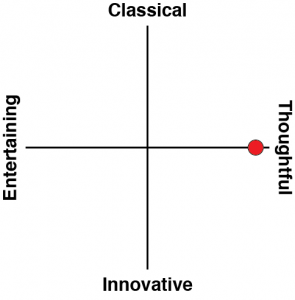

Final Fantasy XVI is a spectacular blockbuster that is also so much more than a simple “AAA-game”. Where most blockbusters aim to manipulate the player’s emotions but have little ambition beyond that, Final Fantasy XVI dares to challenge players with a narrative of depth and poignancy. It is the rarest of beasts: a big, explosive spectacle that also makes you think really hard about what it’s saying.

There are many themes at play across Final Fantasy XVI’s narrative, and they cross and intersect in surprisingly nuanced ways. The most overt of these is that it’s a thesis on war, with a strong emphasis on showing the impact that war has on its victims and innocents. As armies clash, cities are ravaged, and politicians manoeuvre, people suffer. Towns fall into ruin. Survivors struggle to shelter and feed refugees. The soldiers take what they want and brutalise those that have nothing that they want. This is a dark world that the development team have depicted, and the influences from Game of Thrones and other such dark and political commentary fantasy are blatant.

This kind of fantasy is timely, just like Game of Thrones. As Ronnie Olesker notes in an essay on Game of Thrones that applies equally well to Final Fantasy XVI: “Popular culture provides a ‘social grammar’ of our time by holding up a mirror that allows us to explore what we think about ourselves in a particular time and place. It can be used to explore dominant norms, ideas, and beliefs, if it is treated as a knowledge production site in which the values and norms of a particular society are created. Popular culture has a demonstrable impact on political behaviour and attitudes and is therefore ‘at least as influential – or, under some conditions, even more influential – in shaping people’s worldviews as more ‘respectable’ sources’.”

Final Fantasy XVI does this by being greatly concerned with the hubris and lack of concern that politicians and powerbrokers have for the collateral damage they cause to the populations that they’re meant to be protecting and providing for. As far as almost every political leader in Final Fantasy XVI is concerned, war is indeed a game. They’re all explicitly narcissistic and psychopathic and have little concern for anyone, beyond their utility in achieving their goals. To these elites, war is nothing more than an opportunity to further their own wealth, position, and interests, and as they play at being great generals and pursuing their petty grievances and vendettas, they demonstrate little concern for the misery and destruction they leave in their wake.

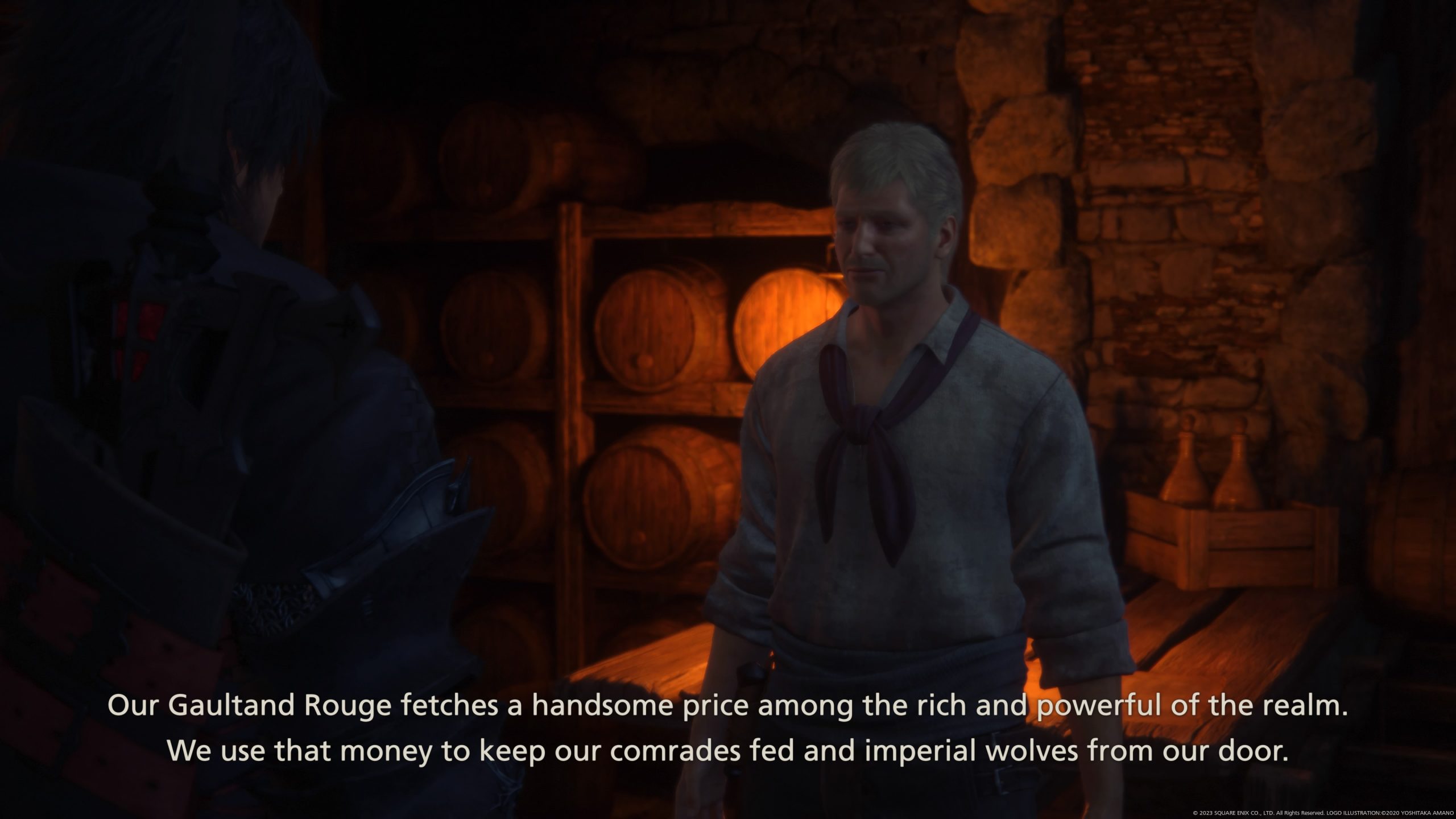

The people know it, too, and rather than look to the nobles and their militaries for aid, the commoners instead rally around community leaders. One such leader runs a town’s brothel. The influence that she wields over the garrison soldiers that rely on her girls for entertainment makes her the de facto head of one of the safest refuges within a viciously xenophobic and brutally violent empire. Another owns a bar and uses her wealth to help save as many slaves as she can (more on this soon). A third is a blacksmith-by-day and crime lord-by-night that conducts sabotage and subterfuge operations to undermine the iron fist that the wealthy and their military hold over his town. It falls to these common people to provide where the wealthy will not, and while Final Fantasy XVI is as gritty and dark as Game of Thrones, it differs in that there is a sense of desperate hope that comes from being part of this resistance and underground rebellion. Given the world we live in today that tone and theme is a “fantasy” in the truest sense of the world.

Even more shockingly relevant is the way the game works as a metaphor for climate change. There is an apocalypse impending in the world in Final Fantasy XVI. There is a blight that is sweeping over vast swathes of land, blackening the dirt and rendering the entire environment an inhospitable wasteland as it passes through. Formerly fertile farmland and entire villages need to be abandoned, and the most affected nations need to look at military solutions to relocate their people to lands that can still sustain a human population. Even when those lands are already inhabited.

Again, though the leaders of these nations are all depicted as being completely unconcerned by the doom. They’re still too busy throwing their armies at one another to further their political ambitions. Their bellies remain full even as crop failures send starvation rippling through the peasantry. For their part, the population is too poor, hungry, and fixated on simple survival for anyone to organise and attempt to look for a solution. They have little recourse but to move on when the blight finally starts withering their farms. When we look at the flagrant disregard the world’s political leaders have for the need to take meaningful action on climate change, and the way that the most heavily consuming elites try to push the responsibility for sustainability onto individuals, it’s really difficult not to look at Final Fantasy XVI as a powerfully symbolic parallel in this regard.

Then there’s the way the game tackles racism and xenophobia. As a quick side-note: During the preview season and in the lead-up to the release of the game Final Fantasy XVI was targeted for a lack of “diversity” by people who hadn’t actually played it. In fairness, this wasn’t helped by a less-than-wise response from the developer, but the game is also not the “diversity fail” that it has been labelled as. There are many ethnicities present in the game. Yes, there might not be a character coded after African Americans, but in addition to the multiple distinct European ethnicities, there is an entire nation that is explicitly Middle Eastern in aesthetics, culture and ethnicity. Final Fantasy XVI is a different vision of a “melting pot” than is standard today, but while it’s less arbitrary about it, diversity is very much present. In Final Fantasy XVI, there’s no particular animosity between the different ethnic communities (remembering that their constant warfare is more to do with political machinations), but the developers do explore the subject of xenophobia via the use of a branding. In this world, people who have magical abilities are given a brand on their faces. This immediately drops them to the bottom of the social caste. They are enslaved in many nations, and even in those where they are “free” they are treated viciously.

The treatment of these people is often deeply uncomfortable, and the game doesn’t hold back in depicting the worst edges of society. One of the most memorable side quests in the game is when a wealthy man begs the protagonist, Clive (at this stage a branded himself) to “rescue” his son from a vicious monster. Clive does so, only to discover that the monster was actually a trained pet and the son was in no danger at all. So cruel was the father that this was a game that he and his son liked to play. He’d send well-meaning branded people to their deaths by playing on their empathy and desire to help. There are times when the treatment of xenophobia as a concept is so extreme that it almost slips into caricature. However, we as a modern society really have mainstreamed xenophobia (separate though linked to overt racism) and it has been naturalised into our societies to such a point that the theme needed to go over the top to make it truly uncomfortable to witness.

Servitude is a theme that extends beyond the branded slaves, too. In Final Fantasy XVI, the “summoner” role that is traditionally part of the Final Fantasy canon has been renamed. Now these characters are “dominants.” They do the same thing as a summoner, in that they channel a part of themselves to bring the usual crew of impossibly powerful creatures into the world, but the implication and meaning behind that new term is significant. Clive himself is a dominant, with Ifrit as his summon (“Eikons” in this game’s language). You’ll then run into Garuda, Titan, Shiva, Ramuh, Bahamut, Odin and so on through your journey.

Related reading: From the DDNet podcast: Our favourite moments from Final Fantasy.

The relationship between dominants and their summons is less benevolent than is generally portrayed in Final Fantasy. The summons that resides inside the dominants slowly eat away at their hosts every time they use their powers, before eventually consuming them completely. This is, of course, something of a morality play to reflect on how those with power over others should wield it responsibly and with respect, lest it consumes them. In theory, these powers would be able to do a lot of good for the world around the dominants. Sadly for the world of Final Fantasy XVI, most of them are corrupt and use their powers with both decadence and hubris. They, therefore, become a menace to all around them before the lust for power eventually sends them over the top. CEOs, basically. The dominants are a close metaphor for modern CEO behaviours.

One final theme I’ll highlight here (there are so many more that people will delve into in the years ahead) is the application of crystals. Crystals are iconic to the Final Fantasy series, and typically symbolic of the series’ fascination with deterministic philosophy. Typically, the crystals’ role in these games is to fate heroes to go on their journeys and save the world. “Everything is determined, the beginning as well as the end, by forces over which we have no control. It is determined for the insect, as well as for the star. Human beings, vegetables, or cosmic dust, we all dance to a mysterious tune, intoned in the distance by an invisible piper,” to quote Albert Einstein.

More recently, however, Final Fantasy writers have sought to challenge that idea. The Final Fantasy XIII trilogy had the idea of resisting fate at its thematic core, Final Fantasy VII Remake actually used its re-interpretation of the narrative to challenge the heavy deterministic themes of the original, and Final Fantasy XVI, here, is the strongest challenge of this relationship between crystals and determinism yet. Through much of the adventure, you’re on a quest to destroy the crystals, as they represent a malign drain on the world. The way it handles this is deeply subversive to the Final Fantasy property, and though you’ll no doubt read plenty about just how different the combat is, and how much that has broken from the norm, it is this theme that is the single best proof that Square Enix continues to see Final Fantasy as an opportunity to subvert, challenge, and rebuild tradition. In an incredibly risk-averse industry, Square doesn’t get enough credit for its willingness to risk real and fundamental change to its most valuable property.

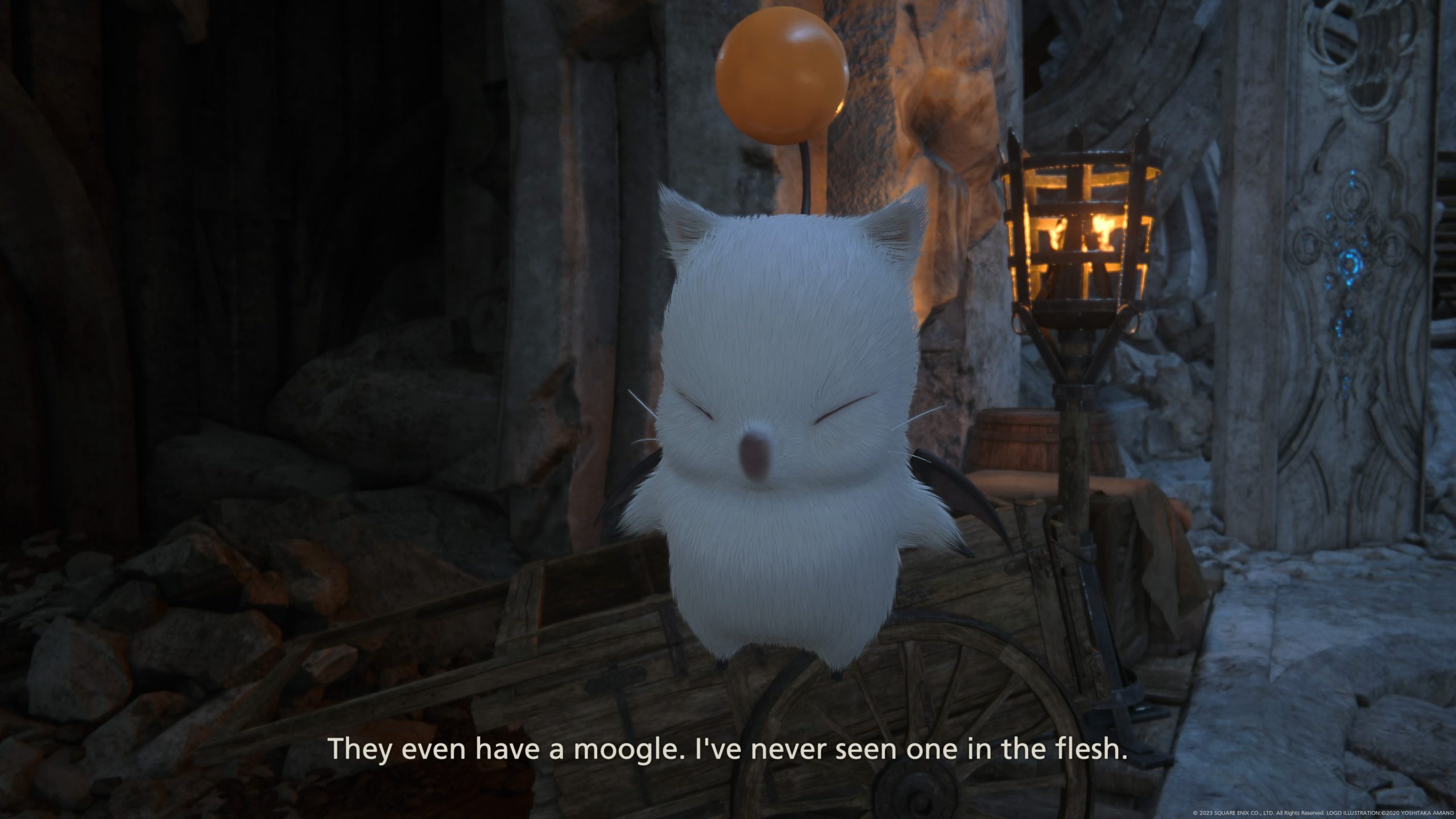

In other areas, Final Fantasy XVI retains the core qualities of the Final Fantasy heritage, and is filled with little nods and references that help to ground the game into a series that has meant so much to so many people for so long. For example, almost every little village with a “rest area” has a bard present, playing music to lift the spirit of the locals. All of these bards have names, except for the first one that you run into, who is simply called a “Spoony Bard.” Elsewhere, a Moogle hands you your monster-hunting quests, and those monsters are almost all iconic enemies direct from the bestiaries of the classic titles. At one point you need to go on a rescue mission to save someone, so he can build a bridge for you, and yes it’s a very blatant reference to Final Fantasy 1. Every Final Fantasy has a Cid, and this game’s Cid is perhaps the most consequential Cid there has ever been. There’s a moment that recreates the iconic scene at the top of a mountain in Final Fantasy IV, and I could go on for hours listing all these nods and references so I’ll stop here. Finally, and most importantly, the music is an exquisite most incredible blend of original compositions and references back to iconic tunes. As dark and sober as the narrative to Final Fantasy XVI is, there is also great joy and love for Final Fantasy in there, and spotting all the references as you travel the world is a gift from the development team to the series veterans.

The above is nearly 2,000 words focused exclusively on the narrative. There is a lot more to say, but the overall point here is that Final Fantasy XVI impressively has a genuine depth of theme and philosophy, but avoids mistakes made by some previous titles in the series (most notably the XIII trilogy) by delivering them without being pretentious or overwrought. In fact, a lot of the narrative is quite succinct and seems designed to do little more than drive the game forward. It’s only on reflection that you’ll realise that it actually has a lot to say. It’s so rare for a blockbuster in any medium, let alone games, to be so effective at being something that is hugely entertaining on the surface, but has a compelling thesis and depth of thought underneath.

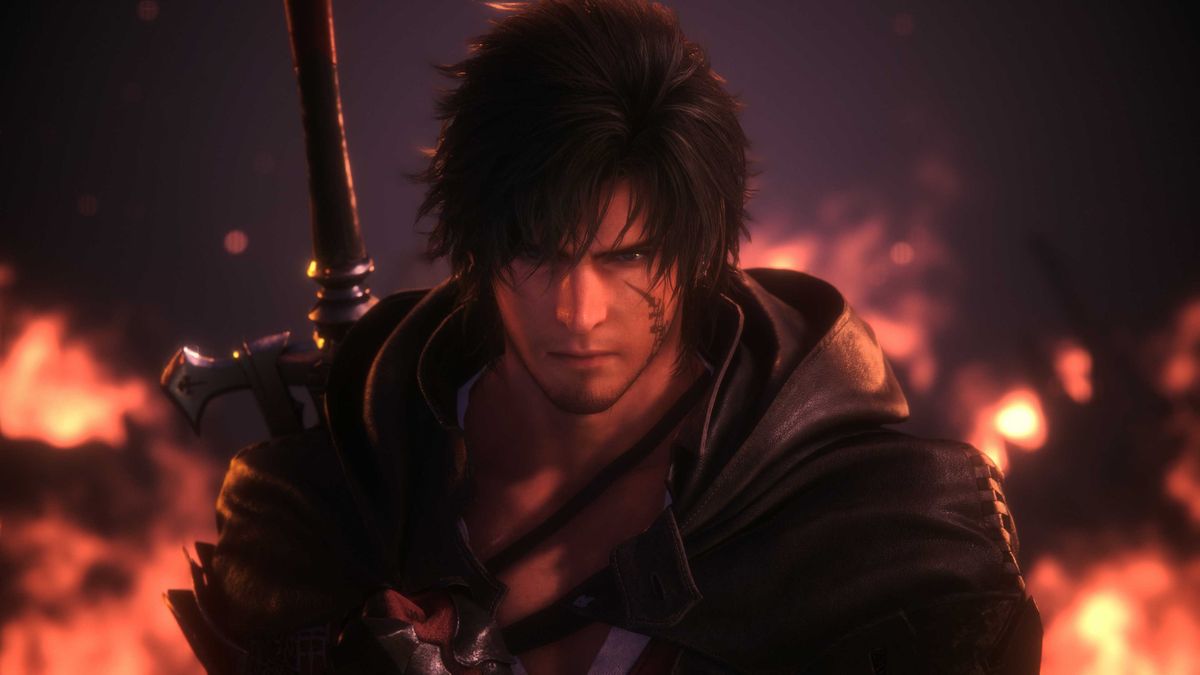

Without stellar performances, all of that would be for nothing. Thankfully, regardless of whether you’re playing in English or Japanese, the performances in Final Fantasy XVI are universally spectacular. At first, Clive will seem like a hero cut from the same cloth as Squall and Cloud. He looks like a stoic and dour type. That doesn’t last long, though. He’s a tragic figure, but not for arbitrary reasons, and his emotional conflict doesn’t manifest as the kind of simple anti-social caricature of Final Fantasy heroes past. Clive and his wolf companion are the only two permanent members of the party (and you only really play as Clive), but the rotating cast of allies that fight by his side all contribute by giving Clive different personalities to contextualise his own. There’s the oafish uncle, who gives Clive a chance to be a comedian. There is Jill, who draws a romantic side out of him. And there’s Cid who effectively acts as a mentor and moral guide. Thanks to his interactions with this ensemble cast of allies (and others), Clive is one of the most relatable, interesting, and nuanced characters in Final Fantasy history. And, again, every single performance is delivered perfectly.

If Final Fantasy XVI wasn’t able to captivate as a game to play, the strongest narrative and characters in gaming history wouldn’t save it. Thankfully, under the guidance of a Devil May Cry veteran, the combat system in this game is spectacular. Clive has access to two basic attacks, but can also use an increasing array of magic “boosters” to launch strings of special attacks. String those along effectively and the screen will explode with crackling energy, and it all feels very satisfying in the hands.

It is, however, not a JRPG at all. Square Enix has flirted with action combat systems in the past, and has gradually, over time, de-emphasised the stats management function that people generally appreciate in JRPGs. But they’ve always held just short of dropping out of the genre entirely. Even Final Fantasy XV had a rhythm to its action combat system that made it ultimately perform like an ATB turn-based system, and plenty of buffs and stats to manage, as well as a levelling system that made it feel like your team was getting more powerful with experience. Final Fantasy XVI goes far further than XV did.

There is levelling in Final Fantasy XVI, but you’ll barely notice the growth in power since everything’s so perfectly balanced that you’re going to stay right in line with the enemy’s power curve. You can boost statistics with three different pieces of equipment, but again, aside from the visual differences between swords, the actual effectiveness of them isn’t something you’ll pay attention to as you play. Inventory management is reduced to juggling three different potions, which you have exceedingly limited uses of between trips to the item shop to replenish. Final Fantasy XVI is by no means shallow and offers players a tactically nuanced and narrative-driven action. However, it has allowed Square Enix to finally move the series beyond the JRPG genre. I am sure this will disappoint some people, but to me, this series was always one where the gameplay was there to support the narrative. For such a dark and cruel world, having the impact of a true action system is far more appropriate and effective at furthering that theme than a more cerebral JRPG combat system would have been.

Related reading: The best pieces of music from Final Fantasy history.

Special mention must be given to the bosses, and, in particular, the battles with the dominants and their summons. Final Fantasy XVI is a very boss-driven experience, and it’ll be rare that you have more than three or four encounters with normal enemies before a sub-boss shows up. Soon after that, you’ll be facing a major boss. And then, at the most key moments in the game, you’ll tackle the dominants.

Sub-bosses will generally challenge you tactically, and threaten some of that scarce potion supply if you try and button-mash your way through them. Major bosses require patience and you’ll need to learn their patterns while slowly whittling down their health. The dominant battles are earth-shattering in their scope and visual complexity. They might only play more-or-less like a more difficult variation of the major boss battles, but these bosses fill the screen with fireworks and are ridiculous at their expansive scope, lasting upwards of a half hour or longer. In fact, they are so filled with visual energy and mechanical complexity that they can be draining to actually play, and tend to be a nice point to then put the controller down and go and have a think about the chapter that you just worked through. That’s not a criticism, but rather a comment that I’m struggling to think of boss battles that are a more staggeringly-intense experience than these. It’s a compliment, even if I’d hate to have to try to play them back-to-back.

Another quality of Final Fantasy XVI that deserves congratulations is that the developers resisted the urge to make it an open-world game. In fact, it’s very linear. You’ll come across many areas that are open enough to let you stretch your legs (and hide the occasional bonus, optional boss, and so on), so the developers should avoid the kind of anger that Final Fantasy XIII experienced with its “corridor linearity.” However, generally speaking, you are following a trail of breadcrumbs as you play. It was important to do this to control the pacing of the narrative (which is spot-on for keeping you engaged and preventing the adventure from stagnating), and it also allowed the developers to tune the experience so that you’ll never feel the need to grind, or be lost, or simply uncertain about what you should be doing next.

There will likely be some criticisms from a lack of side quests. You’ll generally only have two or three to complete between each major story beat, and they tend to be quite brief affairs. This, however, also shows maturity and confidence by the developers. Rather than simply throwing content at players for the sake of it, those side quests are additive to the narrative or worldbuilding in some meaningful manner, and also don’t allow players to become so overwhelmed that forward progress through the game stalls. This is exactly how I want side quests handled from now on, in that they’re there for a reason and not for busywork.

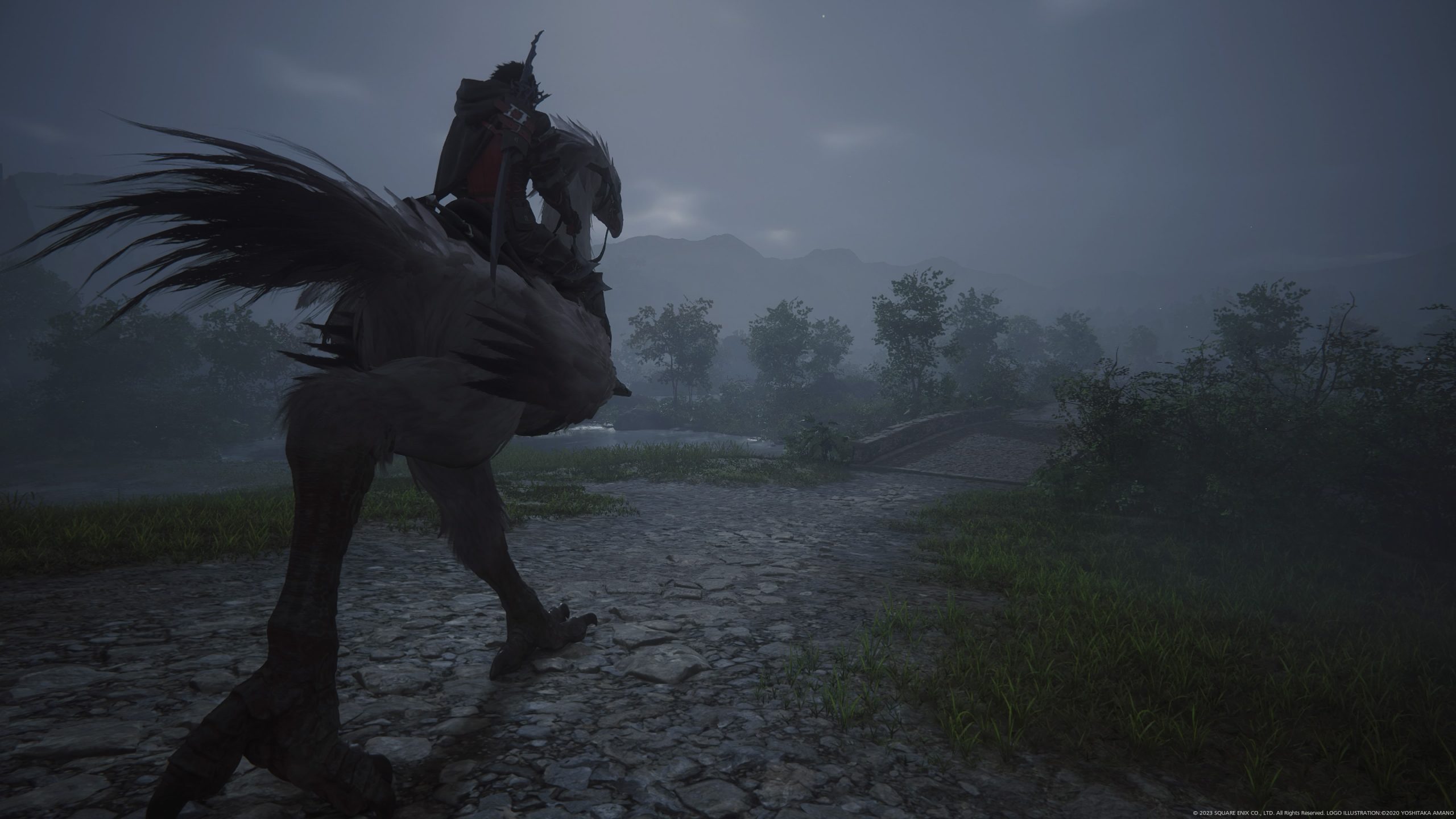

To finish this overly-long review on two quick notes: firstly, Final Fantasy XVI looks every bit like a true blockbuster. We very rarely get Japanese games that are developed to this kind of scope and budget, and it’s interesting to compare it to the Sony and Ubisoft blockbusters that we’re much more used to. There’s a more fantastic use of colour in Final Fantasy XVI, and an aesthetically pleasing artificiality that contrasts with the efforts of most Western studios to present something more grounded and naturalistic. Where Western developers work hard to blend the fantastic (such as the robots in Horison or the clickers in The Last Of Us) with the real, Final Fantasy XVI is happy to have Chocobos and Moogles dropped into a world of European-style castles and armour, and juxtaposed in a way that you’ll never mistake this for anything but a fantasy. That’s a subtle difference in aesthetic and design philosophy, but it’s one nonetheless. Even given the grim and serious tones of the game, Final Fantasy XVI is a world of beautiful people and gorgeous, deeply and richly coloured environments, and more a case of romanticism than realism.

Secondly, while the accessibility features in Final Fantasy XVI are not up to the same level as the brilliant work that Sony and Microsoft, in particular, do in this space, this is a highly accessible game for most players. There are several “accessory” items that you can equip to Clive that then allow you to then bystep the more demanding elements in the combat system. For example, there’s an item that allows Clive to automatically dodge any attack that can be dodged. Additionally, as hectic as the combat is, it’s actually not that difficult, and all bosses have interesting but learnable attack patterns that almost never rely on a player’s ability to execute a twitch response. Furthermore, if you fall to the boss, you can automatically retry with all your potions back, and the boss’ health at whatever you previously reduced it to. Elden Ring and Devil May Cry aficionados might find it all a little too easy for their tastes, but for the mainstream, Final Fantasy XVI has hit a really nice balance between a combat system that feels like you’ve earned victories, while making sure that as few people will throw down their controllers in frustration as possible.

It’s far too early to determine where Final Fantasy XVI sits in the ranks of Square Enix’s venerable series. However, this is an engrossing, entertaining and, most importantly, fiercely intelligent game. The developers have taken the AAA-blockbuster budget they had to work with, and used it to craft an experience with a strong, provocative and timely message, and then backed it up with some of the most entertaining action combat we’ve ever seen. Not a second of the game’s runtime is wasted, there’s not a single dud character, moment, or scene, and the plot is a riveting epic “page-turner.” If only more blockbuster games were like this, game development would be a far more mature art form.

As always your reviews are the absolute best, thanks for the very detailed review.

I greatly appreciate it.

Agreed, very interesting and thought-provoking review!

This is a stellar review and I enjoyed the GoT essay reference and Albert Einstein quote. I had planned on waiting to get this for Christmas but after playing the demo, I was hooked on the story and the characters, so I went ahead and bought it.

One thing I had trouble with early in the game was all of the proper nouns and various country alliances, but the Active Time Lore feature does a lot to help with that. Still weighing how I feel about the linear nature of the game environment, especially the trivialities of field items. But as the story and writing are so good, it’s hard to complain about the game being linear when you can’t wait to see what will happen next!

So far I love the voice acting, especially the gentleman who voices Cid. And the relationship between Clive and his loved ones is surprisingly touching, even for a FF game.

Graphics also show off the power of the PS5. When you first visit Cid’s hideout, I was blown away by the lighting and architecture. Just an all around great game!

Thank you! I’m really glad you enjoyed the review, and more importantly, I’m glad you’ve been enjoying the game! It really has stuck with me in the months since finishing it myself. I’ll have to figure out when I might have the time for a replay :-).