There’s no way I can start this article without acknowledging that professional wrestling, the one “sport” that I properly follow, is a staged performance. “Fake” is often thrown around, but that’s not entirely accurate when you’re talking about a performance that can involve being thrown off a ladder through a flaming table that’s also covered in thumbtacks. That’s going to hurt, no matter how much the end result might be predetermined.

Pro Wrestling is dominated by US-based promotions, most notably WWE, or World Wrestling Entertainment in most people’s imagination.

Look outside the USA, however, and the next biggest wrestling market is Japan, home to promotions both major and minor and a highly dedicated fanbase. The Japanese also love their wrestling games, and have a long history of making some of the best of them.

It’s actually remarkable that while Japan plays second fiddle to the USA in terms of global wrestling reach, for decades now, the very best, most creative, and most fundamentally interesting wrestling games have come from Japanese game developers. It’s not even a close-run race, with American-developed wrestling games all too often falling short of the simple mark of being playable, let alone fun.

While there’s a degree of development skill at play here, I think there’s also another factor that leads to the superiority of Japanese wrestling games. That’s the culturally different way that pro wrestling is viewed in Japan.

US wrestling is all bombastic spectacle and high-end drama, with larger-than-life “Superstars” – and that’s the term that the WWE uses – to wow the crowds.

Japanese wrestling has its share of that kind of approach, because there’s a promotion for every niche, whether it’s the big leagues of New Japan Pro Wrestling or the more directly parodying- WWE style of DDT Pro Wrestling.

However, Japanese Pro Wrestling is generally a lot more respected as a performance sport than its western counterpart.

To give a non-video games example, in the West, when Jesse Ventura won the governorship of Minnesota in 1998, it was treated more like a joke than anything else. Depending on your politics that description might be quite appropriate, of course.

In Japan there have been numerous wrestlers to gain political office, including legends such as the recently deceased Antonio Inoki and Hiroshi Hase.

While he wasn’t always successful, Inoki-san seriously worked to try to repair the relationship between Japan and North Korea over the years, largely inspired by his pro wrestling mentor, the legendary Rikidōzan.

Admittedly, Inoki-san did also once ask the defence forces how they’d deal with an alien attack in parliament, which sounds suitably pro wrestling wacky. Even there it was a smart approach because it allowed them to answer the question around an invasion without specifically mentioning a real-world potential foe such as China or Russia.

Hase-San has held office for decades now, and recently deceased Japanese PM Shinzo Abe even named him to his cabinet. That’s not a move you make for some muscle head just because he’s popular.

If politics doesn’t float your boat but video game developers do, how about Goichi Suda? In an interview some years back, he told DDNet editor Matt that he only turned to game development because he wasn’t able to get a career working for one of Japan’s very popular pro wrestling magazines.

Part of the reason why the cultural impact plays into how Japanese wrestling games have been developed is because the sport aspect is generally prioritised in Japanese wrestling. There’s more of a focus on the “wrestling” part of the equation as distinct from the entertainment side, and that’s long been the case.

For a traditional Western pro wrestling audience, a match is as much about the flashy entrance, the lengthy promo and the drama of the stakes in the match.

This can vary from the simple – say, fighting for a championship belt – to the downright wacky, such as fighting over a shampoo commercial. Yes, that’s a real WWE storyline, involving two former WWE champions at Wrestlemania, no less.

Japanese wrestling has elements of this – and there are promotions that use that style to an extent – but it’s typically so much more about the in-ring action and a logical sequence of moves that lead up to a satisfying finish. It’s viewed as a sport first, entertainment second, and that’s an approach that lends itself very well to video game design and implementation.

You still get stars with their signature finishing moves, but they’re not the game-ending spectacles they are in the Western world. Hit your finisher in a Western wrestling game and it’s typically game over, which is why those games are nearly always built around building up a special meter to allow you to do just that, typically one time to finish the match. It’s the equivalent of one of Mortal Kombat’s fatalities in that sense.

Hit your finisher in the opening minutes of a Japanese game (or real-world Japanese match) and it will have impact, but your foe will kick out, because you simply haven’t worn them down enough.

That led rather quickly to Japanese action-based wrestling games focusing on more of a simulation style rather than just a simple bombastic presentation. For western games, it may have been enough to have a honking big picture of Hulk Hogan on the cover of a game, but Japanese wrestling games sought to do much more from an early stage.

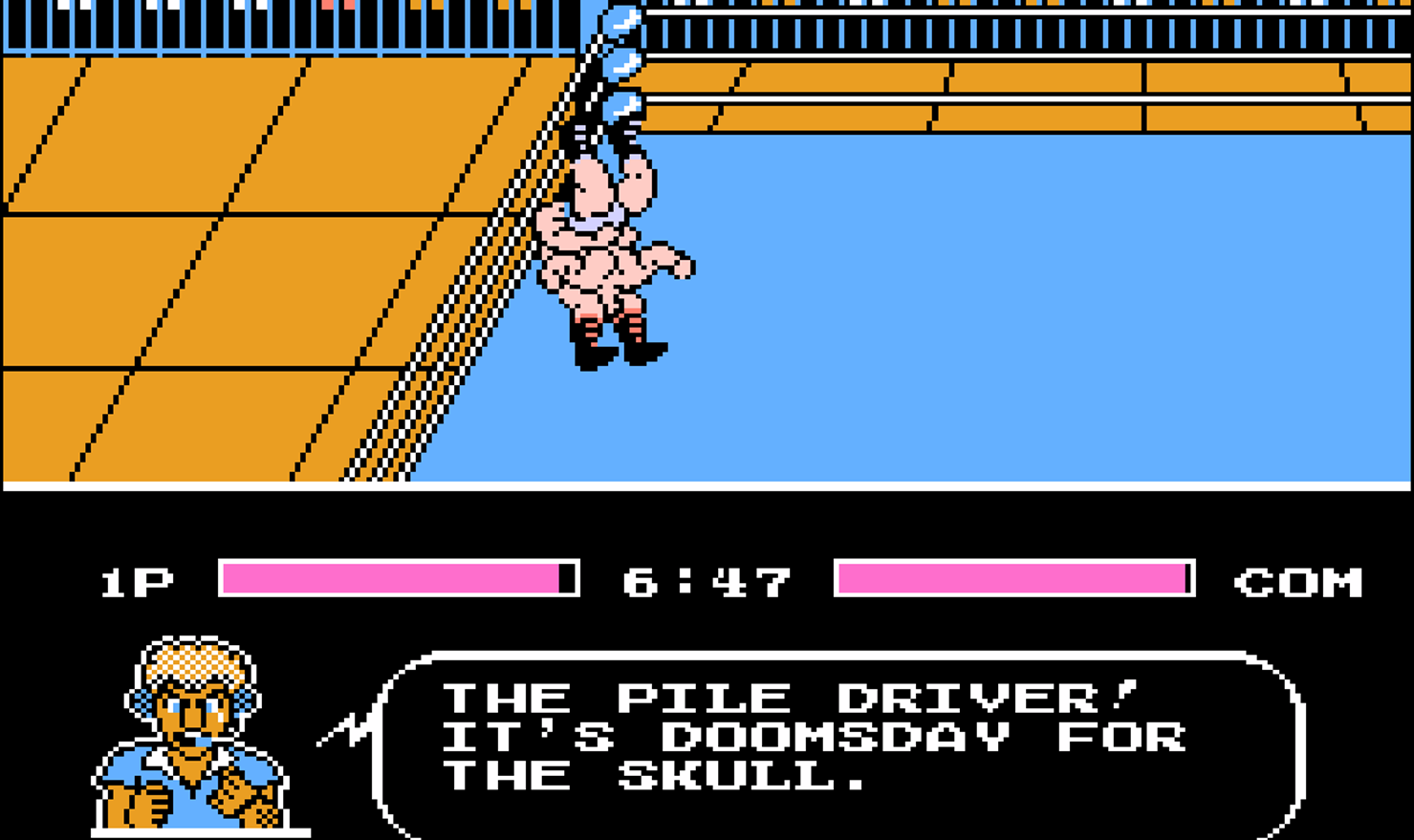

It’s something I now find genuinely infuriating, because having gotten into pro wrestling games in the early 1990s, we were stuck with lousy LJN or Acclaim WWF games with terrible controls and a focus on arcade-style gaming.

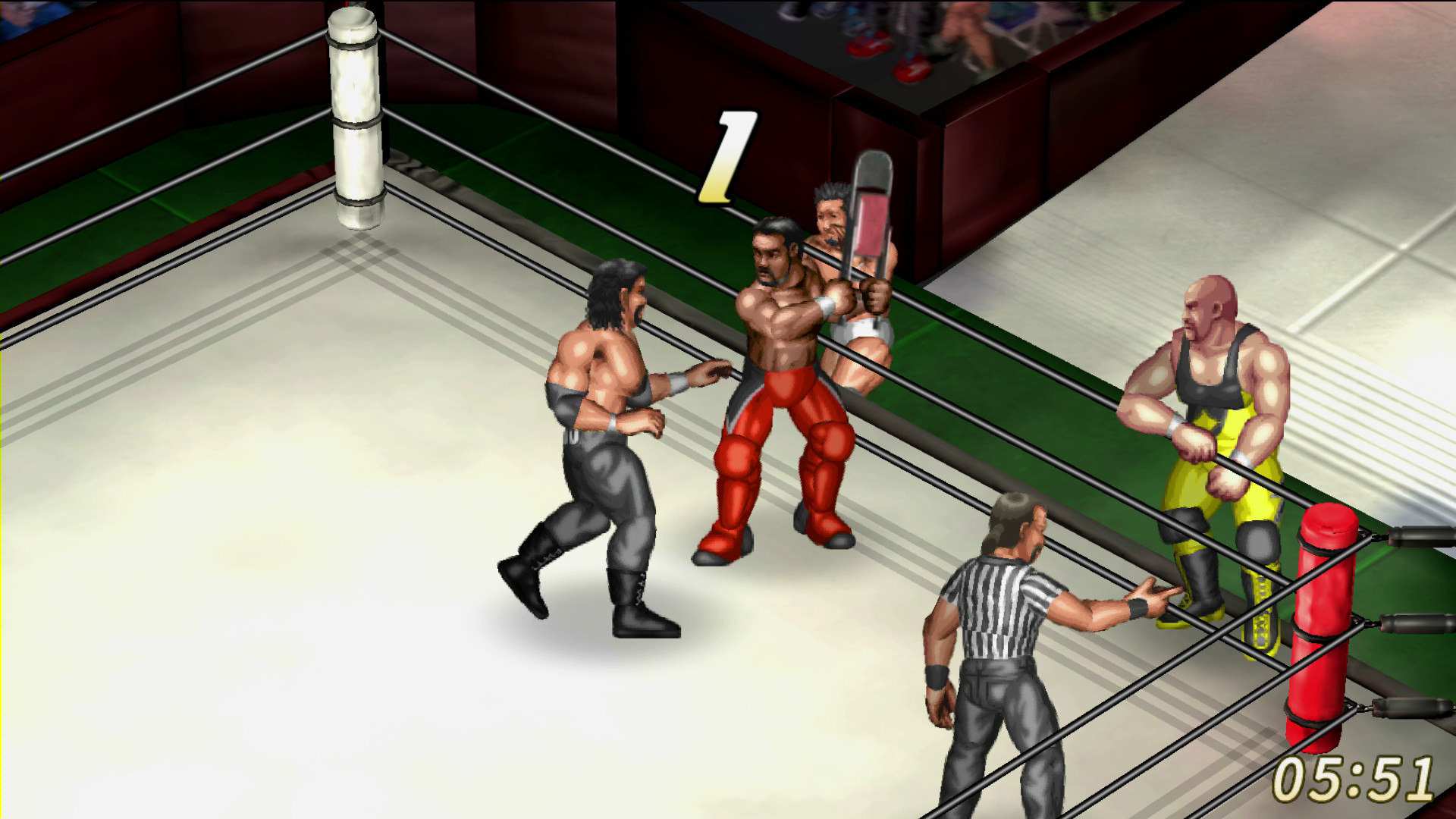

Meanwhile Japanese gamers had a rich diet of wrestling gaming choices, headed up by the legendary Fire Pro Wrestling series. Fire Pro spawned many imitators that aped its close simulation style, but the story of Japanese wrestling games doesn’t end there.

The respect shown to pro wrestling in Japan also gave developers a lot more freedom to explore alternative game ideas, not just straight-up combat-centric titles. Frankly, the sheer variety of Japanese wrestling games over the years is staggering.

Want a wrestling RPG? There’s Monster Pro Wrestling, or one of the side stories in Live a Live to choose from.

Visual Novels more your style? Toukon Heat or Shiroi Ringu He has you covered.

Prefer trivia games? Pro Wrestling Kentei DS is for you.

Prefer women’s wrestling without the bra and panties or chocolate mud pool wrestling nonsense that dominated WWE’s thinking for many years? Fire Pro Joshi All-Star Dream Slam combines the technical wrestling aspects of the classic Fire Pro series with an expansive roster of legendary joshi wrestlers. Or there’s Konami’s Rumble Roses if you really must go down the cleavage route with a side order of German suplexes.

Speaking of women’s wrestling, WWE won plaudits for putting Becky Lynch on the cover of a wrestling game for 2019’s WWE 2K20 as a long overdue progressive move. That’s true enough, and a fine achievement for Ms. Lynch, but Cutie Suzuki beat you to it by some 29 years with Cutie Suzuki’s Ringside Angel.

Within Japanese wrestling matches themselves, you’ll often hear reference to “fighting spirit”, or the idea that a wrestler might gain a last-minute, desperate burst of energy in order to finish off their opponent.

Fighting spirit was born out of the concept that matches are about wearing down your opponent, not just hitting that one flashy finishing move to end a match quickly. Culturally speaking, Japanese Pro wrestlers are warriors, and a warrior’s spirit would not simply allow them to accept simple defeat.

That fighting spirit concept works wonderfully for a wrestling game of course, because it’s exactly the same kind of idea that lies behind the super meter in most traditional 2D fighting games, especially those that trade risk and reward for building up a better special move.

There’s little that can compare winning a brutally hard-fought Fire Pro bout where you’ve both pummelled each other with countless heavy moves, only to finally best your exhausted opponent.

How much better are and were Japanese developers at bringing the world of pro wrestling to games systems? I can think of no finer argument than the fact that once you get to the PlayStation 2 era, even the games built around Western wrestling companies – again, most notably WWE – were being built by Japanese studios.

For years, Osaka’s Yuke’s Co had been developing its Toukon Retsuden games around New Japan Pro Wrestling, but it’s the same engine that WWE turned to for its Smackdown! Games that later became the yearly WWE titles up until 2018.

So what happened in 2019? Take Two, who by then held the WWE licence, decided that its own Visual Concepts studio could handle all the development by itself, having worked with Yuke’s for the past few WWE games. To be fair to Visual Concepts, it was reportedly dumped into that arrangement with limited development time, which did play a part in the “finished” product.

To call the results disastrous would be kind. Look up WWE 2K20 glitches on YouTube, and when you’re done with either laughing or dropping your jaw at just how bad that game was, you’ll appreciate what decades of experience and appropriate approaches have done for making Japanese wrestling game developers the world’s best.

The WWE games have recovered a lot since 2K20 to be fair, but notably, when relatively new US promotion AEW decided it wanted to put out a video game, it engaged Hideyuki Iwashita, director of the classic AKI N64 games, along with Yuke’s to actually develop it.

We’ll have to wait until 2023 to see how that particular fusion of Western style and Japanese development ideas actually meshes, but AEW’s repeatedly invoked the classic AKI No Mercy/Virtual Pro Wrestling games when talking about the game, so there’s plenty of scope for a best of both worlds situation there.

Recent years have seen the pace of Japanese-only wrestling games development slow rather markedly, although the expansion of key promotion NJPW into Western markets – they’ve even run Australian tours – does raise the prospect of getting even more options and excellent wrestling games in the future.

Note: This article was first published in the November 2022 edition of the Dee Dee Zine. As we are no longer publishing that magazine, we have re-printed this article here for your reading pleasure.