Review by Harvard L.

Imagine being the last lifeline for someone kidnapped – you’re only in contact with them through text message, and you’re hanging on to every last message not knowing how things would play out. It’s a position of high responsibility mixed with tense anxiety, and that’s the clear setup made by Barcelona-based studio Appnormals Team. Its recent release, Stay, falls into the lines of many desk games such as Her Story or Secret Little Haven. It sees you parsing through a chat log and managing the emotional state of a kidnapped man, Quinn, as he tries to find out why and how he ended up in his predicament.

The bulk of the game will be spent in a chatroom interface, while reading Quinn’s messages and guiding him along his escape plan. The game starts with both the player and Quinn totally in the dark – you will need to work together to figure out exactly what kind of situation has unfolded, and to rationalise the potential dangers that Quinn must protect himself from. It blends elements of visual novel, text adventure and puzzle together to form a cohesive narrative, with high stakes and plenty of tension.

The mechanic which sold me most on this game was its constant timer: the time you spend away from the game is “remembered” by Quinn, and he will respond to your devotion or indifference in kind. At its best, it’s almost like having a person trapped inside your game console, or having to be responsible for someone in a difficult situation through constant text message support. It introduces the stress of the game’s thriller narrative into the real world, and creates a sense of empathy for Quinn, who begins to feel “real”.

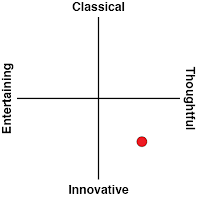

The game also provides a very complex interlocking system of bars and meters for the player to track Quinn’s mood and predict how he will react to each development. Quinn’s emotions are measured through four orbs representing the Four Temperaments – each corresponding to a personality type and a dominant responsive trait. The game doesn’t go to explain this interface at length (and it’s hard to imagine any software being able to trace the concentration of sanguine or melancholic emotions in any person), but I do feel like it’s used as a tool to clue the player in to how they should act, as well as to help the writers keep Quinn’s reactions consistent. The player is also able to view a trust graph and a measure of intimacy. If everything goes awry with Quinn and he loses faith in you, you’ll receive a non-standard game over where Quinn will cut connections with the computer, presumably resigning himself to a life in captivity.

Occasionally, you’ll be asked to make a choice regarding what Quinn should do next, at which you’ll receive an adventure-game-style ‘this choice will matter’ animation, and at the end of each chapter you’ll see how the majority of players chose in this instance. There are a swathe of endings to earn based on how you manage Quinn’s emotions and trust with you throughout the game, and these choices become instrumental in dictating how your relationship develops throughout the game.

Unfortunately, the choices are just as often a missed opportunity as they are a means to build empathy with the game’s main character. I found that, as each chapter needs a choice to tie it together, some of the earlier choices feel incredibly arbitrary and Quinn doesn’t really take what you say to heart. The choices themselves are also vague: you’ll be given a quick blurb of each one, but once you select it (and before you hit enter on the chatbox), you see what you – the player you – would type, and it’s occasionally not what you would expect from the blurb you were given. From there, Quinn’s reaction is similarly unpredictable. Some choices also don’t fit the game’s horror/thriller vibe at all, making light of Quinn’s situation or asking personality questions when the player character should really be more concerned about Quinn’s safety. It does build the sense that Quinn is a real person and not just a video game character obeying your whims, but it’s hard to feel immersed when ultimately the game reveals to the player how little control they have over the narrative.

Quinn himself also presents a problem to the player. He’s an unlikeable protagonist who is emotionally needy yet distrusting and distant, who carries his own set of problems before even getting himself kidnapped. At times, he directly states that he doesn’t see the purpose of being rescued – and that he views his predicament as a type of punishment for past misdeeds. The player often needs to prod him along to advance the plot, and you’ll fight against his own negative energy if you want to get anywhere. A lot of the game is also just watching him go about his actions. It plays into the theme of surveillance and voyeurism, and you could argue that the slow focus on the delicate pixel art fosters compassion, but it takes so long and achieves little.

The patchy character writing is exacerbated by the game’s insistence that it is “real”, with little insertions that end up ruining the suspension of disbelief and creating unintentional humour in what is intended to be a serious game. One interesting tic is that Quinn often makes typos as he speaks to you, fixing them up in the next message with an asterisk. This is interesting at first (and on a second playthrough it looks like the misspelt word is random each time), but it happens far too often and it makes messages scroll out slower than they need to. Similarly, Quinn’s dialogue changes tone all too frequently so that he can make a reference to a film or some other real-world fact, and it’s wildly inconsistent with how a kidnapped and imprisoned person should feel like.

Ultimately, this means that the game’s most interesting mechanic – the real time clock – falls to the wayside as well. With Quinn as neurotic and untrusting as he is, the game is unable to provide any real punishments for leaving him to his own devices – that is aside from the standard game over animation and starting you back again as if nothing ever happened. Despite all the empathy I felt towards Quinn at the start, the writers were never able to leverage these emotions against me, and after a while I stopped feeling responsible for his safety and rescue.

I think another detriment were the puzzles, which stopped all narrative momentum in order to force the player to look closely at some small details until their observational skills deemed them worthy enough to proceed. The puzzles are certainly very difficult! But Stay is not a puzzle game with a narrative holding it together, like The Talos Principle or The Witness. Instead, it’s a narrative game broken up by puzzles. If only there were an alternate version where you could either do the tedious and difficult puzzle yourself, or lett Quinn do it alone (and thus idle for a few hours real-time while he figures things out), the player would have an interesting choice which would feel impactful in the grand scope of the narrative. But with the way things are, Stay is filled with game over animations, long winded puzzles and questionable pacing which all too often robs the game of any gravity.

The artists at Appnormals do have a forte for pixel art which certainly shines through in their work. There is always a permanently animating headshot of Quinn in the top left to complement his messages, and it’s surprising how many unique animations and plot synchronisations that are managed in the game. The inclusion helps build a connection with the character that’s organic and real-time, and I don’t think any other type of art could have worked as well short of all out FMV from an exceptional actor.

In fact, I held onto the ride for longer than I had planned because the artwork was so gorgeous that I couldn’t wait to see where the game would take me next. For its escape-room premise, Stay’s narrative is surprisingly large in scope, and despite all its shortfalls the eerie atmosphere does linger with you as you play. It’s hard to deny that there are some incredible ideas at play here – and even if the execution is lacking in parts, the game’s sense of mystery kept drawing me in long after the puzzles and thriller plotline stopped being interesting.

– Harvard L.

Contributor