Kashido is one of the more interesting, downright fascinating board games I’ve played in recent years. It comes to us from Japan, and is an abstraction of a significant and cultural part of Japanese food culture. It is a physical board game in Japan, but as far as I can tell this is the first time the rules have been translated into English. It is gorgeous and a total joy to play… but somehow the developers overlooked (or weren’t able to implement) one critical feature and that renders the entire purchase totally pointless.

The game is an abstraction of wagashi. You have probably seen images of wagashi, even if you’re unfamiliar with the word or have tried some yourself. We’ve all seen the intricate, delicate designs that Japanese sweet-making artisans come up with, using traditional plant-based ingredients like mochi, anko, and fruit. Wagashi are little works of art, and are traditionally served with green tea at places that trade in Japanese tradition. You don’t really see these in Japanese supermarkets, in other words, but they are a treat that you’ll enjoy if you ever find yourself at a ryokan.

Wagashi is popular as much for its aesthetics as its taste, and is analogous to the works of the finest chocolatiers or patisserie chefs out of France and Belgium, where presentation and aesthetics are as core to the experience of eating one as the taste. Indeed, on a personal note, I find these sweets a little difficult on the palate (all these years of travelling to Japan and I haven’t quite come to terms with red bean and mochi as a combined flavour). But I’m fascinated by the craft and skill that go into preparing each one, and I could look at them all day long.

Kashido, in a very abstract sense, tells the story of four of these craftspeople vying for the right to make wagashi for their lord. But, to be very clear about this, it’s every bit as abstract in its depiction of both the sweets and the purpose of the game as chess is the abstraction of battlefield tactics.

Unfortunately, the rules are a little poorly translated (it’s readable but not necessarily the best way to explain the game), so it’s going to take some patience and trial-and-error in the early stages to properly understand the flow of play.

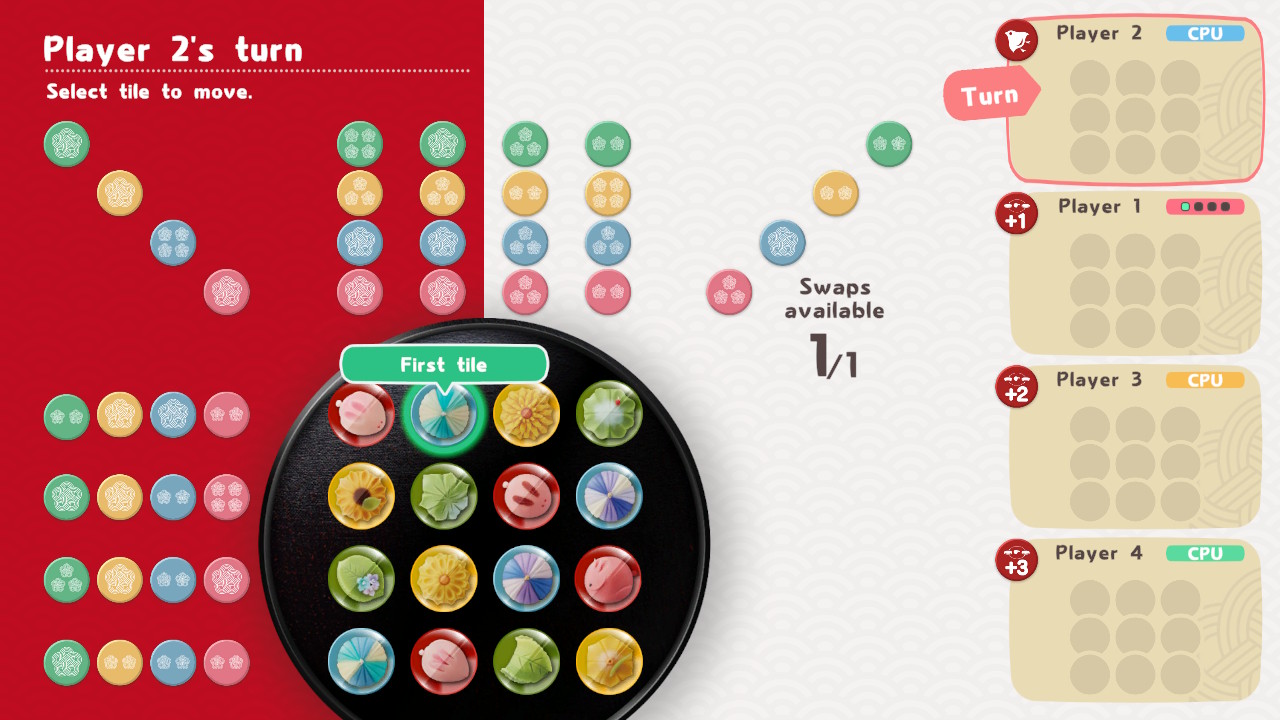

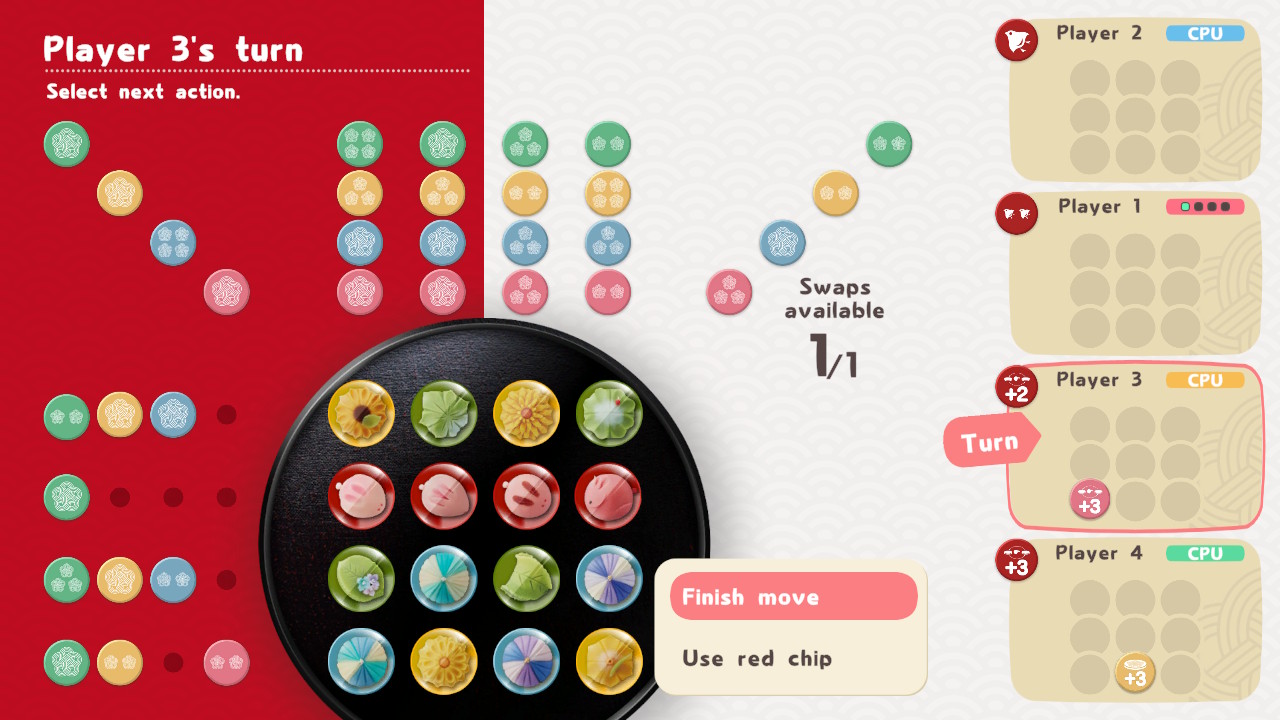

Basically (and perhaps I can do enough to explain it in my review), there’s a grid of little gemstones of four different colours in the middle of the playfield 4×4 in size. For each row, column, and diagonal, there are four tokens, each of which have a token that is one of those four colours, and has a number printed on it. On your turn, you move one of the little gemstones to swap it with an adjacent one, as though you’re playing a match-3 game. At the end of your movement, you can take one of the tokens, as long as that token has the same number of coloured gems in its row, column, or diagonal as is printed on the token.

So, if the second row has tokens that say “1 red,” “2 yellow,” “3 blue” and “4 green,” and in that row there were two blue and two red gems, then you could take the “1 red” token, or you could move another blue into the row to take the “three blue” token. Naturally the higher the number on the token the more powerful and valuable it is, so you want to try and manipulate the board to get the best possible tokens.

That’s how the basic gameplay works, and after a few games you’ll be comfortable with that. Then there are also abilities that come with the tokens that you pick as you play. Red tokens give you extra moves. Yellow tokens allow you to pick up additional tokens on your turn. Green tokens allow you to reduce the value of a token, making it easy to pick up, and blue tokens are worth double the score.

Using those tokens adds another layer of strategy, and play continues on like this until no one is able to pick up a token on their turn. When that happens, the point value of all the tokens is tallied, and the person with the most points win.

This is a highly strategic, intelligent, and challenging system that is quick to learn, but the number of variables at play makes it extremely difficult to master. It would be one of the best and most competitive board games on the Nintendo Switch except… there’s no online play. There’s local multiplayer, and AI opponents (of one difficulty setting only). There’s absolutely no way to play online.

This game needs online play, and I really cannot believe that the developer of a digital board game didn’t consider it to be essential. I realise that the community for it is probably about ten people strong, and I also realise that online has a cost attached to setting up servers for online play (thought peer-to-peer isn’t so demanding or costly). I get the costs involved, but if the developers couldn’t make that work, then perhaps they should have considered whether it was worth producing the game at all.

With no narrative, no variable AI, and no continuity to playing (there isn’t even basic statistic tracking like win-loss scores), as good as Kashido is – and I must emphasise that it really is a fascinating game well worth learning and playing – it fails in its basic task of actually helping people to actually experience and want to invest time into this game. No digital board game should lack online play. We’re all better off importing physically copies of Kashido and taking it along to chess club meetings to see if we can get them to give something different a spin.

Buy the hottest games with Amazon.

By purchasing from this link, you support DDNet.

Each sale earns us a small commission.