The Lord of the Rings: Gollum is not a good game. I “awarded” it the rare 0/10 score here on DigitallyDownloaded.net, and most of the other critics have not been much more positive about it. As always happens when a game is a disappointment on any level, the fangs from gamers have also been out in full, and the developer felt the need to issue a grovelling apology. So today, even after writing that review, I’m going in to bat for the game, in a way. To be blunt, people need to learn that it’s okay for games to be bad.

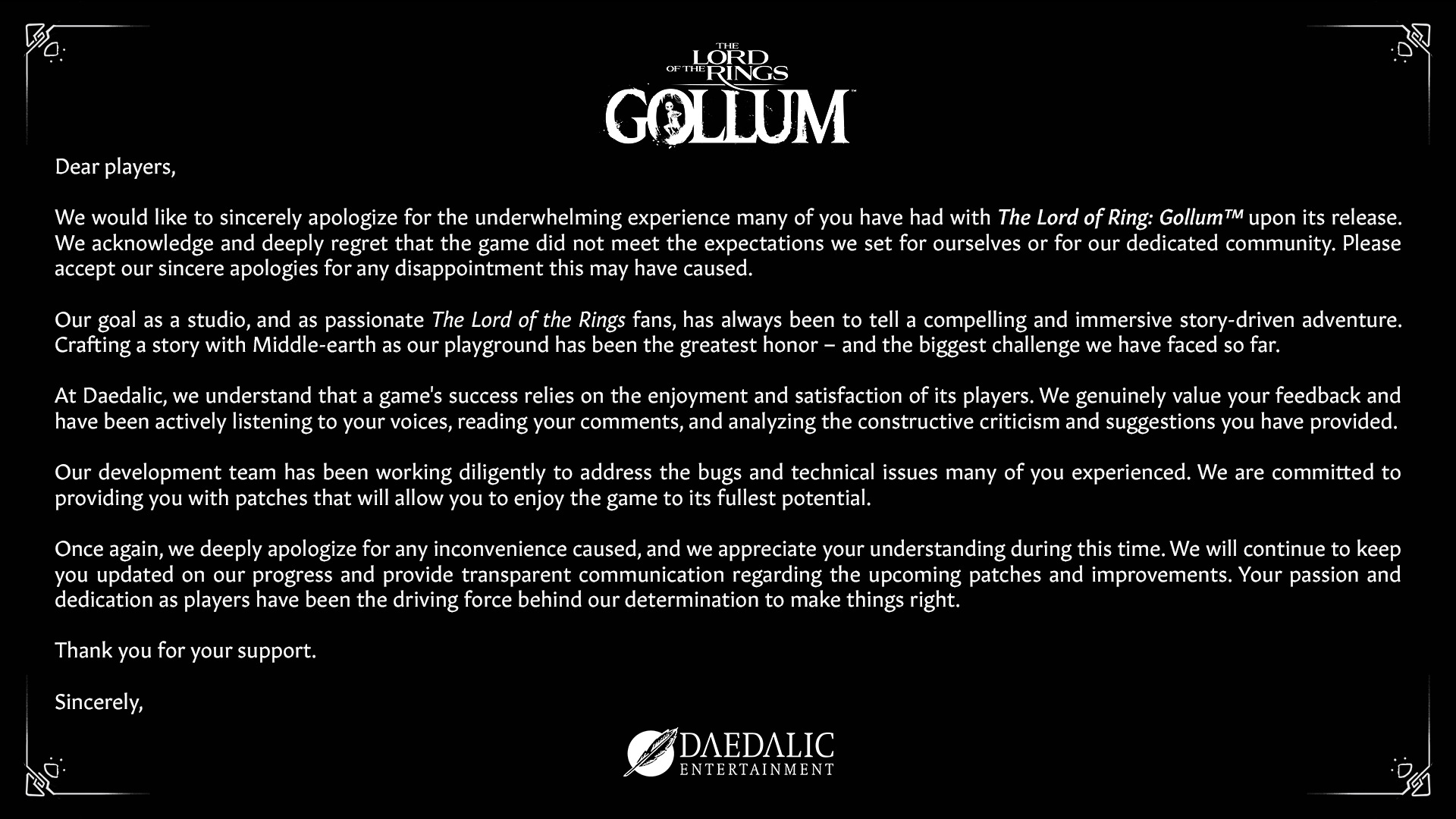

You only need to look through the responses to the apology to realise that there are a lot of people out there that expect every game they purchase to be good. It’s one thing to be annoyed at a company for shipping a game with bugs that need to be patched, but the criticisms of Gollum go well beyond that. The game has visual issues and simply doesn’t play that well. Those aren’t bugs, yet people are including those in their evisceration of the developer. Even it Gollum does get patched to the point that it runs flawlessly, it’s still going to be a poor-quality game.

And people need to learn to be okay with that.

If video games are an art form, and again I emphasise if, because every time that subject comes up it seems that fewer people have any interest in games as art works, then they are a creative endeavour and not product development. This means there is an inherent risk that things don’t turn out well. A creative endeavour means that either an artist, or a team of artists, sit down with an idea of something that they way to express through their work, and then produce something that reflects their specific, personal vision. Authors have stories they want to write. Painters have a picture in their minds that they want to get down on canvas. And game developers, in theory, should be working on visions of their own.

A product, meanwhile, is something created specifically to appease an audience. A newly developed flavour of canned soup is focused grouped to death when in development, and feedback from those focus groups affects the ingredients that go into the final product. A company like Coca-Cola tests a new drink in a limited market (like, say, Norfolk Island), to see how it resonates with a tiny test audience before it takes the product to a wider audience. Why do they do that? So they can fine-tune formulas before it’s too late, because in the FMCG space, there are no second chances on first impressions, and it’s best to test on a tiny sample market before the reputation for the product goes wide.

The goal of product development is to ensure that the product appeals to the broadest possible market. This is something that the suits sweat over, and there are three basic ways that they break consumers down: TAM, SAM, and SOM. TAM is the “Total Available Market”, and that means the total maximum audience if every single person bought your product. So, for example, if you were running a fast food chain, what is the total global audience for fast food, and what if they all came to you because there was no competition? That is the TAM – it’s a mythical number that a business can never achieve, but it reflects the absolute maximum audience out there.

SAM, meanwhile, is the Serviceable Available Market. This represents the maximum number of people that you can reach with your product right now. So, for example, if your fast food chain is only actually operating in two cities, then the SAM is actually just the population of those two cities (and, more realistically, a certain radial distance to your restaurants from within those cities, since people aren’t going to travel for hours for fast food).

SAM, once again, doesn’t account for competition. SOM, the final term, is the most likely audience for your product once you include the fact that consumers might prefer an alternative to your restaurant. The closer you can get your SOM to your SAM, the more “mainstream” it is in terms of its appeal, and consequently it means that investors will like your business more and the money will roll in. And so, to give you the best possible chance of maximising that SOM, you try and make your product appeal to the widest possible demographic within the SAM group.

This works for niche products as well as mainstream products. In niche products, the SAM will be smaller, since the biggest audience you can reach is the totality of the niche, and so it’s all the more critical to make the SOM closer to that SAM value. You want to capture as much of that niche as you possibly can. The SAM for Lamborghinis is smaller than the SAM for Toyotas, for example, so Lamborghini works all the harder to listen to every one of its consumers when designing cars. But, the point here is that no matter what the product, no matter what the field, and no matter how niche it is, your goal in each instance is to put the consumer at the centre of what you’re doing.

When you apply this to the arts – and it absolutely happens in all art forms, unfortunately, because the suits still run these companies – what you get is artists compromising their artistic vision in order to produce increasingly homogenised films, games, and whatever else that aim to maximise the SOM group size. That is the consequence of trying to make the SOM and SAM a perfectly aligned circle. You’re aiming to make “something for everyone.” The impact of this was expressed really nicely by filmmaker, Dexter Fletcher, recently, when he was interviewed about the film, Ghosted, that he produced for Apple TV+.

With streaming services all scrambling to maximise their SOM metrics, the films being produced for them are being compromised as artistic visions. As the interview highlights:

“You can’t make a film for streaming the same way you do for theatrical,” Fletcher told Alex Zane’s A Trip to the Movies podcast. “There are different metrics and approaches. There has to be, for the very reason that people can turn off very quickly.”

The Rocketman filmmaker continued to say that he had initially planned a long and elaborate opening sequence for Ghosted that involved Ana De Armas driving a car through a mountain in reference to a scene from the 1978 film Foul Play, starring Goldie Hawn and Chevy Chase. Fletcher said he took the scene to Apple, who said they understood what he was attempting to create but raised concerns about whether it would resonate with a streaming audience.

The result was, indeed, a totally homogenised action film. You can watch it, and enjoy it enough, but that comes with the consequence of Ghosted having nowhere near the creative impact that Fletcher’s films have had when he’s been able to follow through with his own creative vision.

Creative processes should never involve TAMs, SAMs and SOMs. The suits running the publishers need to worry about this in an overall sense, and this means they should be circumspect about the projects that they greenlight. It means that there will be some art works that simply never get made because they can’t secure a backer. However, once funded, the artist should not be worrying about these things.

Backing the artist’s creative vision like that does sometimes mean an art work will be terrible. Sometimes a creative idea simply does not work. A game about Gollum was unlikely to ever really work. Gollum is a significant character to the Lord of the Rings, but he lacks the narrative depth of, say, Frodo, and the physical presence of one of the characters like Aragorn or Gandalf. He’s just not video game material. The developers got to give it a go, and it fell flat. Fine. The point here is that we should accept that and that grovelling apologies for missing the mark should not be necessary.

Again, to be abundantly clear, bugs are an issue and it is fair enough to complain about those. Those sit outside of the creative vision (and indeed are a detriment to it), since no artist is looking to make something that is technically flawed. However, it’s important and necessary that we understand that a bug-free game will still sometimes be a 5/10 experience – if not even lower – because that’s a consequence of the creative process.

I don’t regret buying Gollum, at full price, even though I currently have the lowest score review for it. I am glad that the developers got their chance to work on the game, and while I’ll never play it again, I appreciated the opportunity. It’s only by playing the bad that we can truly appreciate the great. That’s just how art works, and developers shouldn’t be apologising for it, nor should the audience be demanding that we treat games like we do canned soup. Anyone that truly wants to avoid games becoming homogenised – or “samey” as you see constantly in user reviews – should acknowledge that this does mean that sometimes they’ll play something they don’t like, and they should be okay with that.

Agree with all this. “Bad” can be interesting in the sense that you can look at what the artists were trying to achieve, and how well they achieved that. Sometimes there are worthwhile things to be picked out from even the most seemingly flawed works — and sometimes, as is seemingly the case with Gollum, the conclusion is that “this was a bad idea in the first place, and the final product demonstrates exactly why”.

In fact, anyone analysing any sort of critical work should be placing the questions “what was the creator trying to achieve, and how well did they succeed at that?” at the core of their analysis. Sometimes creators achieve what they set out to do, and that’s usually a good thing. Sometimes they fail to achieve that, and that can be interesting, too. And sometimes they can “accidentally” achieve something completely different along the way, also — for me, these are always the happiest discoveries.

But yeah. Any time I see a JPG of a grovelling apology such as the one I see above, I cringe a bit, particularly when it’s worded in corporate bollocks like that one is. Oh, we’re so so sorry that the *product* we created for you to *consume* was not up to the standards of *quality* and *excellence* you’ve come to expect from our *brand*. We hear you. We’re listening. etc.

I actually find it more interesting to review “bad” games, because there’s so much to pick apart with regards to intent versus execution and the discussion on how things can go wrong with the artistic process. Not that I don’t like playing good games, of course, but without the occasional Gollum this gig would get intensely boring.

I agree with a lot of what you say here, and the middle portion of your essay is very interesting to those of us who aren’t in marketing or related fields. It really makes sense that one big reason art and entertainment is so homogenized these days (which most of it really is) is that decisions are made by suits looking at SAMs and SOMs, not by artists who are free to be true to their own idiosyncratic, inspired, imperfect, fiery and challenging vision. I have thought a lot about these issues, but would need to write a response at least the length of your essay to express them! Maybe one day…

Just one quick point:

– You never defined for your reader what the acronym SOM stands for: “Serviceable Obtainable Market” — but like any attentive reader, I just went and looked it up. Interesting stuff.

“Just one quick point:

– You never defined for your reader what the acronym SOM stands for: “Serviceable Obtainable Market” — but like any attentive reader, I just went and looked it up. Interesting stuff.”

Oh wow. How did I overlook that, lol. Thanks for pointing that out (and for checking it out)! It is interesting how businesses determine what kind of potential market they have. I’ve done a lot of work in this area and, as critical as I am of corporations and capitalism, the thinking behind the stuff is fascinating.