Note: This article was originally published in the October 2021 edition of the Dee Dee Zine. As we have ceased production of that magazine, and school settings are relevant this week courtesy of the release of Persona 3 & 4 on Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4 & 5 and Xbox Series, we are re-printing it here.

“When you ask me why I tend to draw school uniforms as a motif, it’s because it’s something that a lot of people can share. There’s something very familiar about it,” Mel Kishida, the character artist behind the Blue Reflection series, said. “For people who grew up in Japan, like I have, and spent their school years in Japan, many of them will have memories in which students in uniforms are part of the visual memory.

“You’ll remember that you had a crush on a girl or something like that, and with that memory comes the memory of the uniform that they wore. So it’s not so much the uniform in itself, and I don’t draw it because I have any particular aesthetic interest in uniforms, but it’s because it calls back memories, and has a strong resonance with a lot of people that view my art. It helps people remember and relive those experiences they had in their youth.

“Blue Reflection was very much made with that thinking in mind, of conjuring up memories of what it’s like being in school, and the activities and dramas that came with that experience. It’s not so much the outfit itself, but it’s more of what it represents.”

I was fortunate to be able to interview Kishida a few years ago, in a roundtable that was organised to give journalists the opportunity to discuss Blue Reflection 2 with the creative voice behind it. The school setting and schoolgirl protagonists became a central point of discussion, because both Blue Reflection and its sequel are set almost entirely in schools, and even outside of these games, Kishida habitually draws girls in school uniforms. In the anime and video game space this is, of course, very common.

But it can also be uncomfortable for western audiences, particularly when combined with what they view as fan service or “sexualisation.” It’s often not the intent, and Kishida’s Blue Reflection is a particularly good example of that discontent. Blue Reflection itself was loudly criticised for this, but that was not the intent of the art, nor an accurate reading of the game in a Japanese context.

Nostalgia is a powerful drug

Interestingly, Koshida’s comments closely parallel the thoughts of the CEO of Inti Creates, Aizu Takuya, when I spoke to him at Tokyo Game Show back in 2017. Takuya and I were talking about the Gal*Gun series then, and that couldn’t be more different to Blue Reflection – Gal*Gun is deliberately and openly indulging both fan service and sexualisation – but the underlying reason for the school setting is the same:

“When the concept of Gal*Gun was created and the game first went into development, the international market wasn’t thought of at all. This game was made by Japanese creators for the Japanese market,” Aizu said. “There are so many stories in anime and manga set in school grounds that it’s an instantly recognisable setting. It’s also something that all Japanese players will be familiar with, as we all spend many years at school, which have a distinct aesthetic in Japan.”

So, whether the setting is there to play out a warm, romantic kind of ethereal nostalgia, such as in Blue Reflection, or go all-in with the humour and satire to leverage the school setting for comedic effect, as in Gal*Gun, the school setting is a versatile one precisely because it is a familiar, grounded location that players don’t need to have explained to them to understand and immediately connect with.

It’s also worth noting that the coming-of-age story remains a popular, well-trodden one in Japanese video games. It’s not something that we see as much in the west (because western developers are more interested in power fantasies), but coming of age stories and school settings make a natural partnership.

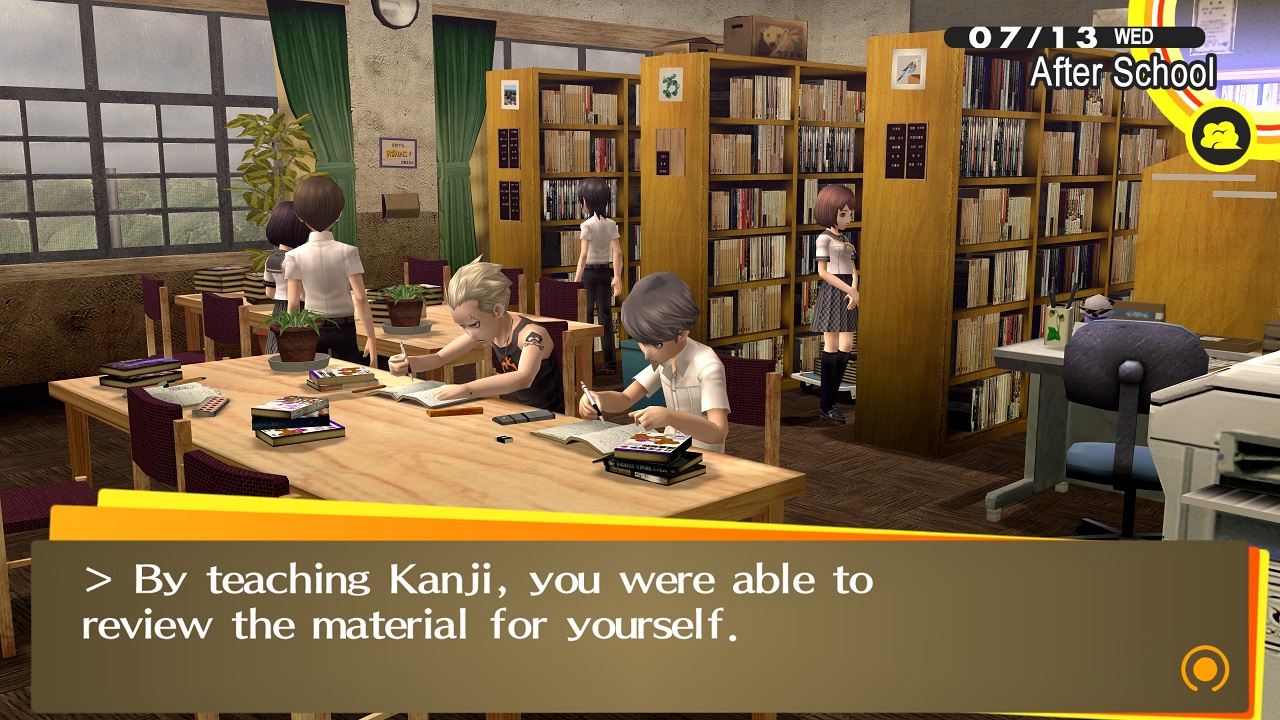

From Persona to Blue Reflection, Lollipop Chainsaw to Gal*Gun, the parallels between how characters grow as people (including the mistakes they make and the personal demons they face and need to overcome), fit beautifully with the journey of growth in skill and expertise that a player has with the game’s mechanics and systems, so the school setting becomes a highly convenient location to contextualise these journeys, and link gameplay and narrative themes together.

Perhaps no better example of this link between “coming of age” and school as a motif for that can be seen in the PlayStation 2 classic, Clock Tower 3. There, the game doesn’t take place in a school, but the protagonist, Alyssa, wears a uniform for much of her journey, as she’s chased around and largely defenceless against the serial killers that stalk her. When she gets the chance to fight back, however, she transforms into a costume reminiscent of a Greek goddess, and this is because she has obtained the knowledge – and growth – that she needs to be able to break away from her youth and become an empowered individual.

And then there are times to subvert

Meanwhile, The Caligula Effect might be a series that is just two titles old at this point, but it has already done a brilliant job in showing how the school setting, and the reason that it draws so many artists to it, can be subverted and challenged.

In The Caligula Effect, people in the real world with massive problems are “captured” by virtual idols (effectively representing Hatsune Miku), and dropped into a fantasy world that they perceive to be real, but they no longer have the problems that plagued them in life. This utopia ages them transformed into schoolboys and girls (regardless of their actual age), and centres the world on school environments.

In other words, just as many Japanese people see stories in school settings as a nostalgic fantasy escape from the challenges of everyday life as an adult in that country, The Caligula Effect makes the fantasy literal for its characters. It then proceeds to dismantle the idea that any of this is a utopia at all, and these illusionary escapes, if they become too overpowering, can start to erode a person’s sense of self.

Another example of the subversion of the school setting is the way it’s a common location for horror within games, anime and film. Japan is suffering a low birth rate and population decline, and this is resulting in schools being abandoned and falling into disrepair. A little like abandoned mental asylums to western horror, this has made the school setting in games like Death Mark an opportunity to invert the innocence and joy the Japanese typically associate with school settings.

Japanese people spend a lot of time at school, and extra-curricular activities with classmates are typical. Furthermore, Japanese schools are a much more social and interactive environment than we typically understand them to be in the west.

As an OECD report on the success of the Japanese schooling system notes: “Time is an important factor in the good academic performance of Japanese students. Until recently, Japanese children went to public school six days a week. In addition, Japanese school children have several hours of homework a day. They have six weeks of vacation during the summer, which is less than students in many other parts of the world. Students often do their own research during vacations. The majority of Japanese students also spend considerable time in various forms of private instruction after the regular school day. These private schools range from offering help to students who are behind to catch up, to offering more advanced study than is available in the public school, to offering extracurricular activities or one-to-one or small group tutoring for some combination of these purposes.

“However, it is not all work and no play for Japanese students. Not all these extra hours are for instruction. Observers believe that one reason Japanese students seem more engaged when they are in class than students in many other countries is that they are given more breaks from instruction. Several times a day, students go outdoors, play, do exercises and let off plenty of steam.”

What this means is that for the typical Japanese person, school is a period of profound growth. Schooling is more than a place to study and make temporary bonds before moving on to college and adult life, and whether it’s the social interactions, the school lunches (there are now entire restaurants dedicated to giving people nostalgia for school meals), or, yes, the school uniforms and crushes, school, to the Japanese, is frequently a nostalgic fantasy with an impact that eludes most of our understanding here in the west. It’s not inherently about the “fan service,” though that may be present. Rather, in studying this material, we have the opportunity to learn about something that cuts to the core of Japanese identity.