Unfortunately for Crymachina, NieR: Automata exists, and so as a concept “post-apocalyptic world where robots ask existential questions about what it’s like to be human,” is probably a theme that should be scratched from all other developers’ brainstorming sessions. Despite that very prudent advice, the team that took on Crymachina either missed the memo, or sure has some incredible proverbial gonads to try and follow up Yoko Taro’s masterpiece. Crymachina is not as devastatingly brilliant and won’t dethrone NieR: Automata in the eyes of the mainstream. It does, however, have a rich heart and soul, and may just get you to shed a tear by the end of it.

In Crymachina, humanity was destroyed by a particularly nasty pandemic (I’m assuming that this story was written sometime after 2020 started). Before the last humans disappeared, however, they had the foresight to create a massive spaceship – Eden – send it into deep space, and populate it with several incredible and powerful AI machines, tasking each with researching and developing some way to recreate humanity synthetically using the memories of humans that have been converted into “data”.

However, something goes wrong and most of the AI machines turn on the project. You play as a team that one of the remaining “good” AI beings creates to fight back and complete this mission. The team does this by physically slashing their way to the cores of these various AI, overcoming their servants and their own human-like avatars along the way. As they do this, our team of messiah-like “first people” are also gathering experience, which your ally AI tells you will eventually help each of them experience an awakening and achieve a state of human awareness.

There’s a lot of science fiction going on within this narrative, and the game takes plenty of time to also explore favourite sci-fi brain bubbles like Ferni’s Paradox (if there are other intelligent beings out there, why haven’t we encountered one?), various theories of psychology and, of course, the nature of God (because what sci-fiction worth its salt would not?) “God, too, is a human creation, therefore man is God,” says the friendly AI in the very opening sequence. Oh, and the main girl is a misandrist that really hates humanity, just to get a bit of droll ironic humour in there. Most of Crymachina is so pop-philosophy that it’s a cliché, but it’s also a series of genuinely interesting and timeless thinking exercises. Like all this game’s many thought experiences it’s handled without much nuance, but also without being condescending or trite about it. So it hits the right notes for anyone who likes their JRPGs with a bit of smarts to muse on as you play.

What did surprise me about the game was just how human its core turns out to be. Between missions, the entire team hang out in a “tea room” that allows them to have conversations with one another. These can be really sentimental at times, and then when the tears start flowing (they’re a motif and there for a reason), it can be surprisingly touching. Basically, for a game about robots and where humanity has been wiped from existence, Crymachina really gets to the crux of what a human story looks like. In that way it does somewhat differentiate itself from NieR: Automata, which wasn’t particularly sentimental and even somewhat dry in its observations.

Now that we’re talking about the differences between the two games, while they do share very similar narrative characteristics, Crymachina plays totally differently to NieR: Automata. Unfortunately, because it wasn’t made by a team of the talent of PlatinumGames, it doesn’t play nearly as well, though it’s still enjoyable. It’s essentially a brawler, where you travel through some smallish areas, defeating small groups of enemies, before taking on a boss. Defeat that boss, enjoy some more chats between the characters, and then set your sights on the next boss battle.

Everything that you’d expect from a modern brawler is there. By stringing together enough combos you can put enemies into a break state and then rip a big chunk of their health away with a single attack. There’s also a parry button that, timed just right, gives you a momentary advantage in battle, as well as limited use skills and a dodge manoeuvre, though I actually found the latter to be too clumsy when the parry mechanic worked just fine.

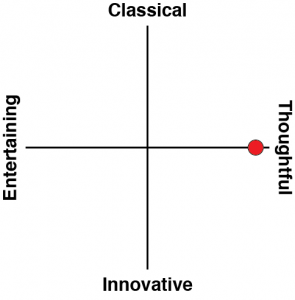

There are some good dynamics and energy in the combat, and it flows nicely. The only problem is that, especially in handheld mode – it can be a little hard to keep up with the intricacies of the action. The really big attacks are telegraphed with a light show, so they’re not a problem, but more than once I stared dumbfounded at the screen trying to figure out what had just caused my character to lose a chunk of health. It doesn’t help that the combat can be so fast it feels button mashy at times (especially if there’s a crowd around), but thankfully the impact of those incidences is uncommon, and for the most part, the game has a nice, graceful, and fast flow to it. In fact, at its best, there’s a dance-like elegance to the movement and attack strings that comes across as really very intelligent and thoughtful design. It’s like the developers worked really hard to give the visual impression of the cold steel of robots clashing in such a way that it was like there was a distinctly human soul to the action. Thus the combat reflects the discussions being played out through the narrative.

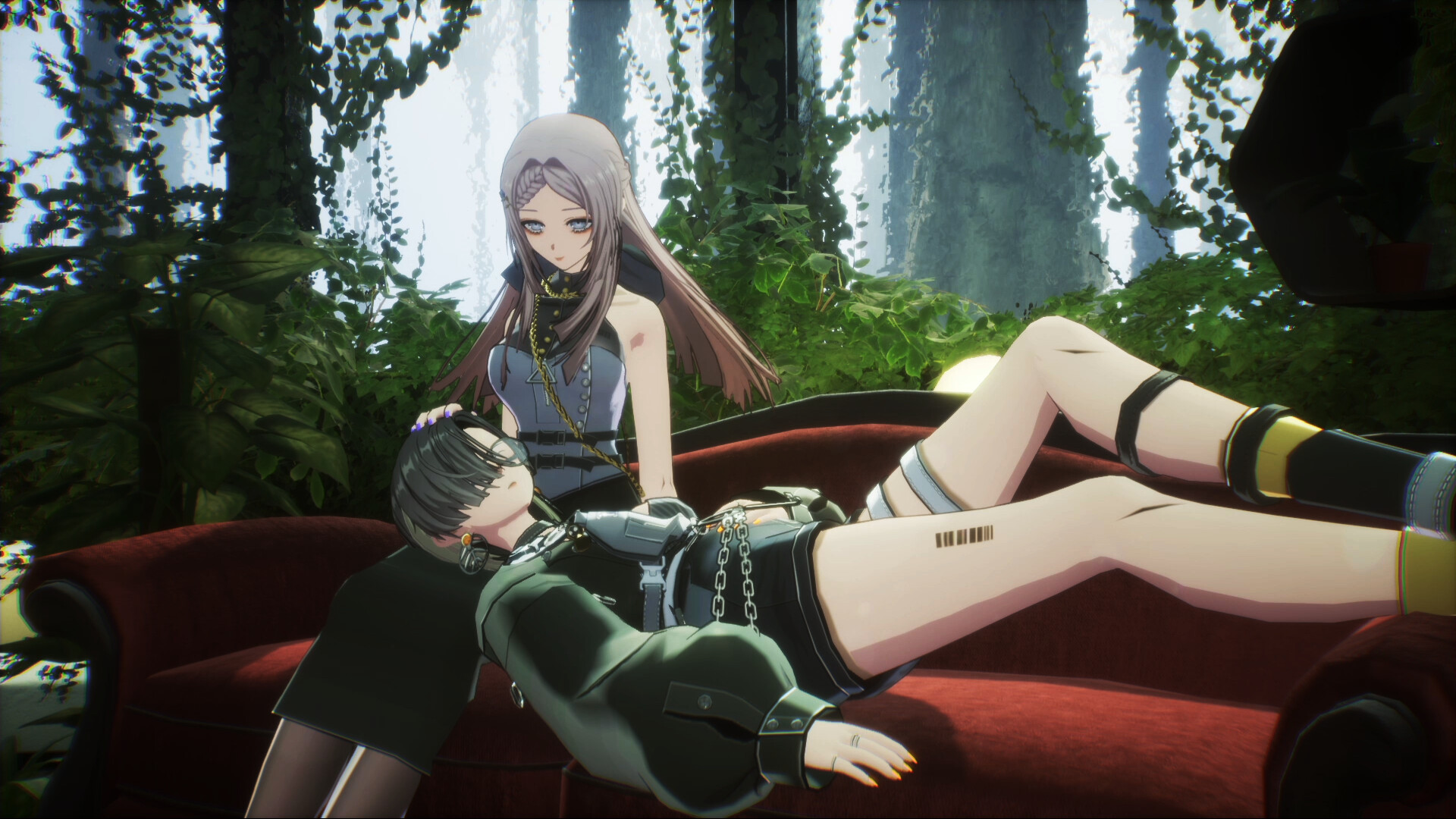

Another area where Crymachina really distinguishes itself is in the art. The artist behind the characters is a talent named Rolua, who has worked across a lot of media, but as far as I can tell, this is their first major video game project (some mobile titles aside). I hope there’s more to come, because there’s something both coldly alienating and yet beautiful about Rolua’s style, and it’s perfect for a game about the contrast between not-human robots trying to ponder the meaning of life and arrive at the truth of the human soul. Because so much of the success of this game relies on you empathising with these beings as they try to come to grips with the emotional and spiritual core that separates humans from machines, it was important that the character designs didn’t just catch the eye, but also intrigued and got you invested in them quickly. Rolua was the perfect find to achieve that.

In-game character models are more functional, and the developer uses the trick of making enemies as “mono-tonal machine” as possible as a way of concealing the limited budget that the developers were clearly working with. The bosses, however, are distinctive and interesting. While we’ve seen more creative and dramatic attack patterns from bosses in other games, the visual spectacle here is something special.

Crymachina asks probing questions about the nature of humanity through the lens of machines, and its conclusions are evocative, emotive and ultimately quite uplifting. It does sit in the shadow of a giant of a game that already canvassed exactly the same subject through exactly the same lens. However, there’s a greater warmth to Crymachina that makes it more relatable than the relatively academic NieR: Automata. Throw in some vividly memorable art direction and what we have here is a JRPG that might surprise people with just how memorable it proves to be.