Shinto is one of those things that most people who know anything about Japan have some vague concept of, but don’t really know anything about. From experience, they’re also rarely interested and that’s depressing. Tourists in Japan do cheerfully visit Shinto shrines, before mistaking them for Buddhist temples (and vice versa), and spending more time taking awesome Instagram photos than taking the time to try and learn anything about the country’s native religion. But who knows? Perhaps Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess will be different. Perhaps the people that play this game will see it as more than aesthetics and a bit of fun, and after playing it they will be inspired to go and learn something about it.

Or perhaps not. For the overwhelming majority, gaming is all about shallow consumption and not the experience, after all.

Anyhow, putting my bitterness aside for a moment, Kunitsu-Gami is designed to be an experience rather than something to be consumed. The core motif in Kunitsu-Gami is that of Kagura dance. Kagura is a real thing, and a type of ritual that is predominantly performed by women, through which she becomes a soothing and/or entertaining presence to the kami (Gods) around her, and in performing that service she acts to pacify and protect the area.

This is an ancient form of dance, and while it is a “living performance” in that Kagura traditions do change over time and what we see today is nothing like the dance in other eras, it is considered to be one of the oldest continuous forms of performance in Japan’s very long history. The origins of the dance are, indeed, traced right back to one of the origin stories featuring Shinto’s supreme deity, Amaterasu. In that story the goddess was angered, and she hid herself into a heavenly cave. As Amaterasu is the sun god, doing so plunged the world into darkness, and after much effort to make her come back out, it was eventually another God, Ame-no-uzume, who was able to compel Amaterasu to emerge again by performing a lewd (though Kagura dances aren’t that any more) and comical dance that caused all the other gods to laugh. On hearing the laughter Amaterasu became curious enough to see what was going on, and so she left the cave and sunlight was returned.

Today there are many forms of Kagura dance, but the common thread between them is that they are a central and critically important ritual to Japanese spirituality. As noted in Performing Power, an essay on the impact and importance of the dance form: “The kagura performance itself is this liminal phase. It creates it by first establishing the boundary between human and kami, and then proceeding to abolish it (Gilday 1990: 265-271). (It is, again, a binary conceptual structure which is being fused.) This boundary-blurring or fusion of worlds is a characteristic of this kagura. Both the human and divine realms derive their life energies from this meeting point of the realms, their fusion point, the point of power.”

Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess is, in every way, an embodiment of the power and role of Kagura. You play as a guardian spirit (a figure that represents the broken boundary between human and kami) who needs to protect a Shrine Maiden as she purifies a sacred mountain from hordes of invading evil spirits. In addition to his own (beautifully graceful) movements, the guardian is also able to compel living humans around him to take up roles and aid in the Shine Maiden’s defence. This is a fairly laboured but effective symbol of the power that the religion holds over people.

Mechanically, Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess is a very standard tower defence experience. The guardian spirit is able to rescue and then recruit townsfolk humans and then give them martial jobs to pitch into the defence of the maiden. The humans act as the “towers”, though they’re not static and can be commanded around to set up defensive lines on the many paths that the enemy spirits can take to attack the Shrine Maiden. Meanwhile, the guardian spirit is free to move around and can fight himself, as is standard for the “big budget” tower defence titles like Orcs Must Die or Dungeon Defenders. While this formula isn’t in any way revolutionary, what Kunitsu-Gami does do very well is keep the variety strong from level to level. There are some levels where some wild environmental effects act to disrupt your strategy, and then there are times were you’re unable to do any direct fighting and so need to rely purely on your ability to move your “towers” around.

However, the strategy side of Kunitsu-Gami also never becomes overly stressful or taxing, and that befits the Kagura theme, too. It’s not meant to be an intense, challenging experience to watch. Within the game, as long as you work efficiently you have plenty of time to get everything done that you need to during the “day” hours so that when the enemies attack at “night” you’re prepared. There are plenty of resources available to make sure that you can follow through with your preferred strategy, and in direct combat the guardian spirit is more than effective at holding his own. It’s strategic, but not stressful.

What does become somewhat more intense is the boss battles, where the Capcom Monster Hunter heritage comes to the fore. Rather than being an inelegant toe-to-toe throwdown, however, the boss battles challenge you to make effective use of the townsfolk warriors in a way that reminded me most keenly of Little King’s Story (remember that delightful gem?).

Most superficially, but also quite critically, Kunitsu-Gami is utterly gorgeous. The subtle, dance-like movements of both the guardian spirit and the Shrine Maiden help to carry a narrative that is very thin on direct conversations and cut scenes, but effective at visually telling the story of Kagura. Meanwhile, the enemies are of a hellish creativity, but it’s Yomi hell rather than Christian hell. The Japanese underworld is a distinctly different thing so has a totally different aesthetic.

In terms of the art direction, you can tell that this came from the same place as Monster Hunter, but given the eye for detail among those artists, that is not a negative at all. It is unfortunate that you spend so much time with the camera scaled back as far as possible so you can get a good view of everything. The detail in the art direction deserved better than that, but still, it’s absorbing at all times.

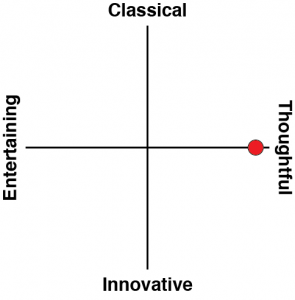

It’s a little annoying that so many people will play Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess and not then take it upon themselves to learn something about where the game comes from. To suggest it’s an “action tower defence” game is doing it a disservice. No. Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess uses the action tower defence mechanical framework to share something an authentic and meaningful interpretation of Kagura through the video game medium. Capcom previously did something similar with Okami, only to have people limit it to a “Zelda clone.” But just as Okami had something sincere to say about Japanese spirituality, so too does this game. Hopefully, at least some players are inspired to learn where this game comes from.