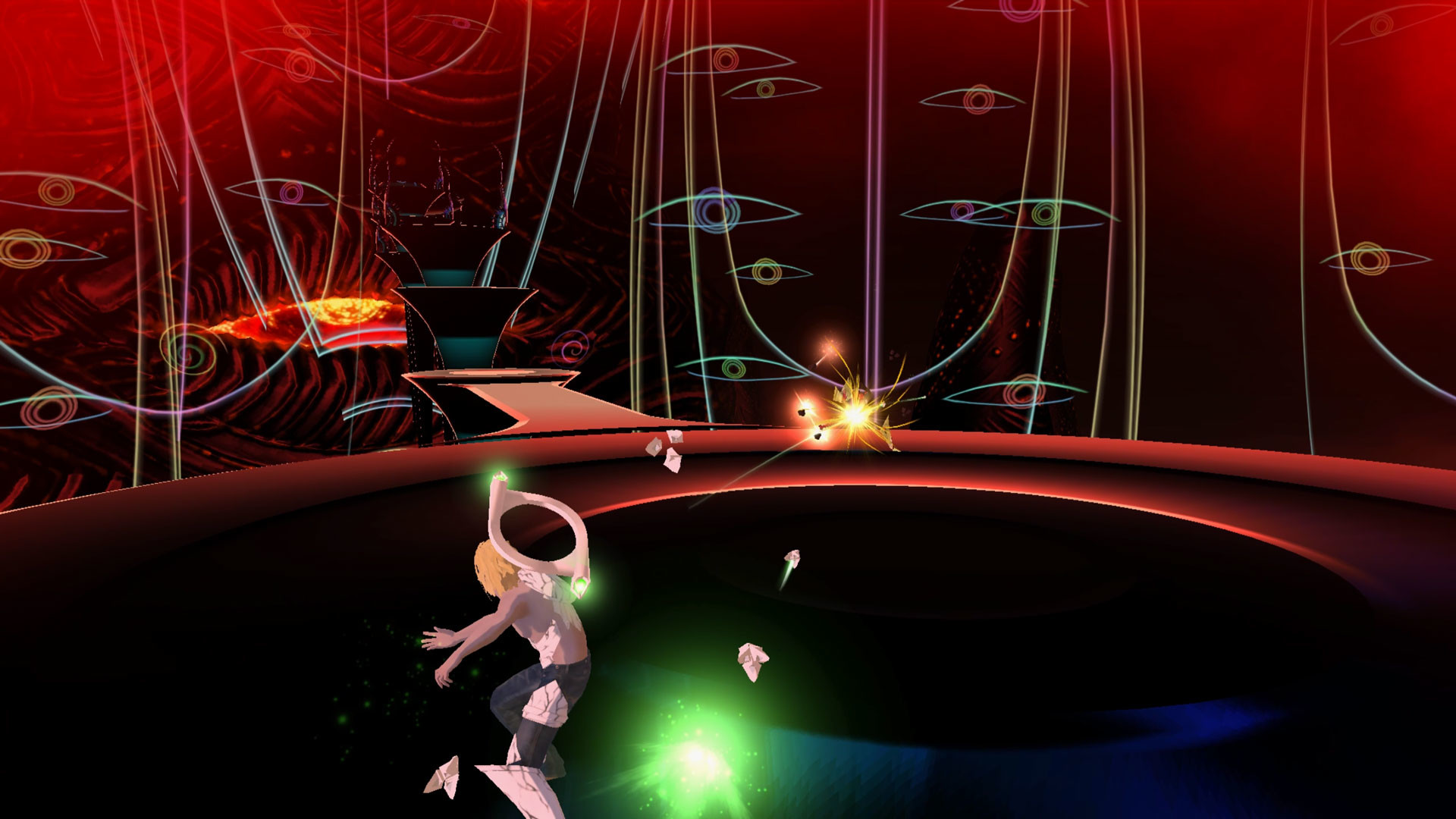

This Nintendo Switch port is really, really good too, if not a true definitive edition of the vision. Billed as a “HD remaster,” it runs at 60 frames per second, and the high saturation, high contrast colours look absolutely gorgeous on that OLED model of switch in particular. It might not be all that much of a game, and the shallow combat systems with limited progression features is even more obvious now than it was then. But then the combat is merely the frame. Something to flex the muscles between what actually mattered to the developers – the narrative and artistry. Playing it now, over a decade later, it’s easy to be reminded of just how much most critics miss the mark when looking at this game. Yes the combat system isn’t engaging and the decision to throw platforming sections in was unwise, but then you get to the critics that write things like:

“Following all of that, the game still has a nonsensical and overly pretentious narrative. Not only in how it’s communicated but also in how it is visually depicted,” or “There’s never any clarity in El Shaddai, and it’s a huge problem.”

I’m sorry, but no. We need to stop letting “it doesn’t make sense” be a legitimate criticism from professional critics, because that’s not a professional criticism. Unless the game literally doesn’t make sense through a broken translation, it’s your job to make it make sense. “It doesn’t make sense” are criticisms that are leveled at so many other games that grapple with complex ideas. Lightning Returns (as in the third in the Final Fantasy XIII series) or NieR Replicant (before NieR Automata made everyone go back and actually pay attention the second time around) have also been frequently criticised by people for “not making sense,” much to the bemusement of anyone that does understand what they’re talking about.

“Not making sense,” is a you problem, not the game’s problem. Romeo & Juliet and Hamlet “don’t make sense” to a lot of people, but that’s not a weakness in Shakespeare. 2001: A Space Odyssey confuses a lot of people. That’s not Kubrick’s fault. The entire art form of doesn’t make sense to a lot of people that seem to think it matters if they understand the lyrics and most operas are in one “foreign” language or another. No. It is not the problem of the entire art form.

If you want to criticise anything for something like El Shaddai “not making sense,” then point fingers at the education system. Doubly so for this game, in comparison to some of the others, because as far as “high concept” stories go, it’s not even that difficult. El Shaddai canvasses the relationship that people have with religion and the nature of corruption. One of the core gameplay mechanics is for you to ritually purify your weapon to be able to continue to damage enemies, and you’re being led around by Lucifel. It’s really not a hard theme to follow.

Then there are themes around personal freedom versus blind obedience, and the notion of self-sacrifice. There’s a strong rejection of ideas of perfection and the divine – Lucifel even suggests that the player reject the idea of an angel in dazzling armour to fight in something far more human – jeans (this is also a self-reflective satire, given that Devil May Cry’s hero was running around in jeans at the time). There are fourth-wall-breaking moments and constant efforts to deconstruct the concept of the holy. If there is something at fault in El Shaddai it’s that the game makes a habit of introducing themes only to fail to explore them to their full extent. This allegedly comes down to a difficult development process that left too much on the cutting room floor, but that doesn’t mean that it’s confusing on any level. It’s all there, it just doesn’t fully engage with its own ideas.

It’s one thing to come across a trolling user review that dismisses a game like El Shaddai for “not making sense.” User reviews don’t filter who gets to leave them. However, when it’s the critics doing it, it’s like having an art critic wander into a Monet exhibition, see the famous Lilies painting, say “I don’t get it/too confusing,” and give the thing a 0/10.

Perhaps if we had more critics that were capable and willing to engage with games that have a higher concept, like El Shaddai, we would have more developers making them, and fewer treading over the same “FPS 101” or “Open World Quest Structure For Dummies,” games that inevitably score higher on Metacritic because they treat players like idiots and spoon-feed everything to them.

The fact that El Shaddai has been remembered as a cult classic (albeit with a fleetingly small cult) that has never been replicated, while its immediate peer from a decade ago has been relegated to the deep collective memory of “content that was kind of fun, I guess, but I have new toys to play with” highlights which of the two we, as a collective, should be trying harder to encourage more of. We need to stop acting like “complexity” (i.e. some abstract ideas and the occasional metaphor) is an inherent flaw.

By purchasing from this link, you support DDNet.

Each sale earns us a small commission.