Review by Matthew C.

If you go into Virginia expecting a crime drama, you’re going to be disappointed. Yes, it’s centred on a pair of of FBI agents looking into the strange disappearance of a young child, but that’s really just a frame for the far more interesting story at Virginia’s core – a story of one woman’s struggles to navigate the the complexities of bureaucratic corruption, trust, conspiracy, integrity, institutional racism, and friendship.

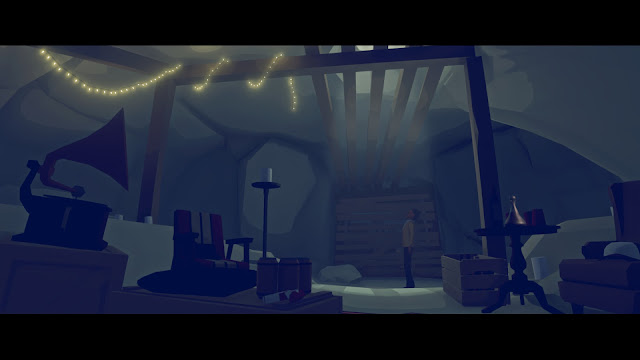

You witness the unfolding narrative through the eyes of Anne Tarver, a freshly minted agent paired with seasoned detective Maria Halperin. An investigation into the disappearance of Lucas Fairfax takes them to Kingdom, Virginia, a sleepy little town that’s not accustomed to having detectives snooping around. It’s noteworthy that Virginia has two women of colour at the centre of its story, because institutional racism is a key theme of the game. The FBI remains an organisation dominated by white men today, but this was even more the case in 1992, which is when Virginia is set.

Through their developing partnership, Anne and Maria find solidarity with one another, but they also have very unique ways of dealing with the pressure that comes with their position. Anne, at least initially, is a by-the-book rookie detective struggling to find her place within a toxic work culture; Maria’s committed to the pursuit of truth and justice regardless of how much of an outcast that makes her. It sounds like the makings of a bad buddy cop movie, but the friendship that blossoms between Maria and Anne is a deep and nuanced one. It’s also one that’s frequently threatened by the bureaucracy of the FBI, a seemingly dead-end investigation in an uncooperative town, and some bizarre twists and turns.

Of course, all of this is up for debate, because Virginia is a surreal adventure in the style of David Lynch’s work, with little that is outright explained. The events of the main plot, abstract dream sequences, and visions of the future all blur together, weaving a tale that’s rich in symbolism but light on answers. It’ll no doubt leave you scratching your head, but it also opens the game up to some fascinating interpretation.

Much of Virginia’s surrealism comes from expert use of cinematic techniques. Typically, when someone says a game is “cinematic”, they’re basically saying it has good production values – that it’s like playing a summer blockbuster. Virginia is cinematic in a more literal sense, in that it uses the language of cinema – editing, shot composition, score, and so on – to craft something compelling. Sudden, abrupt scene transitions are almost jarring, but they let each shot feed into the next, thematically and psychologically, in a way that you don’t often see in games. Indeed, with no dialogue of any sort, the cinematic work does the narrative heavy lifting.

To tell a captivating story without dialogue is a difficult task, and it’s easy to fall into the trap of coming across as vague just for the sake of it. But when it’s done well, speech-less storytelling can achieve things that a wordier script never could, and Virginia is proof of that. It’s a game that asks you to focus on the little details, from the subtleties of each character’s body language and props adorning each scene to the composition of a shot and the use of colour and sound. Without dialogue monopolising your attention, Virginia lets you you appreciate the visual and aural language that’s critical for understanding and appreciating the game.

On the topic of audio, Virginia’s soundtrack is phenomenal. Recorded live by the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra at the famed Smecky Studio, it has a rich, textured sound that works wonders for capturing and conveying the mood of a given scene. Crescendos and diminuendos are carefully intertwined with each shot to create an audiovisual spectacle that’s unlike any other in the videogame medium. It’s also just a great soundtrack to listen to in its own right.

All this talk about editing and film techniques may seem odd, given that Virginia is a game, but the way that the developers have, essentially, intertwined two very different mediums is part of what makes this game special. Make no mistake, this is a game, regardless of cries to the contrary from the “but is it a game though?” brigade. I don’t want to stray too far down the rabbit hole of trying to define what a videogame is, but I want to address some of the criticism that’s been flung Virginia’s way due to it not being “interactive enough.”

Virginia is a linear game, even by “walking simulator” standards. It has a story to tell, and as far as I can tell, there’s nothing you can do to influence its direction or outcomes. You can’t interact with the game world, in a mechanical sense, aside from those few objects that drive the story forward. You could watch a playthrough on YouTube, and to a large extent, you’d see and hear the same things as you would by playing it yourself.

But you wouldn’t feel the same things. At best, you’d get a watered down version of whatever the game’s trying to instill; at worst, you’d feel something completely different, or nothing at all. That’s because, as on-rails as it is, Virginia still requires the player’s input to drive the story forward, and that input is used to build a connection between the audience, the game, and the characters involved. You can’t influence Anne’s decisions, but you’re still responsible for what she does, and that makes you complicit. When she screws up, you screw up – it’s on you, even though it’s not your decision that led to that outcome. Even with a plot as prescribed as Virginia’s, having to actually press the buttons that drive it forward create an emotional connection that can’t be replicated by passively watching the same scene.

Moreover, the way Virginia intentionally restrains “interactivity” – in the sense of exerting your influence on the game – actually makes it more interactive, odd as that may sound. A lot of scenes simply move along and end when they’re meant to end, regardless of what you’re doing at the time. This is the height of mechanical non-interactivity, but it means that the choice of what you look at and focus on within those precious few seconds is all the more meaningful because you can’t see everything. And then, when you get to those scenes that do let you take everything in at your leisure, it’s like a breath of fresh air.

That’s what really makes Virginia work as well as it does: it uses the language of film to tell a fascinating story in a way that’s unusual for a videogame, but it also uses that language to subvert expectations about “interactivity” to create an experience that’s personal and subjective. Everyone will see and hear the same things, but how they interpret those cues and what they do with the limited interactivity will create an experience that’s uniquely theirs.

My one point of frustration with Virginia – and this seems like such a petty thing to bring up, but I found it more than a little distracting – is the frame rate. Noticeable jerkiness, especially when you’re trying to move the camera and focus your attention on a specific object, is a huge annoyance. For how much work put into building this engrossing work of art, it’s a real shame to let something as inconsequential as frame rate interfere with the experience, but here we are.

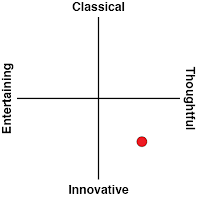

That little technical niggle aside, Virginia is a fantastic piece of interactive fiction, and a fantastic videogame. It’s rare to see a game that truly innovates on the way a story can be told through this medium, and to have something that doesn’t only push those boundaries but does so this effectively is a real treat.

– Matthew C.

Contributor