Review by Matt S.

For me, writing about games isn’t just about writing about games. It’s a calling. It’s an all-consuming passion. I started writing about video games right back when I had a Game Boy Advance and there was a site called GBACentral. I loved my GBA (it was a SNES in my pocket!) and because I wanted to get my love for the console out there in those heady pre-Twitter and Facebook days, I threw together an application to write reviews for the site.

They took me in. I was so happy. They even sent me “free” games. I was even more happy. Never did I let the fact that these games were free influence me, of course, but as a high school kid with no means to work a part time job, that influx of free stuff certainly helped fuel my passion.

Then I was at university, and suddenly, earning a bit of cash was an important thing. There was booze and… other things… to buy. I’d also moved over to a PlayStation 2 being my dominant console (Final Fantasy X!), and so I dropped an application over to Official PlayStation 2 magazine. They took me on as a freelancer, and then started feeding my Japanese RPGs to play. Probably because no one else wanted them, but that was a gap I was more than willing to fill.

I remember my first quote on the back of a box being for my review of Shin Megami Tensei: Lucifer’s Call (also known as Nocturne, depending on the region you’re in). Back in those days writing for a magazine meant that you’d only have about 300-400 words to play with, and anyone who’s read my reviews on DDNet would realise that’s an incredibly short review by my standards, but I did it, and I found myself quoted on the back of the box. That was the moment that I really felt that I’d made it as a games journalist, and, as I was finishing my last year of uni, I was pretty comfortable that I had a future ahead of me. The OPS2 scaled back, freelancers were the first to go, and I realised that the number of stable career jobs in games writing isn’t exactly something to bet a career on. Luckily games are related closely enough to other forms of technology that I was able to get a job as a tech business writer, and continue to cover the games industry through GamePro until I was ready to start up DDNet.

Through all this time my passion for games hasn’t really waned. I get tired, sure. I need breaks. I have other hobbies and interests that I pursue too. But I’ve never given up on games.

The reason for this long and rambling intro to my review of Superola and the Lost Burgers is, firstly, because I don’t actually want to talk about Superola and the Lost Burgers. But also, it’s such a miserable game that for the first time in a long time I’ve been left wishing that I wasn’t actually writing about games at all. It’s one thing for a game to be a terrible game and experience – such as Briks 2. It’s quite another for the game to be so aggressively cheap, tacky, and exploitative that it makes the entire games medium look bad in existing.

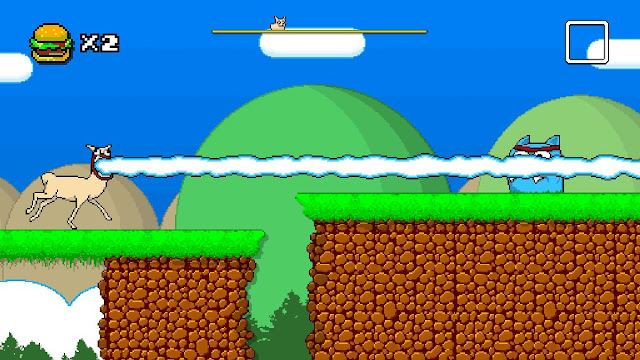

Superola is a runner platformer. You don’t control how your alpaca hero moves through the world. All you control is his ability to jump, and the ability to shoot lasers out his mouth every time he eats a burger. Putting logic aside, those lasers are useful in destroying everything that the alpaca would otherwise “die” in hitting, so the burgers are pretty important powerups.

The game plays terribly, though. Level design often has sections that would be impossible to get past without using a burger laser, which means any incentive that other runner platformers have in encouraging players to try and get through the level using pixel-perfect timing is gone. Just use the lasers at every halfway challenging spot and the overpowered nature of them will get you through everything.

The game as as aesthetically broken as I’ve ever seen in a game. Levels are generally “homages” to one franchise or another, but are universally done better in the ancient games they draw inspiration from. Original enemies look like they were drawn in a minute on Microsoft Paint, and are completely bereft of any artistic credibility. Many other enemies are copy/pasted directly from memes, and have no real reason for existing.

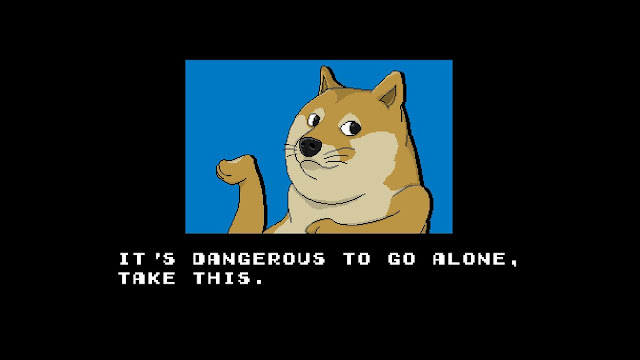

The plot – such that it is – also indulges in memes, many far too old to actually be amusing any longer. And breaking up the platforming are minigames, which are themselves borrowed from all kinds of random sources. Boss battles are a game of paper, scissors, rock, lizard, Spock (a reference to The Big Bang Theory, long gone from mainstream interest), and then a “bonus” game thrown in at regular intervals allows you to beat up cars, arcade cabinets, and so on, in a riff on Street Fighter 2’s popular minigame, only this time around it’s a simple rhythm game that you need to complete. Because reasons.

It’s one thing for a game to deliberately transgress the typical expectations of video games, to offer something highly surrealistic and “bad” by those standards, and yet hugely interesting to people like me who enjoy being challenged (not in terms of button presses, but in terms of thought), by the questions those games pose of game design. Daydreamer, a very… different and surrealist platformer from a few years ago, is the perfect example of that.

And then there’s just throwing a load of nonsense together because you liked old games and thought some memes were funny. There’s no insights on conversations to be derived out of Superola. It’s not a game developed by thinking developers to deliberately pull down the structures that hold games together. Superola is just a whole lot of nonsense that aspires to be a funny and entertaining game.

And it falls so short on both counts it’s an insult in existing at all. I’d rather castrate myself with a rusted spoon than think about this game any longer.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

|

| Please Support Me On Patreon!

|