Review by Matt S.

I’m going to start this review with a personal comment: I don’t think there has ever been a game that is more difficult to review than Hideo Kojima’s ego sandbox… I mean Death Stranding. It’s a game where almost its entire worth is wrapped up within some truly incredible plot moments and spoilers, and naturally in the context of a review I don’t want to be spoiling things. That makes it hard to write about why the game is so incredible, though. What I can say to help give my opinion on the game context, is that I’ve never been a big fan of Kojima. That’s because I find that while his Metal Gear Solid series play well, the long-winded cut scenes and laboured metaphors and allegories that Kojima likes to throw into them, means they’re nowhere near as smart as he thinks they are.

This is why Death Stranding has amused and fascinated me so. It’s absolutely as smart as Kojima thinks it is. I’m now wondering if Metal Gear Solid really was Kojima bristling under the direction of Konami, because as his first project since his independence (and free of the control of the overlords), Death Stranding is just so much better as a piece of art than it is as a game. It’s like the balance has been flipped, and this is a Kojima I can really get on board with.

As I said, though, the problem with writing a review about Death Stranding is that it is impossible to talk about it to the depth that it deserves, without getting into the kind of spoiler territory that would get me into trouble with Sony and my entire readership. I’ll do my best to try and articulate the intelligent and poignant ideas that underpin the game (and promise that this review is spoiler-free), but if you do have questions, I’ll just say up front that many of the generalities I’ll be making will become crystalised for you as you play. With all of that out of the way, let’s talk about this remarkable – and unique – bit of big-budget artistry.

Death Stranding depicts humanity on the brink of collapse. After discovering – and leveraging – the afterlife (depicted as a “beach”), humanity has become beset by undead creatures, called BTs. The problem with these BTs is not so much that they’re out there to kill people (though they are). It’s much worse than that. If a BT latches onto a human, the clash of living and dead energies creates a small singularity – a voidout – which produces enough nuclear-strength energy to instantly wipe a city-sized section of the world out of existence, vaporising everyone caught within its blast.

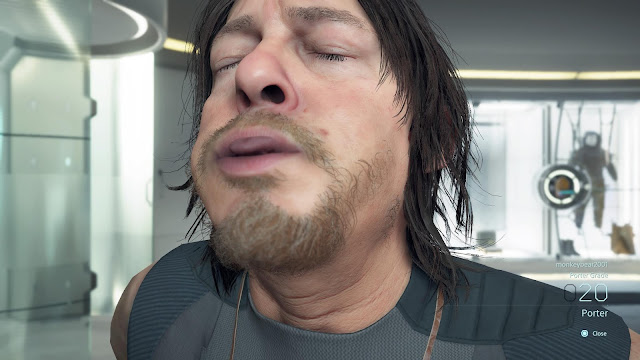

That is, except for Sam. Sam – played by Norman Reedus and his immaculately-shaped digital backside (which you’ll see a lot, and in great detail) – has a unique ability to be “rebirthed”, even if he’s caught in a BT blast. That in turn means that he’s relatively protected from the impending doom on the world, and uniquely suited to be a porter. A porter is a person that ventures out to carry goods across vast distances, from one settlement to another, while the residents of those settlements huddle inside, safe from the BTs.

With me so far? There’s one more important element to be aware of in this super-simplified summary of the narrative context; Sam and his glorious, frequently-bare backside, have a second reason for wandering from one huddle of humanity to another. Sam is also on a quest to save America by bringing people back together. There’s a kind of “Internet” that taps into the negative energy of the beach, and allows people to communicate and share materials safely across vast distances, without having to physically venture outside. They just need someone to come and connect them to the network in the first instance. Sam is therefore recruited by what remains of the American government to become a glorified tech hookup guy, and travel from place to place and getting them up and running on this network.

That’s just the concept of the game. It’s what Death Stranding does with all these narrative strands (hah) that makes the game so fascinating.

On the most simple level, the game can be read as a broad critique on the steadily shallowing nature of relationships in our increasingly hyper-connected world. Kojima’s clearly looked at the Internet and the superficial relationships that it fosters, and decided that the society-wide isolation that it is driving us towards is not good for us. Sam rarely meets or talks with people face-to-face. The cities that he visits are empty, soulless places – the implication being that its people stay indoors at all times. He makes his deliveries to warehouses, where he talks to the holographic projection of the people that he’s interacting with. He does this to earn “likes” – what passes for experience points in Death Stranding’s universe, and is explicitly modelled after the validation we all go chasing from our own activities on social media. Those rare moments that he does have the opportunity to physically interact with someone, we discover that Sam has a phobia of being touched.

Running around a hellscape teeming with floating dead monsters doesn’t faze him, but a handshake makes Sam recoil in terror. Putting aside the metaphoric implications of that, those rare moments where people do physically appear and interact with one another are also the moments where humanity is allowed to shine through, in the otherwise dying and miserable world. Most of these scenes are written horribly, and I wish Kojima had a better editor that was capable of pushing back against his occasional excesses, but the meaning behind these scenes is potent. For example, the first moment where you see two normal people interacting is when you need to physically carry one through a BT “zone” so she can get married to her distant, separated lover. It’s meant to be a powerful, emotive moment, and even if the delivery is clumsy, it is easy to understand the meaning behind that scene. Yes, Kojima is very much making a commentary on how physically detached we’ve become from one another.

More complex is Kojima’s commentary on broader American culture. This is more difficult to write about, because much of this commentary is locked behind the final few hours, and there’s just no way to unpack it without going heavy on the spoilers. Through much of the game the work that Sam does is under the auspices that it will “reconnect America” and recapture a very patriotic vision of what America is and means. For so (so) many hours the game plays this straight-faced and flat-toned and I – foolish me – did accept that the rhetoric was genuine. It’s not. It gets upended in the most shocking way imaginable as the revelations start coming in towards the end game, and as a social critique, Death Stranding hits on some truths and ideas that, you can only hope, will generate conversations about the American identity, culture, and how it both sees itself and its role in the world.

Beyond the socio-political stuff, Death Stranding is also a deeply philosophical game. The concept of the burden is a constant feature in Death Stranding. There’s not much “gameplay” in the game at all – Sam throws containers of stuff on his back, and then makes his way to wherever those containers need to be delivered – but the constant is that he is struggling under the weight of what he needs to carry, and that the work is unending. It’s very Sisyphean – as in, the ancient Greek story about a cruel king that was punished to spend eternity rolling a boulder up a hill, only for that boulder to roll back down to the bottom every time he got close to the top.

Sisyphus became a central story to the absurdists – a branch of philosophy closely associated with nihilism and existentialism, and maintained by philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard and Albert Camus, playwrights such as Samuel Beckett and Tom Stoppard, and so on. Absurdism holds that there’s no inherent meaning to the universe, and that while the individual can pursue meaning through life, death ultimately renders that pursuit meaningless. “This is because in reality there is no experience of death,” Camus once wrote in The Myth of Sisyphus. “Properly speaking, nothing has been experienced but what has been lived and made conscious. Here, it is barely possible to speak of the experience of others’ deaths. It is a substitute, an illusion, and it never quite convinces us. That melancholy convention cannot be persuasive.”

Death Stranding is Kojima’s attempt to grapple with absurdity, by asking the question “what if death can be experienced?” Far from subverting the view of the absurdists, however, Kojima’s musings instead seek to uphold it. Again, without giving away spoilers, what Sam (and by extension, you as the player) spend 50+ hours doing in playing Death Stranding ultimately becomes no different to Sisyphus almost getting to the top of that hill with his big, heavy rock.

The problem with all of this is that Kojima is a better thinker than he is storyteller. Much of Death Stranding is made overly complex and with half-developed side musings that don’t end up adding much to the experience. At points I almost thought that Kojima was looking to bring across some commentary about religion, with Sam’s burdens behaving, at points, very much like the Pilgrim’s burden from the classic Christian novel by John Bunyan. Not much comes of this. At other times Kojima goes on long, and largely unnecessary explanations to try and create a scientific defence for what’s going on (Death Stranding fails miserably as science fiction), and the “rebirthing” mechanic and the use of the babies-in-bottles is underbaked, and almost seems like it was thrown in there more as an attempt to be “surreal” than to use it to further the narrative’s themes. Death Stranding is a big, complex project, and it does feel like it got away from Kojima at times. That doesn’t mean that it’s unworthy, but rather a sign that the video game industry is still maturing as an artistic medium, and it’s by no means easy to sustain core themes and intent across a 50+ hour-long experience.

What Death Stranding absolute nails is the atmosphere. Many players will find this game dull; Sam’s carrying so much weight that he doesn’t tend to make his way around the massive world quickly, and while there’s the rare moment of tension and action from those damn BTs (that you need to either sneak past, or can later use weapons against), for the most part it’s a very lonely, long journey. It’s dirge-like, in other words, and the musical tradition of the dirge is appropriate to a game that, itself, is one of mourning and frequent grief. Every so often as you explore, the camera will pan back and a sorrowful bit of music will kick in from the stunningly melancholic soundtrack. There’s dour beauty in that, and it never stops being beautiful, even 50-hours in.

Given the recurring themes of loneliness and isolation, it might at first seem like the asynchronous multiplayer elements are at odds with Death Stranding’s themes, but, much like as with From Software’s Souls games those elements, if anything, enhance the loneliness. At points it’s possible to work with others to contribute resources that rebuild highways devastated by the BT’s destruction, build bridges across rivers and ravines, or create shortcuts across mountains by putting up some ladders and ropes. Those elements will then be dropped into other player’s games, and if they make use of them, you’ll get additional “likes”. Coming across a lonely bridge in the middle of kilometres of blasted landscape is both a relief (because deep rivers are a threat in Death Stranding), but the lack of a visible, present community around that bridge only deepens the sense of isolation from meaningful contact.

When Kojima isn’t trying quite too hard, Death Stranding is also an incredible work of visionary art direction. There are moments where things get overcooked and ridiculous, but when the game is on song, it is mesmerising. My favourite moments were actually when the BTs grab Sam. When that happens, he loses all the cargo he was carrying around, and the BTs will drag him some distance as the world around him starts to look like it’s covered in ink, with reversing gravity to boot. Then you’ll see a ink whale leaping out of the muck, and you’ll know that Sam is in great danger – those things are direct from the beach, and unless you can struggle your way through the muck and get away from the beasts, it’s voidout time. Thankfully I never had a voidout this way (I assume it’s a game over), but the desperate effort to escape is one of the most intense experiences I’ve had in a video game, and that’s entirely because the art direction behind it is so breathtakingly intense and intimidating that it had me fully invested in what is going on.

The main character performances are uniformly great as well. He seems like he has an ego the size of a voidout, which is never easy to work with, but Kojima does have a knack for getting the very best people on his projects, and the talent he got on board for Death Stranding is really above and beyond. Norman Reedus is more than a perfectly-shaped backside, and Mads Mikkelsen is so likable in his very sympathetic role. He stars in a series of visions that Sam experiences, and while it would be, again, spoilers to say more than that, what initially seems to be of tangential importance to the “real-world” action becomes a critical part of the narrative towards the end game.

The real scene-stealer, however, is Troy Baker, who plays a gleefully self-aware villain, going as far as to call himself the “end boss,” and speaking directly to the audience when, after the particularly slow first 15 hours opening chapter, he shows up, saying words to the effect of “isn’t this what you’ve been waiting for? A game over?” It’s a challenge – not to Sam, but rather to the player, daring them to have the “but this is a walking simulator!” reaction that Kojima surely knows is coming from some players. There are other elements of truly oddball or wry humour scattered throughout Death Stranding – including a rather delightful moment where an apocalyptic cosplayer gives you an otter cap – and this is perhaps the one area where Kojima shows restraint. Death Stranding would have been miserable without some relief from the dirge-like energy, but too much humour and self-aware winking would have ruined his carefully-tuned atmosphere. He has nailed the balance there.

Death Stranding does belong in an art gallery more than it does sitting on consoles next to more traditional “games”. As I sit here to write this, I am fully convinced that there are going to be plenty of reviews from my peers that veer to the other extreme with their scores. And fair enough, because as a “game” Death Stranding doesn’t do much. But as a work of art, Death Stranding is something mesmerising, intelligent, and powerful, and we never see genuine art within the big budget, blockbuster space. That alone makes it a rare treat to play, and I rather like this new-look, independent Kojima.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld