Finally. We have finally had the chance to play Project Zero: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse. A game that was previously exclusive to the Nintendo Wii in Japan is now available on just about everything and globally, in English, for the first time. I won’t say it was “worth the wait”, because we should have never had to wait for it in the first place. It’s a masterpiece and it was silly not to localise it on the Wii. I am glad Koei Tecmo finally realised that, though.

Mask of the Lunar Eclipse is very much in the vision of the rest of the series. Principally, you’ll be playing as one of several absolutely beautiful women (and the very rare, yet equally beautiful man) as they explore very Japanese haunted locations, fending off attacking ghosts as they try to get to the bottom of mysteries such as the truth behind ancient, horrible rituals and why their friends are all dying around them. It’s a very different kind of horror from what people weaned on Silent Hill and Resident Evil might expect from Japanese developers. Also, unlike Silent Hill and Resident Evil, Project Zero is genuine Japanese horror. It’s different – where the development teams at Capcom and Konami have found greater success globally thanks to their horror aping the western and Hollywood approach, Project Zero has and will forever be niche – but in exchange, it also has a greater cultural resonance and authenticity to it.

The difference is nicely summarised by Takashi Shimizu, one of the most accomplished Japanese horror filmmakers and thinkers (the mind behind The Grudge). In an interview, he defined the difference as such:

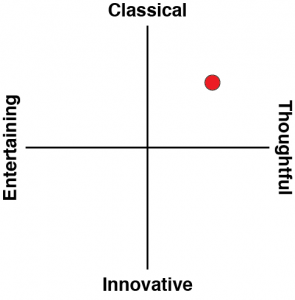

“After releasing Juon in Japan in 2002, I worked on the Hollywood remake The GRUDGE and the sequel The GRUDGE 2, and through these experiences I started to understand the difference between fear in Japan and fear in America. When it comes to horror, no matter what country, it’s a genre that creates entertainment from fear. However, the portrayal of that fear varies differently depending on if it’s “scary” fear or “surprising” fear. The culture and social climate of the countries are where I feel America and Japan differ the most.

“In basic terms, American audiences tend to prefer “surprising” fear that makes them jump out of their seats. And after being scared, the audience often bursts our in laughter. It’s kind of similar to riding a roller coaster; they like to enjoy a physical sense of fear. Especially with the traditional American tradition of Halloween, there is a tendency to “enjoy” or “have fun” with fear in America. From kids to adults, everyone understands that Halloween is a world of fantasy, allowing them to truly enjoy themselves on a societal level. This is why most American’s burst out laughing after being surprised with a scary experience.

“A Japanese person who has been living in America told me that although he used to be scared of traditional Japanese ghost stories, after spending a long time in America and getting used to the culture and traditions, the Hollywood-style of horror has become more effective at portraying fear in a direct fashion. Basically, he said there is more reality to be felt from the type of horror that is based on “logic-defying beings attacking people with evil intentions”. This is why Hollywood-style horror is based in the direct sense of physical fear that comes from the idea of being attacked, eaten, or killed by various creatures and monsters. This type of fear, which could be labeled as masculine fear, comes from the real fear humans feel when we sense physical danger and is a fear that transcends cultural barriers. Thinking about it, for a multi-cultural country like America, this type of fear is what should be expected.

“On the other hand, Japanese audiences prefer the “scary” type of fear that affects them indirectly and psychologically. This is the type of fear that quietly builds up, creating an impending sense of intangible doom. Many Japanese people feel that the image of a ghost just standing nearby, doing nothing, is much more fear-inducing than other images.”

(Apologies for the extended quotation, but all of this is very relevant).

To greatly paraphrase in summary, western horror tends to be about a physical existential threat – there are big, horrible, ugly monsters that are out to get you, and they’ll jump at you, triggering your fight-or-flight response, and then you’ll do battle with them. Japanese horror, meanwhile, is more psychological. It’s about intense tragedy and its implications for the mind and soul. It’s about unease building, and building, and building, until the revelations crystallise and finally having the knowledge leaves you shaken to your core. When I think about Japanese horror, I rarely remember being “terrified”, or even shocked. Instead, I remember overwhelming sadness and a deep sense of unease about what led to the nightmare occurring. The Japanese The Ring was provocative and effective horror because what happened to the poor girl, Sadako, was both a cruelty and a tragedy. It was not horrific because she started crawling out of TVs and murdering teenagers (as per the dismal American demake).

With all of that as a kind of thematic background, Mask of the Lunar Eclipse is an expert example of Japanese horror. Players might at first be put off by the glacial slowness that the characters walk (or even run), or the way that individual battles with ghosts tend to drag on for a while – this isn’t a game where you’re going to be ducking and diving and firing off headshots like you’re in an action film. There is plenty of combat, of course, but I would be more inclined to compare Project Zero to the point-and-click adventure game genre than anything to do with action genres. Cut scenes and story fragments are also vague to the point of being frustratingly obtuse at first. But as you continue to play, the rhythm of the game becomes more apparent and the purpose and story becomes clearer. Essentially, Mask of the Lunar Eclipse builds, and builds and builds. Layer after layer of tragedies turned into nightmares. Wailing ghosts rather than hulky monsters to tear into gory masses. It’ll take you around 16 hours to complete, and not a moment of that feels wasted. Painstakingly deliberate, yes. Almost glacially slow at times, absolutely. But the atmosphere is almost choking, and you’ll not soon forget the revelations that this game hits you with.

The other hugely effective horror trick that the Project Zero series has always had going for it – and Mask of the Lunar Eclipse is a masterful example of – is the way that you need to stare a ghost in the face and let it approach you when fighting it. You only really have two offensive weapons in Mask of the Lunar Eclipse. One is the series’ iconic Camera Obscura, which allows you to damage ghosts by taking photos of them, and there’s also a Spirit Torch that collects and channels moonlight into a beam that can harm ghosts. In both cases, while “ammunition” is plentiful, you’re better off waiting for the enemy spirit to get as close as possible. With the Camera, it’s because it takes a while to properly focus and will cause more damage if the spirit is close. With the Torch, the amount of energy charge available is limited so you’ll want to make the most of it to avoid running out. In both cases you’re going to spend time watching the spirits approach you, deliberately suppressing both fight and flight impulses as you do so. The amount of waiting involved does have the effect of making combat much slower-paced than other modern horror games, but also, in my view, far more effective. Resident Evil Village was a very fine game, but let’s face it, it was a horror-themed action game. For, better or for worse Mask of the Lunar Eclipse emphasises a truer kind of horror.

In some ways, I felt that despite being a remake this game does show its age when compared to Maiden of Blackwater, the most recent Project Zero, developed for Wii U before being re-released on all platforms a couple of years ago. Controlling your protagonist is slightly clumsier than it should be, for one thing. While I never played the thing on Wii I do think this is a consequence of the Wiimote being used with motion controls originally, and now it’s all mapped to a standard controller. Even a couple of hours in I still found myself accidentally spinning my character around when I was simply trying to point the torch at something. It was rarely deadly because of the game’s methodical pacing, but it did disrupt the careful control the developers otherwise placed over the experience – i.e. my suspension of disbelief was momentarily disrupted by my character doing weird things.

While it perhaps doesn’t “play” modern enough, the remake is in every other way perfect. If I didn’t know that this was based on a Wii game, I would have been surprised to find that out. The character models in Mask of the Lunar Eclipse are absolutely incredible in their level of detail and animation quality, and the environments are drenched in atmosphere. There’s a darkly ethereal and dreamlike quality to the presentation, where movement almost seems to be like pushing through water. Again, while it does take some adjusting to get used to this almost unique aesthetic direction the developers have taken, it has real stylistic impact once you’ve settled into the rhythm. The levels themselves are, perhaps, a little smaller than we might expect from a truly modern game, but because you’re given plenty of time to drink in the atmosphere as you explore, and there’s quite a lot of backtracking involved thanks to traditional horror-style puzzles and progression systems (i.e. you’re spending a lot of time finding keys to unlock doors on the other side of the map), the levels still feel large enough and fit for purpose.

Besides, the Project Zero series has always been inspired by haunted houses, which are still a major part of Japanese entertainment and a summer seasonal activity that horror fans across the country look forward to each year. Haunted houses aren’t big spaces. What they are is intense. Similarly, while I’ve been talking about “slow pacing” throughout, the way the game builds means that you are in a constant state of heightened anticipation as you play. While the game isn’t big on jump scares, you are going to be sweating over your controller anticipating something every time you turn a corner or open a door. Perhaps moreso than any other game in the entire series, Mask of the Lunar Eclipse comes across as confident. Like it has carefully measured every microsecond throughout and is delivering exactly what it wants to. Perhaps that has to do with the involvement of Goichi Suda’s Grasshopper Manufacture in the production of the game, and it’s subtle, but the razor-focus on the experience this time around is impressive.

The only time the developers allow themselves to break the taut experience is via the bonus costumes. All of these are silly, of course, and generally atmosphere-destroying, but they’re all totally optional, and I’d be lying if that wasn’t a compromise I was willing to make for the swimsuits on my second play-through. Project Zero has always been about beautiful horror, after all.

Project Zero: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse is by no means a mainstream horror game, is the point that I’m making through this review. However, it is incredible. In the context of the broader Project Zero series, it’s going to be fondly remembered. It’s hard to look past Project Zero 2 as the masterpiece of the series, but the intensity of the atmosphere and strength of the narrative in this one means that this one isn’t far behind. More importantly, however, is that in 2023 this is one of those surprisingly rare attempts at a Japanese horror game, as opposed to a horror game made by Japanese developers. They’re different things, and this game is not only an excellent piece of entertainment, but it is also an enormously useful resource for anyone that wants to understand the aesthetics of horror outside of the western mainstream.