The Order: 1886 is at its best when it’s not trying to be a game. The development team wanted to deliver a highly cinematic, narrative-driven experience, and in literal terms it achieved this. The Order: 1886 is, indeed, a narrative-driven experience.

So before we get on to the game side of things, let’s talk about that narrative, because while it’s the better half of the game, it’s not even close to something essential. What we’ve got here is a very odd mix of Arthurian themes, Victorian London, and the Underworld film franchise. I wish I was joking about that latter bit, but that really does seem to be where the game derives a lot of its narrative inspiration from, and the first time we see a werewolf transform from human into beast, it’s an almost exact replica of the transformation sequence in the Underworld film.

And within that context we have all kinds of other narrative quirks that seem to be thrown into the mixing pot for no other reason to make the game more fantastic, more overblown, and more “cinematic.” There’s a lot of name dropping going on, with people like Nikola Tesla playing bit roles in the drama. Tesla doesn’t pick up weapons and join your team’s fight against the underworld, but he supplies the weapons, behaving very much like Q from the James Bond franchise in the process. I seriously expected him to hand my “knight” an exploding quill and supply an invisible horse-drawn carriage.

It’s admirable that the development team wanted to create a fantasy Victorian England with a relatively high level of technology, and a secret order of knights and an even more secretive order of villains. It’s a little dapper, and it would almost work if there was any consistency to the tale, but sadly there isn’t. For all its promises of a cinematic experience, The Order 1886 still has very little interest in doing anything more than driving players to the next shootout. It’s all about the big explosions and bigger moments, and that love of violence and visceral action marks it out as be a student of the Michael Bay philosophy toward cinema design, but at least Bay has the clout to trick A-list actors to his projects. The actors that have signed on to this project are sadly unconvincing, one and all, and it was difficult not to tune out during the dialogue sequences.

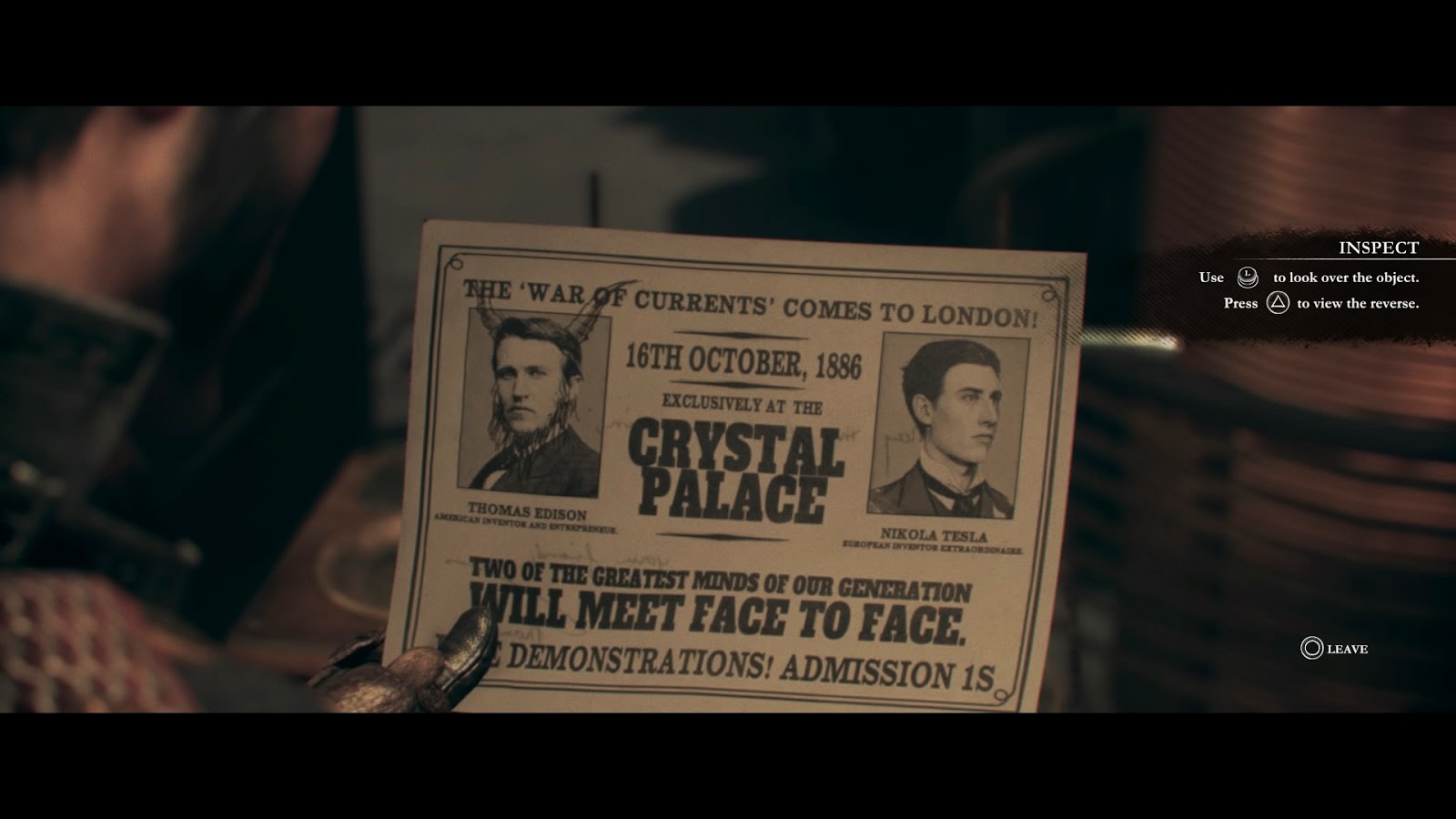

The real winner was the environments themselves, and especially Whitechappel. Victorian Whitechappel was one of the most infamous slums, and for good reason – it was a place of black smokes, cobblestone paths, and worn, weathered, filthy buildings. Those moments where Ready At Dawn allowed their clear love for the era shine, it was genuinely impressive stuff. A flier that Tesla and his intellectual nemesis, Thomas Edison has been defaced by Tesla in a tongue-in-cheek reference to the drain Edison put on the man’s career. Walking through a building you’ll see people sleeping while sitting in uncomfortable seats, held up only by a rope strung across the seat. This actually happened. Streets, architecture, clothing – these things are all quite carefully modelled after the real history so that, while the narrative is a fantasy, the location it takes place in is not.

That authenticity is why I am so confused that when it comes to the action, Ready At Dawn lacked the confidence to use weapons drawn from the period. Thanks to Tesla, players have access to weapons that behave almost exactly the same as you’d see in a game like Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare. Rapid firing pistols, fully automatic rifles, sniper rifles with extreme scope, grenades and bombs. The moment a combat sequence starts up you’ll forget the setting entirely because it’s couldn’t be more out of sync with the weaponry. It’s not the stock standard cover-based shooter mechanics that offend me. It’s not even that combat arenas are filled with conveniently placed objects to hide behind that don’t make sense in the context of the environment. No, what is most irritating is that the developer went to the effort to research and recreate a setting, only to use Tesla as an “out” and lazy alternative to trying to find a way to make relatively primitive weapons work in an action game.

Equally problematic is how overbearingly linear The Order: 1886 is. There is only one path through the game, and corridors were already claustrophobic courtesy of the layout of Whitechappel and other buildings of the era. When you’re not in combat situations, your character is restricted to the slowest pacing when moving about, which one assumes was to force players to take in the scenery and atmospherics, but has the effect of reminding players of just how limited the engine is. Other than picking up the very rare item scattered around the place, there is no way to interact with other characters in the world, let alone the environment. Pretty The Order: 1886 might be, but it is a very unnatural and artificial kind of prettiness that you’ll never feel like you’re a part of while on this adventure.

As mentioned, combat is of the generic cover shooter variety, where players will come across a combat room every so often and need to dispatch hordes of enemies. With hordes that are too large combat is too protracted to be fun over the long term, and if the enemy happens to overwhelm you right at the end of an encounter, the fact you’ll need to play through it again is draining, even if the checkpointing system is incredibly generous.

And then there’s the quick time events. Oh does The Order: 1886 enjoy its quick time events. These also feel like a lazy escape for the developers, who couldn’t think of a better way to show a desperate struggle to the death. It’s like the team understood that the cover shooting system, though functional, lacked the cinematic impact they really wanted, but at the same time understood that an entire game of QTE’s wouldn’t fly either, so they instead used them as many times as they thought they could get away with.

It’s important to note that nothing is actually wrong with the way that The Order:1886 plays. It’s a perfectly functional cover-based shooter, with tight mechanics and guns that have just the right weight and impact behind them. Enemies move about the place well, and display just enough AI that they’ll at least attempt to out-manoeuvre you. Everything right from the textbook of “how to make a quality shooter” is followed faithfully here, and so it distinguishes itself from truly horrible examples of the genre.

I also have no problems with cinematic games; I found everything from Beyond: Two Souls to Life Is Strange to be remarkably cinematic. I’m also comfortable with the game’s length, which is extended enough to tell the story it wants to tell. What I have a problem with is inconsistent narratives, and “gameplay” that has been so compartmentalised from the “story” that they may as well be in different products. The Order: 1886 had every opportunity to make something of the Victorian setting, but calling it cinema is like calling 50 Shades of Grey literature.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld