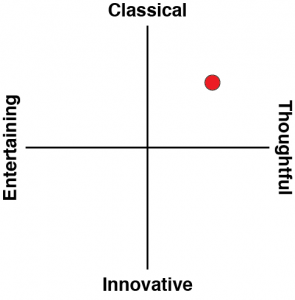

Australians should make more visual novels. I don’t just say that because I make them and need to kick myself into actually finalising my latest one (it’s getting there, day by day!). It’s just that whenever an Australian produces a VN, it’s typically gold. Max’s Big Bust is a hilarious series that so effectively melds Japanese fan service with Australian cultural humour. Quantum Suicide is the best Danganronpa this side of Danganronpa. And now there’s Corpse Factory, which was developed by a team down in Melbourne, and gives Death Mark and Saya No Uta a run as the best horror-themed VN I’ve ever played.

At first, it’s going to seem like a pastiche of the anime/manga Death Note. There’s a Website that people can jump on, upload a photo of someone, and a few days later that person is going to turn up dead. Not only that, but the victims know it’s coming because they actually get a photo of their dead body sent to them ahead of the fateful day. All is not what it seems though. There’s nothing supernatural going on here. This is not a spoiler (it’s revealed in the first chapter), but the Website is actually managed (anonymously) by a woman named Noriko. By day she’s a mild-mannered, low-level data entry peon for a major bank, struggling to make ends meet on an inadequate wage. At night, however, she is a malevolent prankster. She takes the photos that are sent to her via the Website, digitally superimposes them on to photos of bodies that she finds from an online resource, and sends it to the victim.

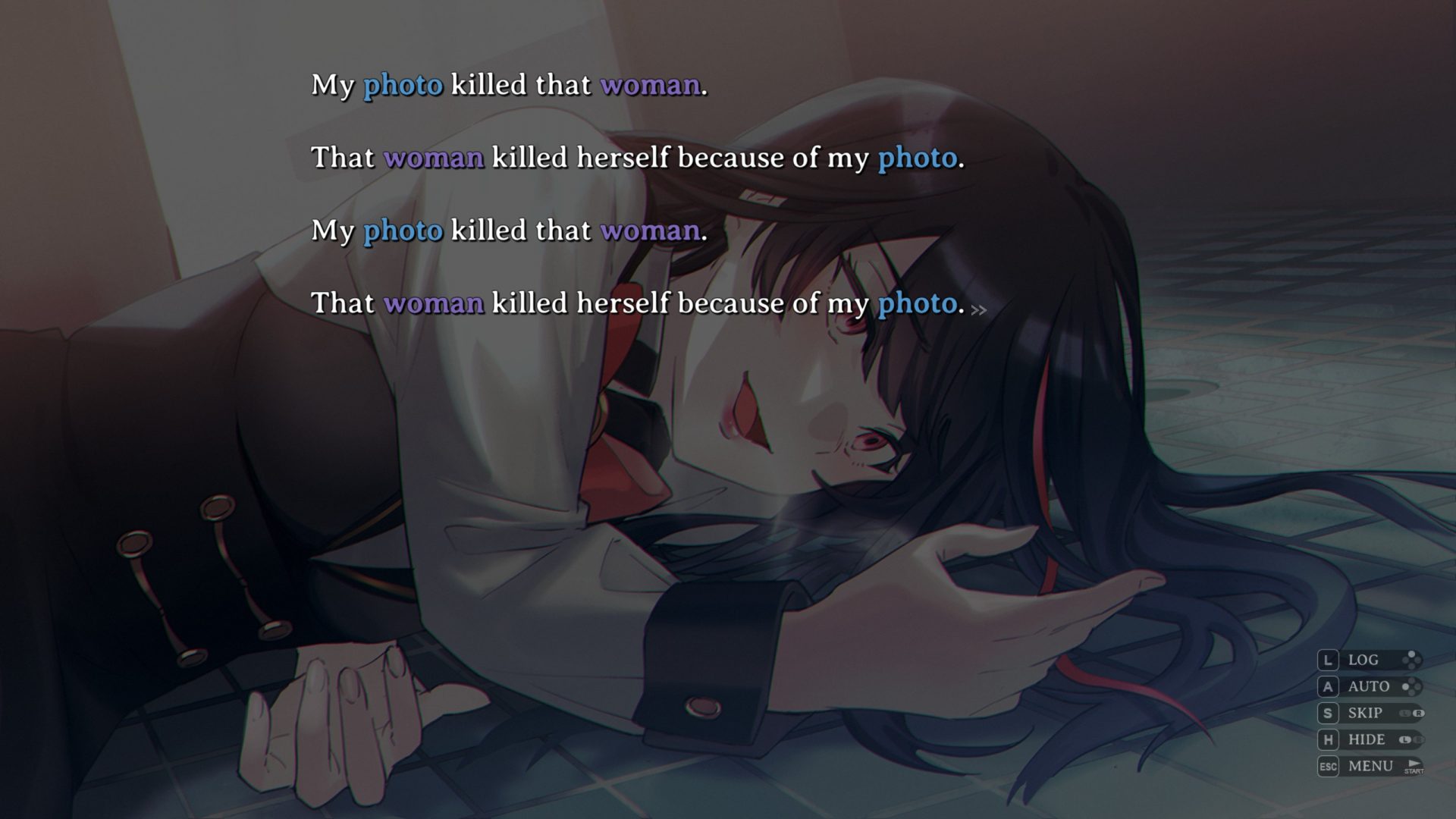

Often, they’re so utterly shocked and terrified by seeing a photo of “their” dead body that they do something dangerous or suicidal, and subsequently cause their death to actually occur. And, when Noriko discovers that she has caused someone to die, she comes.

You read that right. She has an orgasm. Something the game’s writers spell out in such explicit language that a hentai visual novel would be proud of the description. You don’t see anything visually – this is not hentai – but like Death Mark and Saya No Uta that I mention above, this is one of those rare games that explores the link between eroticism and horror to any meaningful degree. It’s not an accident within the writing, either. After one murder, Noriko is disappointed to find that she didn’t come quite so hard that time, so it’s clear that this perverse, sublime arousal is the goal of her activities. Video games are a unique art form in that horror and sex are not often linked together, but as long as horror has existed in literature, cinema, and elsewhere, that link has been explicit, as filmmaker Michael Varrati put beautifully in this interview: “Horror, by its definition, is a genre of subversion. It often utilizes the lens of the fantastic to shine a light on things we don’t feel comfortable tackling directly.”

Corpse Factory is particularly subversive because it’s simultaneously inviting us to be empathetic with Noriko – outside of her hobby she’s presented as a mild-mannered person that is the victim of violent bullying, is deeply in love, and is a good neighbour. Her descent into depravity and madness is a consequence of her situation, and we’re meant to be sympathetic towards that, too. The juxtaposition between the sadism and the rest of Noriko makes her a fascinating, transgressive character, and one well worth studying.

The sheer transgressive nature of this eroticism, and its extreme breach of the taboo, immediately called to mind Georges Bataille, one of the pre-eminent philosophers of eroticism and transgression. In his book The Story of the Eye, Bataille wrote: “To others, the universe seems decent because decent people have gelded eyes. That is why they fear lewdness. They are never frightened by the crowing of a rooster or when strolling under a starry heaven. In general, people savour the “pleasures of the flesh” only on condition that they be insipid. But as of then, no doubt existed for me: I did not care for what is known as “pleasures of the flesh” because they really are insipid; I cared only for what is classified as “dirty.” On the other hand, I was not even satisfied with the usual debauchery, because the only thing it dirties is debauchery itself, while, in some way or other, anything sublime and perfectly pure is left intact by it. My kind of debauchery soils not only my body and my thoughts, but also anything I may conceive in its course, that is to say, the vast starry universe, which merely serves as a backdrop.”

Essentially what Bataille argues through the book is that eroticism – extreme eroticism, at that (Bataille wrote extensively of Marquis de Sade) – was a pathway to a kind of enlightenment, and that only by transgressing and breaking taboo we can come to a kind of introspective knowledge that fully understands and appreciates the existence of the taboo. Elsewhere in The Story of the Eye, he wrote: “That discourse one might call the poetry of transgression is also knowledge. He who transgresses not only breaks a rule. He goes somewhere that the others are not; and he knows something the others don’t know.”

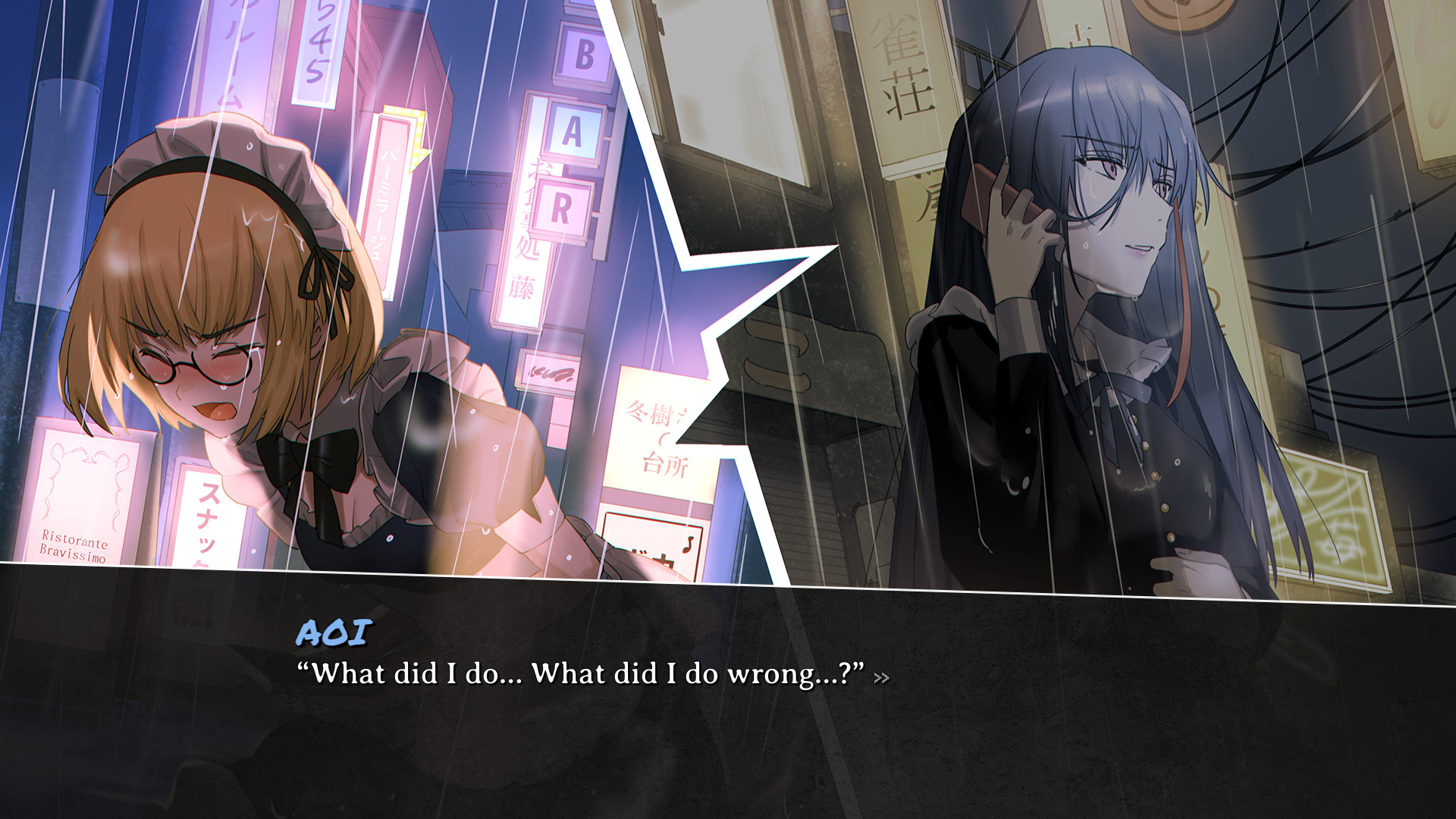

Sade epitomised this. His writing was a truly brutal and depraved assault on the senses, but it wasn’t senseless. This was Sade’s way of attacking the vile decadence of France’s elite at the time, remembering that Sade was, politically, part of the revolutionary movement in France. Likewise once you cut through the extreme qualities of Corpse Factory, it becomes clear that it is a story of disenfranchisement and a broad critique of the socioeconomic factors that lead someone to become disenfranchised. It’s a world where the middle management bullies those they can lord power over, that the low find themselves so fiercely competitive with one another that they turn on each other, and that the upper echelons exist in seemingly untouchable ivory towers. I could go on, but the point is that Corpse Factory is sharp in its observations. It’s not just eye-opening for shock value. It has something to say and while (or, more accurately, because) it’s sadistic rather than subtle, you’re also not going to be able to tear yourself away from it.

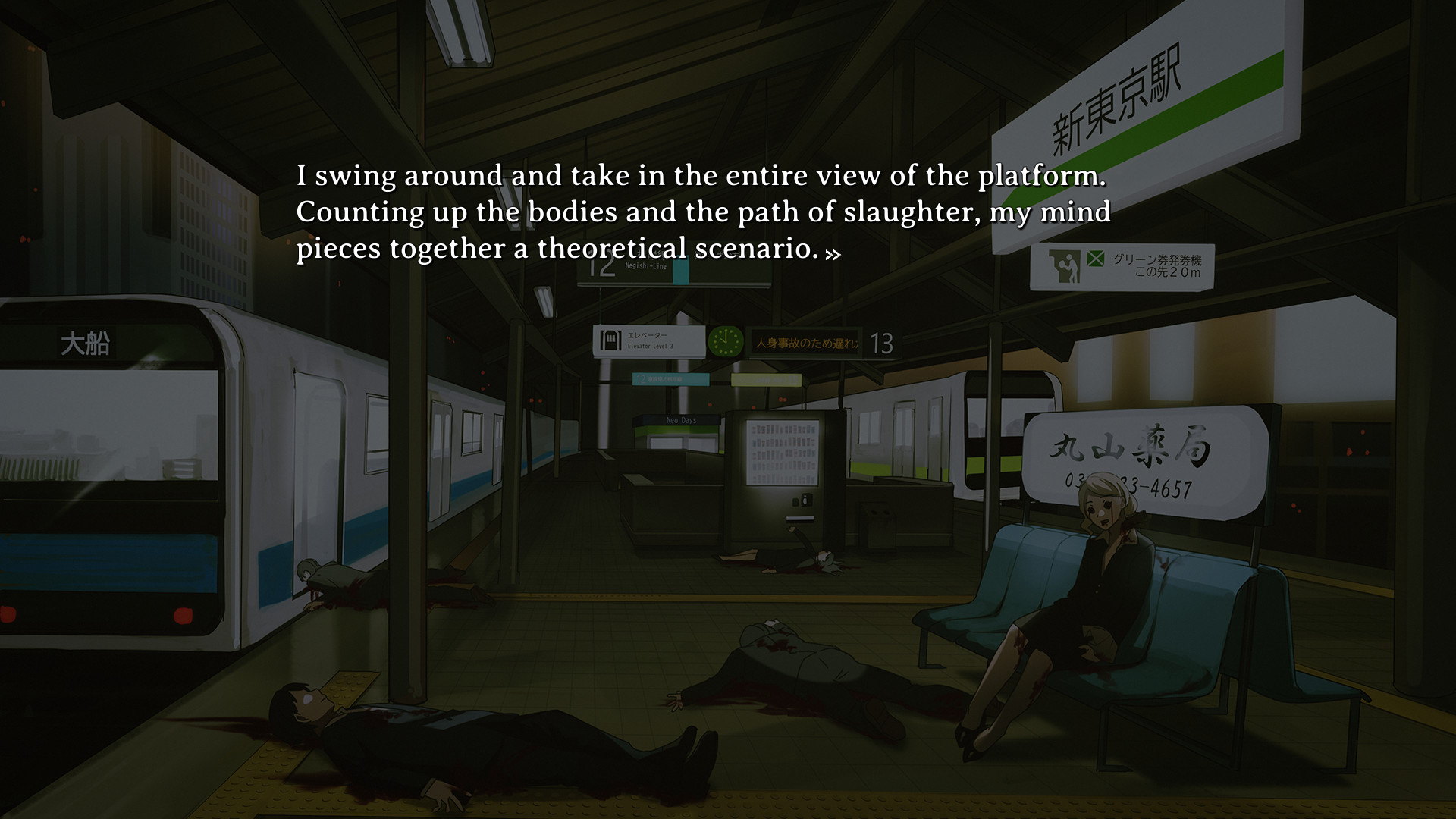

It works as a viscerally entertaining page-turner, too. Early on in her career as the “Corpse Girl,” someone sends the website a photo of Noriko herself, and there the VN picks up a mystery edge. There are innocents in the story and you will expect horrible things to happen to them, but you won’t be able to stop reading anyway. The game moves on at a brisk pace, but still takes the time it needs to paint a vivid scene and explore the quirks of a quirky bunch of characters in full (and eventually moves away from such a pure focus on Noriko to let you see events from the perspective of other characters, all of whom are also deeply morally compromised in one way or another). Will Noriko continue to get herself drenched every time she causes a death? Are people going to figure out the story and “trick” behind the website? When will the authorities get involved and will Noriko be able to outsmart them? Just how are the other characters going to get involved? What I’ve described in this review above all occurs in just the first couple of hours, and you’re going to press on through it because between the twists and turns and the mysteries, this game raises more questions than it answers.

As a game, it’s a very straightforward visual novel, with just a few decisions to make along the way (three, from recollection). I’ve only played Corpse Factory through once but I imagine that there will be multiple endings based on these choices. In terms of presentation, meanwhile, it’s not quite the aesthetic masterpiece of Death Mark or even Saya No Uta. Corpse Factory’s art is fine, but it’s very clearly indie in scope. It’s also poorly optimised for Switch. For example, there were times I had to revert from buttons to the touch screen because the interface seemed to break, and despite being a modest VN there are some very long loading times. Finally, while the game games off as authentically Japanese (I didn’t even realise the developer was Australian until sitting down to write this review), there’s no Japanese voice track. The actors do a decent job here – especially Noriko – but still, I would have appreciated a Japanese voice track option to match with the rest of the aesthetics and presentation.

Corpse Factory isn’t about the presentation, though. This is a visual novel with a transgressive and provocative story to weave, and it does so with some of the deftest writing we’ve seen in the genre. We really do need to see more visual novels come out of Australia and, more generally speaking, games that are genuinely willing to break taboo subjects and really challenge the player.

There’s eroticism in death mark? 🤨

Yes. I wrote about it in my review. A lot of the art and theme in the game was highly fetishistic: https://www.digitallydownloaded.net/2018/11/review-death-mark-sony-playstation-4.html

I remember you talking about it now that mention it but I didn’t notice when I played it.