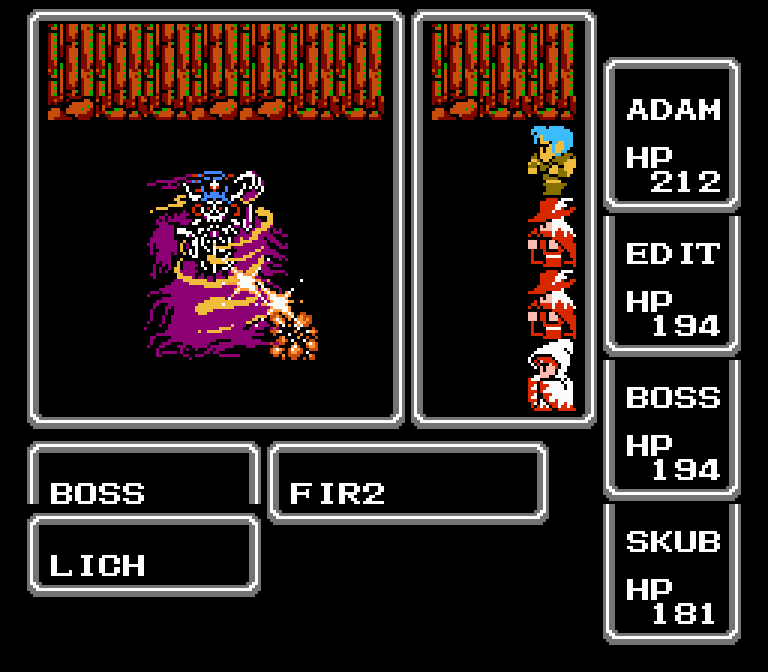

Once on the DDNet podcast, we got to talking about “canon” games – ones that many people would consider to have historical or aesthetic significance. These are games that are worth going back to, even after technological increments have iterated and refined their design. For the JRPG genre, we immediately thought about Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy – foundational titles from the NES era that codified concepts like overworlds, turn-based combat, themes like crystals and destiny, and the aesthetics of the slimes and Final Fantasy’s iconic sprites. These are influential games that are important and worth playing, while paradoxically also being games that none of us would recommend playing in their original form, since they’re also tedious, esoteric, and punishingly difficult.

People usually think of this era of the genre as outdated, rife with harsh design decisions like too- frequent random encounters, punishing dungeons and a lack of save points. Beyond historical preservation, it’s often argued that there are few reasons to go back to these games. The JRPG is a genre particularly known for spawning long-running franchises – for every series that started in this era, every Dragon Quest, Final Fantasy, Phantasy Star or Megami Tensei – the “best” one that you would recommend to a player is also never the first one.

But within these originators lies a design ethos that is absent from the modern genre – a simplicity and abrasiveness which make the adventure worthwhile. Whereas Final Fantasy VII or Persona 4 are games that you finish, Dragon Quest 1 and Final Fantasy III are games you conquer. You brave the depths of a game trying its hardest to prevent your forward progress, and you emerge with your perseverance tempered.

It Started With A Quest…

The best place to start with these games is with the original. Enix’s Dragon Quest stands as a testament that within the basics of the JRPG formula, there’s something worthwhile and lasting. Hopefully, you like defeating monsters, gaining EXP, crawling dungeons and repeating, because that’s all there is to do here.

Its story is… well, it doesn’t have one. There’s a dragon lord enacting evil across the kingdom, and you’re the reincarnation of a legendary hero, so grab your gear and go fulfil your destiny. But while the in-game story is sparse, the narrative is rich. Despite being a warrior of legend, you start out with merely a wooden sword and cloth robes, and the only enemy you can dare face in single combat is a grinning blue slime. They give out just one gold and one experience point each – the most miserly reward possible in a JRPG – and you need 10 experience points for your first level-up.

If you take the game’s command to “Venture Forth” too enthusiastically, you’ll wander across the northern bridge and encounter a genre staple – the difficulty spike. This is where the way forward is not impassable but impedes player progress by scaling, or “beefing” up the strength of enemy encounters. In Dragon Quest, the first time most players will hit this is when they run into scorpions for the first time. Those beasts of doom (to young adventurers) are armoured and can dish out huge amounts of damage in one hit. There’s no moving forward until the player can effectively deal with them, and the only way that’ll happen is with time and effort.

Now some might see this as an example of frustrating game design. There are gentler ways of preventing player progress, like a broken bridge (as the first Final Fantasy does) or requiring a new form of transportation, but the beef gate represents something special to the genre’s early days: grinding. It’s a way of signalling to the player that the reason they can’t progress the story and be the hero they were destined to be is that they’re not strong enough to visit this area. Yet. Because if the player could simply walk across the hills and barge into the dragon lord’s lair at the game’s onset, the narrative would have no weight or gravity, nor would it convey the sense of an epic journey. No, the NES-era JRPG forces players to bide their time, to get incrementally stronger across a long adventure, and even then, once scorpions are no longer scary, subsequent areas will present even more fearsome enemies.

Scorpions become meaningful foes because you remember their attacks tearing through a Cloth Tunic – so when you can finally afford Leather Armor and have a few extra levels under your belt, the ability to defeat them is a crystallisation of your perseverance. But then you’ve got Golems to worry about, and suddenly that Leather Armor doesn’t look adequate. Back to the grind, then.

It’s hard to describe this gameplay loop without making it sound tedious. All the player is doing is hitting buttons in repetitive patterns until the game tells them they’re adequately strong. On paper, this should be terrible. But the experience triggers something deep-seated in the human brain, the desire for progress, and the demand that effort be rewarded. When a new milestone is reached, a spell is learnt, or a dungeon is beaten, there’s a rush of pride that’s unparalleled.

A Period Of Grand Experimentation

With the foundation of the genre laid by Dragon Quest, and with monumental commercial success up for grabs, the late NES and early SNES eras were dominated (in Japan, at least) by developers trying their hand at recapturing the magic of Enix’s original title, but with their own unique spin. What defines this era for me is the way developers were fiddling with what we today consider the “JRPG formula”, but what was back then entirely unestablished.

Aesthetics diversified. We often erroneously think that the Final Fantasy series, specifically VI, drove the genre’s interest with its fusion of traditional fantasy with science fiction elements, but merely one year after Dragon Quest, SEGA’s Phantasy Star took their JRPG to a futuristic dystopia, and while it’s remembered, it still struggles to be attributed with that success. In that same year, Culture Brain explored Arabian aesthetics in The Magic of Scheherazade, and Atlus’s Megami Tensei series began with Digital Devil Story, a science-fiction story infused with a syncretic take on religion and the occult. It would actually be another few years before Enix’s subsequent Dragon Quest sequels and Square’s first Final Fantasy would cement medieval fantasy as the “default” for the burgeoning JRPG genre.

These games also varied wildly in graphical presentation. While Dragon Quest and Scheherazade were top-down overworlds, Digital Devil Story was a first-person dungeon crawler, and Phantasy Star combined the two. The first- person perspective was favoured for combat, especially turn-based combat, until Final Fantasy introduced a side-on perspective that became prevalent in the SNES era. Character progression was similarly unstable – while Dragon Quest stuck to the standard stats-gained-via-level-up, Final Fantasy II would experiment with a Stat-EXP system where characters got stronger at certain tasks based on what they did in battle. Digital Devil Story pioneered the monster collector subgenre (a very long time before Pokémon) but emphasised fusing or discarding monsters that couldn’t keep up with the strength level of each subsequent area.

It’s telling that each game released in the late 80s and early 90s insisted on adding something to a prior title, whether it was Dragon Quest 2’s party system, Final Fantasy’s job and class systems, or Digital Devil Saga’s monster collecting. Each game had to innovate more than the last, and innovate with mechanics, rather than focus on differentiation via story as happens now. Despite the JRPG being a fundamentally narrative-driven one, back then developers still needed to sort out the “rules” for the genre. And the developers back then were playful! Each game from this early era aimed for its own distinct quirk and flavour, and because none of them yet had a legacy to live up to or nostalgic fans to please, they could instead boldly traverse new and unusual directions in the hope that they would strike gold.

It depends on who you ask, whether this era of the JRPG’s history was more a renaissance or an arms race. Many of the games released in this period are rife with bugs or glitches, imbalanced difficulty and questionable design… likely casualties of making very big games with accelerated production schedules and no meaningful way to patch things. Most infamously, Dragon Quest 2 was rushed to the point that whole areas weren’t tested, leading to difficulty spikes in both combat and exploration (there’s a crucial key item that’s just hidden on a random unmarked overworld tile, for example). A good number of Final Fantasy I’s spells did absolutely nothing, and some jobs had their stat progression bugged to the point of being totally outclassed by others. Playing a game from this era in its original state often involves checking up a fan site just to understand how the game is supposed to work and how to deal with the bits that weren’t working as intended.

It took until the early 90s and the advent of the SNES for JRPG developers to start to form a standard baseline for their experience. Starting with Enix’s Dragon Quest III, which to this day is considered monumentally influential in the genre, the groundwork was set and audiences started to expect a certain polish, routine and user-friendliness to the JRPG. The SNES Final Fantasy entries, Capcom’s emergent Breath of Fire series and the Genesis Phantasy Star genre challenges are all good and comfortable, but by this point, there was a codification coming in and perhaps, with that, a loss of wild creative energy. At least, creative energy around the mechanics.

What followed, in the mid-late 90s, is more universally known as a renaissance. When we think about the masterpieces of the genre, the 90s is where we see the “best of” lists start to lengthen rapidly. So with this in mind, what’s the point of going back to the 80s?

The Magic Of The 80s

I found my answer in Nintendo’s recent Switch Online release of Earthbound Beginnings. This game, originally titled Mother 1, was Shigesato Itoi’s proof of concept of a JRPG set in the modern-day. It never saw release in English despite being fully translated, because it was seen as a risky move that might siphon off sales for Nintendo’s upcoming SNES. So now is one of those rare moments where English-speaking audiences get to experience a historic, early-era JRPG for the first time, as a collective rather than in secluded translation-ROM communities.

Unsurprisingly though, people don’t seem to like it. Mother 1 is archaic – it has all the hallmarks of the NES-era JRPG: long dungeons, only eight inventory slots per character, limited save points, high encounter rates and an unforgiving endgame. Like Dragon Quest 2, it faced a rushed development schedule and no beta-testing. Its plot is bare-bones and told better in the SNES’s Earthbound, which to this day remains one of the most notorious “cult classic” games of all time. Most reviews suggest playing Mother 1 as if it is a de-make of the SNES title, and only if there’s some personal interest in its historical significance.

But I loved Mother 1, and I learned to fall in love with it after remembering my enjoyment of Dragon Quest not in spite of its flaws, but rather through embracing them. The high encounter rates, the confusing dungeon layouts, the inability to reliably run from encounters – these are features. And if you see something as a feature, designed into the game at some point for a specific reason, then it can be engaged with.

Mother 1 often feels like it’s out to bully the player directly. Most areas have enemy mobs that are outright not worth fighting. They damage the player too much to make their low EXP yields worth it, and some of them explode on death and deal massive, unavoidable damage. Dungeons are long and confound players with repeated art assets. New party members start at Level One. A key plot item is hidden in a random cactus in a massive desert. Some NPCs fight the player when talked to, or worse, pass on the flu, which saps health and requires paying a doctor half your life savings to cure it. This is a game that is so cruel that it starts to feel like social commentary.

But for all its unfair di culty, it can be beaten. Grinding is one solution, but another is meeting the game on its own terms – learning what each item and skill does, and making the most of the resources you receive. The final dungeon, reviled by nearly everyone who plays Mother 1, makes perfect sense if you take the time to map it out, and after a couple of journeys through, it will ingrain itself into memory. I know which enemies to hunt and which to avoid. I know what skills to use in what circumstances. I know what to do, where to go, who to talk to, and how strong I’ll need to be before I can tackle the next area. And because I amassed all this expertise, I deserve my victory.

In conclusion, let’s wax philosophical. Was any of this, meaningful? Worthwhile? The hours spent on grinding, the pen and paper maps strewn across my desk, the multiple bookmarks to walkthroughs saved on my browser? Now that the journey’s over, no. It’s not like there’s some prize I win, or even bragging rights. I’m sure there are plenty of JRPG fans, let alone people who look at any game in the genre with a raised eyebrow, who would consider my endeavours completely silly.

But what I do have is a personal sense of achievement, and that is cemented in my memory more vividly than most. There are JRPGs that I think fondly of, yet can remember very few specifics about. Meanwhile, I’m sure I will remember Mother 1 as I remember the original Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy. These are games that made me work for my fun, and as a result, the fun was all the sweeter.

Please Note: This feature was originally published in the Dee Dee Zine. As we are no longer publishing that magazine, we have re-published it here for posterity.

Great article! I find it interesting that it seems when the JRPGs stopped experimenting and started codifying, the opposite was happening in the West branch of the genre. 1990s is when things like Elder Scrolls: Arena, Wizardry 7, Albion and later Fallout and Planescape: Torment came out, mixing and matching genres and themes. It’s also when hack and slash became its own thing; I still remember people arguing if Diablo is an RPG or not. It’s a bit of a shame that both sides seem to have stagnated somewhat and even indies seem more derivative than creative.

Indeed. There is the rare effort to do something innovative (and I think that’s the underlying reason people loved the two NieR games so much), and some indie titles like Cris Tales really do interesting and unexpected things, but you’re right, the genre is existing a little too much in a comfort zone right now.

Really enjoyed the article. I’m playing through DQ 2 on the Switch currently. DQ 1 was my first RPG ever and the one that got me into the genre back in the very late 80s/early 90s. Also one of the very RPGs I ever actually finished along with Ultima IV Quest of the Avatar.

I’d like to say that I’ve never been very good at games (even though I love them) in general but I am surprised when I read or hear about how difficult the games were back in the day. I’m no better now, so many decades later, than I was as a child but I could actually finish games back then sometimes and now a days I have a ridiculous time at it. I don’t think games are easier today. They are certainly different but without guides at certain points, they would be impossible for me to progress in.

I do think that modern games are difficult for different reasons. They’re much more demanding of a player’s mastery of the systems, mechanics, and action, whereas early JRPGs were more a test of people’s patience (to grind) and intellect (to use the combat system well). You’re right that it’s a different kind of difficulty, but the difficulty is there.