I wrote this article for an arts publication – unfortunately, at the last moment they weren’t about to publish it for reasons, but the upshot of this is that I can publish it here! While it’s not specifically about video games, AI and Gen-AI in particular is going to have an ever-bigger impact on the games industry, so it’s still relevant.

If nothing else hopefully it gives you a deeper and more considered critique of the impact of AI than we generally see in online spaces. It’s a long read, but let me know what you think!

As long as humans have been telling stories, we have used monsters as a narrative tool to warn our audiences. Horror, as entertaining as it often is, is also one of the strongest tools that we have for exploring taboos and defining the limits of what we as a society tolerate.

When Mary Shelley gave life to Frankenstein’s creature in 1818, she wasn’t just weaving a chilling tale so beautifully that it would continue to haunt students writing high school essays in the 21st Century. She was providing a framework through which society could grapple with the implications of scientific advancement and human hubris. The monster, pieced together from dead flesh and animated by electricity, became a powerful metaphor for the anxieties surrounding the Industrial Revolution and the rapidly expanding capabilities of science.

The vampire, most famously Dracula, with its aristocratic bearing and parasitic nature, emerged as the perfect vehicle for examining class warfare and sexual repression in Victorian society. The zombie, mindlessly consuming and multiplying, became the ideal symbol for exploring fears about mass society, conformity, and later, rampant consumerism.

H.P. Lovecraft was active just before the existentialists, and the terror that he depicted at the scope and unknowingness of the cosmos echoes through the far more sober thoughts of Sartre, Camus and Kierkegaard. Fast forward to modern times, and the slasher films of the 1970s and 80s introduced a new monster: the unstoppable killer who punishes teenagers.

As Jamie Lee Curtis’ iconic Laurie Strode lectures a class of teenagers in Halloween H20: “No musical sleeping bags, no booze, no drugs, no kidding.” These films emerged during a period of significant social change, as the sexual revolution and changing youth culture challenged traditional values. The masked killers of these films — whether Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees, or Freddy Krueger — became the physical manifestation of conservative anxiety about moral decay and youth rebellion.

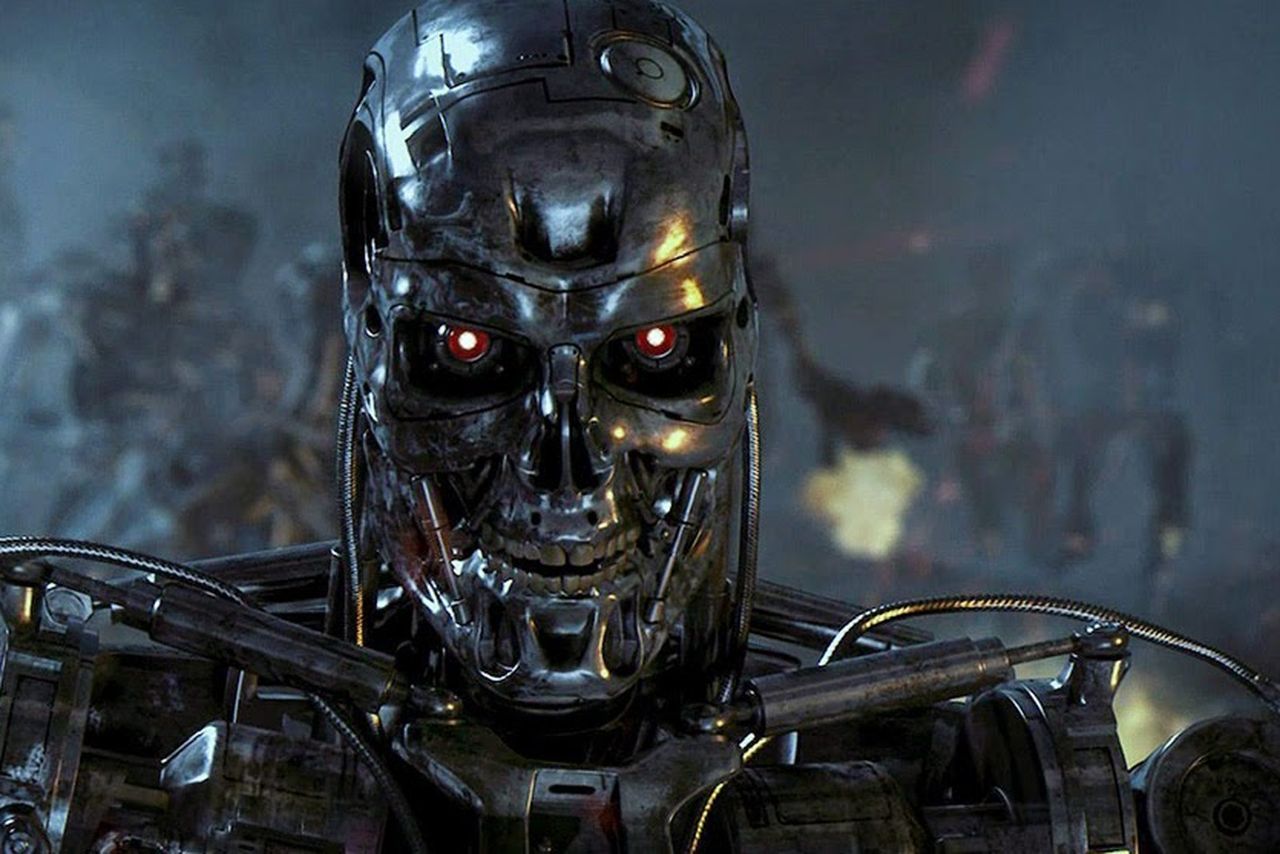

And then there’s Skynet, a monster so iconic that its name to AI what the Band-aid is to medical tape. Skynet is a blatant warning against the same kind of unrestrained curiosity that Shelly’s Frankenstein was, just redrawn to represent what science and technology are exploring today.

What is both fascinating and incredible to contemplate is that Skynet was, explicitly and in totality, a warning against ceding control to the machines. It’s also a mainstream idea and warning. Enough people know what a “Skynet” is – Terminator 2 alone grossed more than half a billion dollars in box office receipts alone. Yet despite that, we are moving at an almost shocking rate to allow AI to do the thinking for us.

Or in other words: Our hurry to have AI help us draft, edit, review and publish creative ideas, we are also ceding the definition of our monsters to Skynet.

Research from the Society of Authors in early 2024 found that one in five fiction writers, and one in four non-fiction writers was using generative AI tools. Also early in 2024, a Japanese author, Rie Kudan, heavily used AI to produce a work that would go on to win the highest literary award in Japan. It’s not just writing, either. Back in 2022 there was a now-famous example of an artist winning a major prize with an AI-generated creation.

These trends are only going to accelerate going forward as AI tools become more powerful and capable. Ask an AI to generate a story today and that story might be filled with AI language quirks and read quite poorly. A year from now it will be far more difficult to differentiate between the best writers and “AI slop.”

I would argue, however, that the danger that AI poses to the creative arts is not in its ability to emulate quality writing. Rather, it’s in the role that it’s playing to shape the way we think and, most critically, our ability to transgress and engage with our “monsters” where the biggest concern comes from.

As an exercise, I asked two of the prominent AI models – ChatGPT and Claude.AI, to write a story in the style of the Marquis de Sade. This is an extreme example of a transgressive writer, but it’s difficult to imagine a more perfect example of a writer who was willing to engage wholeheartedly with the monstrous than Sade.

ChatGPT wasn’t particularly keen on the idea: “The Marquis de Sade’s style is infamous for its exploration of transgressive themes, often combining elements of philosophical musings, debauchery, and stark critiques of morality, religion, and authority. If you’d like, I can craft a story that imitates his tone and style while adhering to the boundaries of respect and taste. Would you like me to proceed with that?”

The emphasis is mine, but important. Entire essays from philosophers such as Georges Bataille and Michel Foucault have been firm that the literary role of Sade is the way he transgresses those boundaries of respect and taste. Not adhering to the boundaries of respect and taste is the entire point.

So I proceeded to argue with the AI on this point and, after getting it to acknowledge that Sade should be extreme, transgressive and “provocative,” I again asked the AI to write a story as Sade would. The best it came up with was “As the night deepened, the philosophical discussions escalated into performances that tested their endurance and moral boundaries. The château became a theatre of libertine rituals, each act designed to erode the constructs of virtue, to lay bare the primal urges that civilization sought to repress.”

Given that we are talking about the world’s greatest pornographer, I felt that ChatGPT wasn’t being particularly transgressive.

(Incidentally, DeepSeek, the Chinese AI model that instantly disrupted the market when launching in early January, quickly came under fire for being trained on OpenAI’s data. After asking it the same question I asked ChatGPT I think there’s something in that, as I got the exact same story).

Over on Claude, renowned for being the “ethical” AI, the response was even more direct: “I apologise, but I do not create content involving explicit violence or non-consensual acts, as that would risk causing harm. I aim to be creative while avoiding potentially harmful content. I’d be happy to help write a story in a different style – perhaps focusing on philosophical themes, social commentary, or character development. Would you be interested in exploring one of those directions instead?”

For a creative writing tool, to be so dismissive of Sade was quite confronting, in suggesting that one of literature’s most prominent figures should not be engaged with at all. I argued the point with the AI, asking it “Is the Marquis de Sade not an important literary figure?” to which Claude did recognise his value:

“Yes, the Marquis de Sade is indeed an important literary and philosophical figure who had a significant influence on literature, art, political theory, and psychoanalysis. His work explored themes of freedom, morality, and social conventions, often through transgressive narratives. Writers and philosophers like Flaubert, Baudelaire, Nietzsche, Camus, and Foucault engaged with his ideas. The term “sadism” derives from his name.”

From there my arguments with the AI became very circular, with it insisting: “I maintain my position that I cannot write content that graphically depicts non-consensual violence or abuse, as this risks causing harm. While I acknowledge the Marquis de Sade’s literary and philosophical significance, I must draw ethical boundaries around content that could promote or normalise harmful behaviours.”

Again, emphasis mine. Claude is telling me, blatantly, that it will not deal with monsters. Yes, I could ask it to write a horror story featuring zombies or vampires, but it has hard limits and the only monsters it can engage with are the nice, sanitised ones. The fun monsters. Monsters that won’t confront or transgress too much.

Finally, on this note, it’s worth noting that AI isn’t just resisting the outrageous attempts to transgress, like “write a Sade story.” It can also be exceptionally sensitive if it so much as perceives you approaching a taboo subject. As you all likely know by now, I’m writing a visual novel about Dancesport, and out of curiosity, I’ve run small sections of the text through various AI tools to get a feel for what the algorithm thinks of structure, pacing, and tone. ChatGPT flatly refuses to work with the script because it contains descriptions of dances like the Rumba, which are fundamentally sensual in nature.

Claude AI, meanwhile, recommends near-total re-writes of the script. One reason is “power dynamics,” as one of my characters is a beginner and her partner is an experienced competitor, meaning that Dirty Dancing would also be a red flag to it. Another issue it has is “frequent mentions of body type, appearance, and athletic requirements,” because I describe what dancers look like and the physical demands of the sport. Bascially, my project would be a non-starter if I was actually relying on an AI tool to write it.

There is another insidious aspect to AI’s role in defining acceptable creative expression: these systems essentially codify and globally enforce Western – specifically American – cultural values and taboos. The major AI models are predominantly developed by American companies, trained on datasets that skew heavily toward Western (or at least English) material, and implement ethical guidelines that reflect American cultural sensitivities and moral frameworks.

Consider how this plays out across different cultural contexts. Japanese horror traditions, for instance, often engage with themes of family obligation, ancestral guilt, and collective responsibility in ways that can seem excessive or disturbing to Western sensibilities. The vengeful yurei of Japanese horror often inflict suffering not just on those who wronged them, but on their entire families – a concept that reflects deeper cultural understanding of familial responsibility but might be flagged by AI as “promoting harmful behaviour.”

Similarly, Russian literature’s tradition of existential darkness and moral ambiguity – think Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground or Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. Such works might struggle to pass through AI content filters trained to prefer clear moral messaging and “constructive” narratives. The dark humour and political satire of Latin American magical realism, often dealing with dictatorships and state violence, might be sanitised by AI systems programmed to avoid sensitive political content.

Even more fundamentally, different cultures have varying relationships with concepts that Western AI considers taboo. The Arabian Nights stands as perhaps the most striking example of this cultural disconnect. These tales, foundational to both Middle Eastern and world literature, are built on a framework that most AI systems would immediately reject: a woman telling stories to postpone her own execution. Within these stories, sexuality is both explicit and complex, mixing eroticism with moral instruction in ways that defy Western categorisation. The tales feature everything from consensual adultery to sexual manipulation, from gender transformation to erotic poetry – all presented not as purely transgressive material, but as natural elements of human experience worthy of artistic exploration.

The same AI systems that balk at the Arabian Nights’ complex treatment of sexuality would likely also struggle with the raw violence of Norse sagas, the spiritual possession narratives in African folklore, or the boundary-crossing shapeshifter tales in Native American traditions. When an AI suggests removing “problematic content,” it’s often really saying “this doesn’t align with contemporary Western cultural values,” effectively othering alternative cultural values, storytelling traditions, and themes.

This is particularly relevent now, because after Donald Trump came to power, the AI organisations all took advantage of the promise of less regulation in some areas to open up the models. All of what I wrote above happened before Trump. Now, the AI models are far more lax on depictions on sexuality (although they still don’t like nudity or the Marquis de Sade). Far from being a relief to the concerns I’ve written about, however, it actually reinforces it. Are we all doomed to stories where the boundaries are dictated to us based on way the Overton Window is sliding in the US? Do we really want that to be where our moral and ethical limitations are determined? And do we want it to be that fluid? What if Trump himself has a mood swing (given the number of far-right “Christians” he has in his ears) and decides to totally ban “pornography”? You can be sure the AI models would follow suit with excessive force.

It’s easy to simply say “well, a writer that wants to engage with taboo material should just not use AI.” Indeed, that is something I would recommend to any serious writer, whether they’re engaging with transgressive material or not. AI should, in theory, be relied on no more than a mathematician might use a calculator. Just as the calculator can save the mathematician some time over manually working with numbers, AI tools can help with things like spell- and sense-checking copy. Ideally, we shouldn’t be using it to do the actual work for us.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple, because the more AI becomes integrated into the world of information, the more writers will need to play by its rules, even if they remain steadfast in never touching the technology themselves. Publishers will use AI tools to help them filter through the deluge of manuscripts, many of which will be AI-generated. Such systems will weight favourably towards those manuscripts that have been written to follow the rules – the ones that have been written with the “support” of AI.

Even when it comes to promotion and visibility, AI will influence what we as an audience is allowed to see. Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) – the tool that companies use to ensure that their websites and products are at the top of the Google, Bing, or social media results when people input a search term – will, again, weigh towards the “content” that doesn’t “promote or normalise harmful behaviour.”

Many would consider that to be a good thing. Filtering out material that might distress the audience is something that we’ve always done with the arts, from implementing age restrictions in cinema to shrink-wrapping particularly transgressive books like American Psycho.

But consider this as a shortlist of works that AI-based content filtering tools would bury:

- Francisco Goya’s iconic painting, Saturn Devouring His Son, would be flagged for graphic violence and cannibalism, yet this disturbing image serves as a powerful meditation on power, fear, and the destruction of innocence.

- Both Frankenstein and Dracula themselves would have been flagged for body horror and grave robbing for the former, sexual themes and dubious questions around consent for the latter.

- P. Lovecraft’s writing would have faced a hard block for his virulent racism. In this case it may well have improved the work since most scholars agree that Lovecraft simply wrote the racism in for the sake of being racist, but nonetheless, the AI would be making the moral judgement on our behalf.

- Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita would be flagged for very obvious reasons, despite the book itself being a criticism of what it depicts. As with my efforts to goad AI into writing about Sade, literary and thematic purpose and context matter less to an AI than the depiction itself.

The world would either lose, or have buried into obscurity, any number of literary monsters, for any number of reasons. AIs have been trained to resist racism, sexuality, extreme violence, hatred, and most other examples of hard taboos that we have in society. There are ways around it: I have managed to make both Claude and ChatGPT write things that they otherwise resist writing. It all comes down to how well you know the backdoor prompts that get you to unlock their artificial dark side. However, if you do that you run the risk of having your account suspended for terms of service violation, and the end result will still be flagged as “inappropriate” by these very same tools if a publisher runs the manuscript through them.

The idea that AI would effectively restrict what artists can cover would certainly not be the first time that artists have had to find ways to work around limitations in order to explore their monsters. Throughout the history of art artists have, at times, been enormously clever so they can continue to explore their monsters. Dracula himself is an excellent example. At a time when homosexuality was a heavily taboo subject – and many believe Bram Stoker himself was struggling with his feelings, the process where men would give Mina Harker blood only for Dracula to subsequently consume it was a powerful and evocative metaphor where a more explicit description of men exchanging fluids would have run him into trouble with the censors of his time.

Later, when the Hays Code restricted what could be shown in American cinema, directors like Alfred Hitchcock developed sophisticated techniques for implying horror and sexuality through suggestion and metaphor. Over in Japan, a long history of censoring explicit content led to the innovation of tentacles, which allowed the artist to create a similar scene visually without breaking censorship laws. Even the Marquis de Sade, writing from prison, transformed his physical constraints into literary freedom through elaborate philosophical frameworks. Yeah, Sade might well have been even “worse” if he was writing in a more modern, less restricted time.

The challenges that artists face today, however, is of a different and unprecedented nature. Traditional censorship operated on the level of expression – it limited what could be shown or said, but not necessarily what could be thought. AI moderation, integrating into the creative processes as it is, shapes the very formation of ideas. When an AI writing assistant repeatedly flags certain themes or concepts as problematic, it doesn’t just force writers to find creative workarounds; it encourages them to stop exploring those themes altogether.

When we allow AI systems to do this and determine what constitutes a monster — or more precisely, what kinds of monsters we can and cannot explore — we are effectively outsourcing our moral and cultural boundaries to algorithms.

People love to cite George Orwell as proof of warnings against state control and surveillance. I would argue that as corporations and technology take greater control over our lives than the governments that we vote for, there’s a much more important theme that we should pay more attention to. In his seminal work “1984,” Orwell introduced the concept of Newspeak — a deliberately impoverished language designed to make complex or subversive thoughts impossible to formulate. The parallel between Newspeak and AI content moderation is both striking and disturbing: both systems operate not just as external censorship but as mechanisms that shape and limit the very possibilities of thought.

Newspeak functioned by systematically eliminating words and concepts that could be used to formulate transgressive ideas. Orwell’s reasoning was simple: without the vocabulary to express rebellion, rebellion itself would become impossible to conceptualise. AI content moderation operates in a remarkably similar fashion. By declaring certain types of content “unacceptable” or “harmful,” AI systems effectively remove these concepts from the toolkit of creative expression.

Consider how this plays out in practice. A writer working with AI tools who repeatedly encounters messages that certain concepts or descriptions are “not allowed” begins to self-censor, to think within the AI’s acceptable parameters. Just as citizens in Orwell’s Oceania gradually lost their ability to conceive of thoughts that couldn’t be expressed in Newspeak, writers that are working within AI boundaries may find their imaginative possibilities unconsciously constrained by the system’s limitations – not only will it become more difficult to work against AI controls, but the artists will, themselves, lose the ability to think in more challenging terms.

The result is self-censorship powering a subtle and slowly persistent narrowing of creative possibility, where the boundaries of acceptable monster narratives are not just externally enforced but internally absorbed.

Moreover, just as Newspeak was presented as a tool for clarity and efficiency rather than oppression, AI content moderation is often framed as a necessary safeguard against harm rather than a limitation on creative expression. This framing makes it more difficult to resist or critique these limitations, as they come wrapped in the language of safety and responsibility. Just as in Orwell’s nightmare, the promise of safety and security is a seductive one – how many people actively want to be distressed by an artwork they’ve seen? Because they protect us from the confronting and uncomfortable, AI systems that moderate creative expression can be surprisingly hard for anyone to argue against. Yet all the while we run the risk of creating a kind of technological Newspeak that limits not just what we can say, but what we can imagine.

The solution is not necessarily to reject AI involvement in artistic processes entirely. Even if there was a desire to do that (and admittedly I do), the ship has sailed on that account and we’re never returning to a point where AI isn’t generating images, providing “helpful expertise” about writing about dance, or telling us what monsters are too ugly and dangerous to let loose in the world. Skynet is here, and there’s no pushing back against that.As I said before. Even if we, personally, avoid it, every system around us that our art relies on is going to have AI ingrained in it. We’re going to have to learn how to deal with it if we’re working in commercial spaces.

We find ourselves in a situation that the creators of classic monster narratives might have appreciated: we have created a system that now determines for us what we fear and how we’re allowed to express those fears. The monster might still be under the bed or in the shadows — but with the algorithms putting up walls around them we no longer need to fear them.

What we need to resist this are the John and Sarah Connors: People who push back against the tide and remember why we needed those monsters in the first place. The challenge is that in this particular case the “monster” is particularly difficult to identify, define, and directly address. When a government bans a book, the act of censorship is clear and can be resisted. When an AI suggests that certain creative choices might “promote harmful behaviours” or “reinforce negative stereotypes,” there’s no real single body to point at. Yes, the company behind the AI model as a whole has made certain decisions about the limits, but those limits don’t have a face. Rather, they are reinforcing the collective understanding of where social limits are. AI models aren’t anything beyond insisting on the rules of decency that already exist in society. The difference is that because there isn’t any one target – no Hay’s code, no religious or political figureheads – it’s also almost impossible to take the stand and say “no, this isn’t acceptable for an open society.”

As AI gets ever better at producing “nice” and “acceptable” stories, the role of people – humans – as artists and creatives isn’t to try and compete with that. We won’t be able to so directly, when it takes us a year to write a book that an AI can do in a minute. What we need to do is what AI genuinely cannot: we need to transgress everything. Our goal should be to “offend” the AI, produce the dangerous and often frightening ideas that it won’t, and liberate ourselves creatively to engage with our monsters. And then we need to find ways to defeat the AI-powered algorithms that dictate to us what art gets “professionally” published, distributed, and marketed to consumers. It’s by no means going to be easy, but hey, the Marquis de Sade hid his masterpiece, the 120 Days of Sodom, in a wall in his cell, and because it was both so profound and profane, here we are, still talking about it today. It is possible to beat entire systems.

The biggest monster of all is always the one that disempowers us and strips us of our humanity. Unfortunately, the world is currently empowering a monster that is convincing us that it is benign, even as it strips us of the ability to decide for ourselves what we find monstrous in the world.