I really wonder if there will ever be a time when I don’t leap at a re-release, remaster or remake of any of the first six Final Fantasy games. I already have all of these pixel remasters on my PC, and yet here I am playing them again on the PlayStation. And then I’ll buy them on the Switch too. Am I the problem? Am I part of the reason Square Enix keeps getting away with this rather cynical re-release strategy? Yes. Yes, I am.

Do I care? Frankly, nope. With Final Fantasy, I take a break from anti-capitalism and just let myself enjoy these things.

There’s obviously no point in writing a standard review for this collection. If you’re an existing fan, you already know if you’re going to follow me in giving Square Enix yet more money for yet another version of the same thing. On the other hand, if you’ve somehow avoided these games so far, then I’d be surprised if anything that I could ever write would convince you to actually give them a go. So, instead of a traditional review, I’ll use this digital publishing space to discuss why I believe that every game in the series is still a five-star title, all these years and re-releases later.

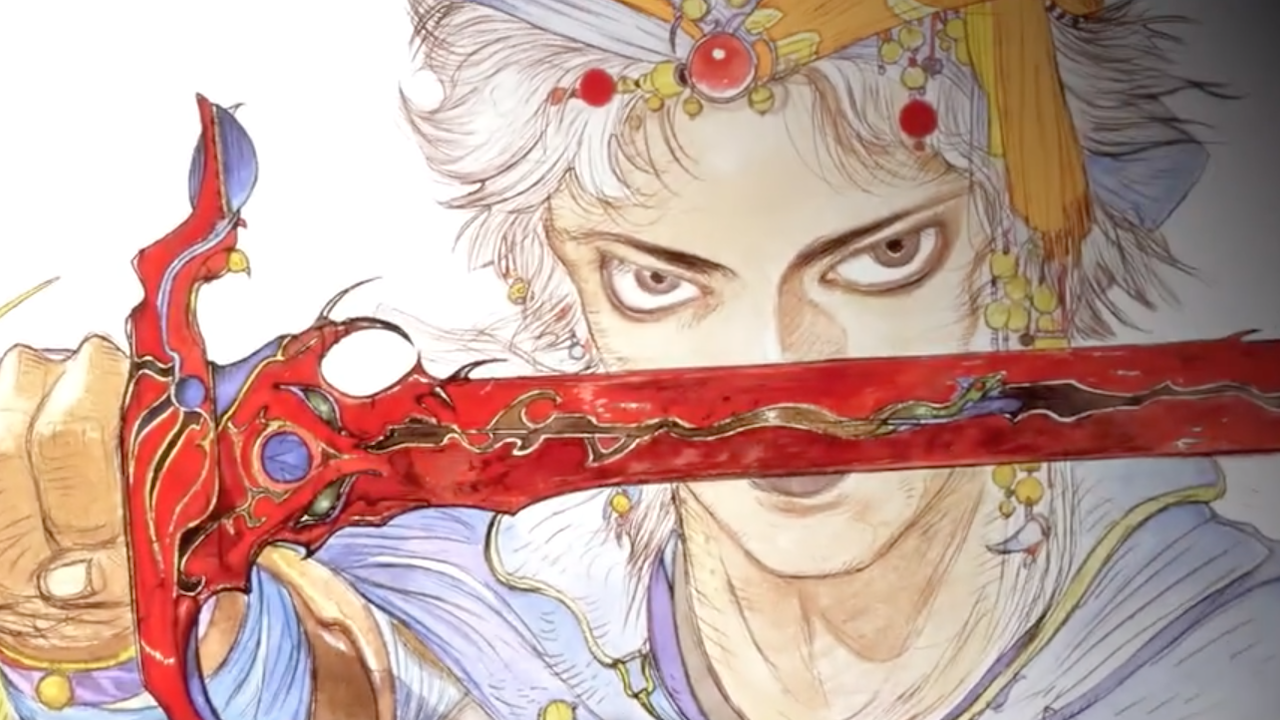

First, though, I will quickly mention that the ports are of excellent quality. In each case, you get the option of a re-orchestrated musical score or the original. Each title also features an extensive gallery of art from the character and concept artist, Yoshitaka Amano, for you to admire. Within each game, there are some simple quality-of-life features, like the ability to turn random encounters off, and there is an alternative to that infamously ugly font that came with the original PC release of the series. In every way, these are the definitive versions of their respective titles (notwithstanding the incredible 3D remakes of Final Fantasy III and IV). Square Enix really has done a bang-up job with them, and as remasters they are also five-star efforts.

Now, with that aside: If the Final Fantasy series wasn’t my very first exposure to JRPGs, it was one of them. Way back when, JRPGs didn’t get released in Australia in large numbers. Indeed I don’t think I ever saw any of this series in stores, let alone the more obscure JRPGs on SNES and earlier. But I was a big Dungeons & Dragons fan. Knowing that, people pointed the Final Fantasy series out to me (remember the days of chat rooms and bulletin boards, fellow Millennials?), so I found… ways… to play them.

I was instantly lost in their magic. There was magnificence about the scale and scope of Final Fantasy and the world (if not universe)-shattering conflicts they depicted. The characters were vivid and detailed, and Square was doing some really creative things to make them memorable. Never before (and not very often after) have I played a game where, for hours, you carefully build up a character, only to be tasked with ascending a mountain, so the character could battle themselves, and emerge “reborn” as a new, weak, level 1 character all over again. That scene alone has so much thematic density that it ensured that Final Fantasy IV’s plot was the closest that video games had come to literature at the time. It offered such complexity that people still write essays about it to this day. At a time when most SNES games barely spat out two lines of dialogue before throwing you into the thick of the action.

Final Fantasy VI’s opera scene was spectacularly ambitious for a SNES game. Final Fantasy V’s job system remains a delightfully intricate and interesting mechanical approach to levelling to this day. And then through Final Fantasy I and III we can see how Square slowly built the ethos of the series, to become something as iconic as it is today. Each game in the series has some kind of quality about it that makes every subsequent replay an opportunity to discover something new, or think about events in a different way. To this day I find new little things to appreciate about these games every time I replay them, and while I rarely find a modern game I want to play even a second time, with these six titles I do wonder if I’ll ever actually reach the point that they fail to delight me.

Related reading: The ten finest Final Fantasy songs of all time.

These days, what happens far too often in video games is that developers first focus on building engines, deciding on the art direction, and finding the gameplay mechanics from other games that they like and want to clone. The narrative becomes something that they squeeze around the game that they’re building. While it’s understandable from a project management point of view, it’s a lousy way to approach narrative experiences, and that’s why so few modern games are able to break beyond very rote, very standard narratives. If you’ve already got the model kit, there’s only so much customisation you can do.

But you can be sure that Cecil’s transformation in Final Fantasy IV was a pivotal moment and the game itself was built around it. You can be sure that the complex way players move between characters in Final Fantasy VI was already planned out from the earliest stages. Yoshitaka Amano’s art, which the development teams then needed to convert into 8-bit or 16-bit sprites, all ensured that the narrative and fantasy of the experience was central to the project.

I often wonder how players would cope with these early Final Fantasy games if they played them for the first time today. Given the way that the Square Enix producers talk about action combat being here to stay, you’d have to think that Square itself assumes that players will find turn-based action archaic and difficult to get into. Perhaps that is the case. Perhaps we’ve already hit the point where the first few Final Fantasy titles have an audience similar to the people that still watch Charlie Chaplin and Humphrey Bogart films of the black & white era. Perhaps they are works that are only beloved by the shrinking pool of people that remember a time when content was art.

However, the 8-bit and 16-bit Final Fantasy trilogies are both genuine masterpieces. These games wove deep, compelling stories that were as thought-provoking and artful as they were entertaining. Back in the day, they were a promise of what video games could be, and what people had to look forward to as the medium emerged as an art form. Increasingly, they’re a sad statement for what games could have been, had the medium not shifted to a pastiche of Hollywood excesses.

Dear Matt S. It was your final sentence in this review, found truncated on Meteoritic, that got me to click through to your website. You write with thought and skill. Bravo.