I must admit, I do feel like I’m running out of things to say about developer Gust’s Atelier Dusk series. That’s not to say the games aren’t worth writing about, but with Atelier Escha & Logy Plus, this is now the fifth time I have written a review for a game in this trilogy, the second time for this specific game, and I don’t really want to repeat myself when I’ve already got reviews for you all to read.

Related reading: Please check out Matt’s review of the PlayStation 3 original. It supports the content of this review.

But that’s also not to say I wasn’t happy to have an excuse to play through this game again. It’s one of my favourites in my favourite JRPG series, bar none. With the exception of Atelier Meruru (and, speaking frankly, that’s more because Meruru herself is something special rather than anything about the game itself), Escha & Logy is the one that I would rank as the finest in the series’ long history.

This is for a couple of reasons, but key among those is the way it deftly manages to balance out the series’ most central mechanic: the time limit. Atelier games basically work in a turn-based fashion, where every key action that a player does chews up some time. Time consuming actions come in multiple forms; whether it’s combating an opponent, exploring, gathering materials, or cooking those materials to form various alchemical items (that are either needed for quests, or to boost your party’s effectiveness in combat). It’s incredibly difficult to meet every objective with the amount of time that you’re provided in the game, and this has been both a blessing and a curse in prior Atelier releases. It was a blessing because it provided plenty of replay value for fans, as they desperately tried to maximise their use of time, but it has also been a curse to newcomers because it was initially quite intimidating and stressful to know that you have an awful lot to achieve in each in-game year’s time, and those objectives were thrown at you in such a way that you had many different things vying for your attention to work through.

Gust knows that this time mechanic is off-putting for some people, and in Atelier Shallie, the sequel to Escha, the development team removed it completely. Though I love Shallie, I felt that was a bit of a misfire as a decision, as the game lost some of its depth in losing the time management. I also felt it was unnecessary because Escha handles time so incredibly well and every Atelier game from now on should just copy this approach. Goals are broken down into much smaller, more manageable chunks, and while the narrative takes place over a great span of time, from a gameplay perspective you’ve only really got your eyes on targets a couple of weeks ahead at a time. By focusing the player with more immediate goals Gust is able to maintain its time management feature, while making goals clear and attainable for players.

Additionally, some of the other Atelier games can fall into ruts where the end goal is still in the distance, but the immediate challenges are under such perfect control that each in-game “day” is a case of going through the motions. By constantly refreshing the player’s targets, as Escha does, they are kept far more involved in the game at every point in the journey.

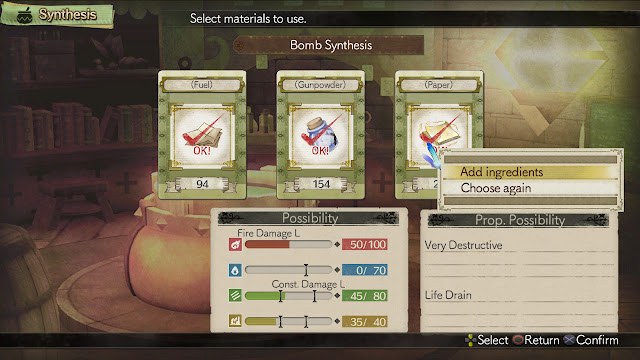

I am also a fan of the way that alchemy works in this game. In previous titles learning how to actually mix ingredients effectively in order to produce better results was a lot of busywork, involving grinding (to try and harvest better quality materials), and then experimentation (to learn how a “traits” system works). After your first couple of Atelier games, this system would make sense, but I distinctly remember having far less fun with the series at first as I tried to get the hang of things.

I wish I had have played Escha & Logy first, all those years ago. With clean, clear tutorials and a menu interface that presents the information in a way that makes a lot of sense, Escha & Logy is the most accessible of the series’ alchemy systems, and it would have saved me a couple of restarts in the other Atelier games while I got to grips with the system. I know that some purists consider what Gust has done with Atelier Escha & Logy to be a “watering down” of the experience, but I don’t really have an opinion on that, as I have never played an Atelier game for its complexity. I’m in it for the characters, narrative, music and general experience. For me, it only makes sense for the mechanics to be ‘simple’ to match, because otherwise they’re actually getting in the way of the reason that I’m playing.

Which brings me to the real magic of Atelier Escha & Logy; that narrative… it’s near on perfect. The three Dusk games all share a similar theme in that the world is drawing to an end, with an apocalypse in the form of a progressing wasteland swallowing up everything around it. The last vestiges of humanity cling on in crumbling societies on the fringes of this waste, and scrape by with what little is left to them.

But, in a twist that could only come from Japan; this apocalypse is no place for hatred, politics, and power games. It’s not the kind of violent end to humanity that franchises such as Fallout or Mad Max posit. No. Dusk is a more serene and almost accepting of the inevitability of the end (yes, nihilism. I’ll save that for another Game Theory though). The people have banded together to try to co-exist the best they can with limited resources. They’ve become content with what they have left. If a game like Fallout 4 is an angry reaction to the reliance that modern society has on gluttonous consumerism, Escha & Logy is the gentle suggestion that perhaps life would be better were it more simple.

This is mixed in with a certain sense of sadness for the inevitability of everything. After speaking to the director of the Dusk series, Yoshito Okamura, for my book, I discovered that the setting was inspired by the earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in 2011. The way Escha & Logy presents the sense of inevitability and the inescapability of the end of times is a poignant insight into the Japanese mindset, and the determination of the characters to make a life for themselves in the face of such hardships, is a resoundingly proud reflection on the stoicism of the Japanese people.

I’ve commented in the past that I prefer when apocalyptic stories look at the world as something other than a degeration of the human condition. It’s not that I’m opposed to the likes of Mad Max, but I find narratives such as Everybody’s Gone To The Rapture to be so utterly affecting because they do reflect on the vulnerability and fagility of humanity, even as they also explore humanity’s capacity to come together in periods of crisis.

But the serious side of things aside, Escha & Logy is also one of my favourite JRPGs of all time because Escha is one completely adorable kitten. Anyone who has not yet been inducted into the Atelier franchise won’t necessarily care about its heritage in protagonists, but each game is typically led by a female hero, and typically they’re ridiculously cute. Escha is firmly part of that heritage; she’s tiny, for a start, with most of the other characters towering over her, and between the pigtails, and the tail that she has hanging off her skirt (which is there for a reason, and animated, but no, she does not have a tail) her design is the right kind of mix of light, non-sexualised fan service of a kind that can’t possibly offend anyone rational, and charmingly sound anime character work. Gust has always had some of the best artists in the business, and in Escha we see them at their finest; here is a character who appeals both to the hardcore otaku and people who prefer their designs to be a little more subtle, and that’s a rare feat in an industry that doesn’t generally reward subtlety.

Escha’s other half, Logy, is an alternative option if you really don’t want to play a game as a woman. If I’m being brutally honest here I didn’t actually bother playing through the game as Logy. Catching his character arc on the PlayStation 3 original was enough. It’s essentially the same story, with a couple of minor conversation changes. Either way, the character you don’t choose is still your main partner through the adventure.

The supporting cast are a fun bunch as well, and the environmental design supports the melancholic tone of the narrative perfectly. The game doesn’t quite work as well on the PlayStation Vita as it did the PlayStation 3, with a level of detail lost, and frame rate stutters about the place (especially when the camera pans to show off a new area before a cut scene), but these issues don’t impact on the enjoyment or playability of the game at all, and the characters each have such vibrant personalities that very little of their underlying appeal is lost in the downgrade to the handheld.

What you will want to do, however, is jump online and download the Japanese voice track DLC. The base game was too large (in terms of raw GBs) to actually come in under Sony’s PlayStation Network size limits for Vita releases, so Koei needed to slice the entire Japanese voice track off and offer it as a separate (free, one assumes, though I have yet to confirm this) DLC download. You’ll want this because, while there’s nothing inherently wrong with the voice actors, they do a generally poor job in reflecting the character’s personalities. The Japanese voice actors, from my time with the PlayStation 3 edition of the game, are vastly more appropriate.

The combat is a very traditional turn-based affair, as standard for the series, and Koei hasn’t made any changes to that here. Each character in the party has a separate set of skills that they learn automatically through accumulating experience, and this means they all have different pre-set roles on the battlefield. There’s a complex assist system in place, however, which allows allies to help one another in either surviving enemy attacks, or doing more damage to them, though it’s a limited-use resource, so you’ll need to be strategic and use it only at the most important moments.

As with all games in the series, alchemy plays a big role in success against the more difficult enemies. Escha and Logy can both craft everything from armour and weapons, to bombs and healing items, and while the time it takes to craft these is time that could also be spent completing quests for other characters, the power they add to your side in a scrap is significant.

I do, however, like that in all Atelier games, you really don’t have to focus so heavily on combat if you would rather complete quests in other ways. Though it’s inevitable that there will be some conflict, it is nice to have a JRPG that doesn’t put it at the centre of everything. I generally pick a fairly pacifist route; not because I find the combat system unenjoyable, but simply because fighting is so much of the experience in other JRPGs I almost see the Atelier games as a break from that.

If you haven’t played an Atelier game yet, then you absolutely must go out and do so. As much as I love Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest and Shin Megami Tensei, as soon as I played my first Atelier game, I had a renewed passion for the genre. Escha & Logy actually works as a first point of call for the series. There’s very little assumed knowledge brought over from the first game in the Dusk series (Ayesha), and the systems and mechanics are more user-friendly and accessible.

Related reading: Matt’s other favourite Atelier title is Atelier Meruru. His full review here.

Plus, Escha is adorable. And you can’t exactly say no to her, because that would hurt her feelings. So do yourself (and her) a favour, and go grab it for your Vita now.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief