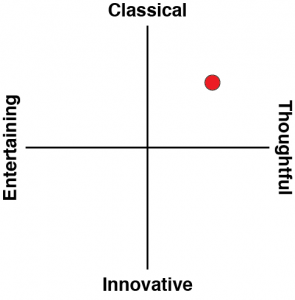

Wayward Strand is such an odd little game, but that is by no means a criticism. Despite its utterly fantastic concept, and ironically given that it takes place in a floating airship, this game is sweet, meditative, and very grounded. It’s also incredibly Australian, but not in the over-the-top, Crocodile Dundee way. It’s authentically, honestly Australian, and we need more of this from the local industry.

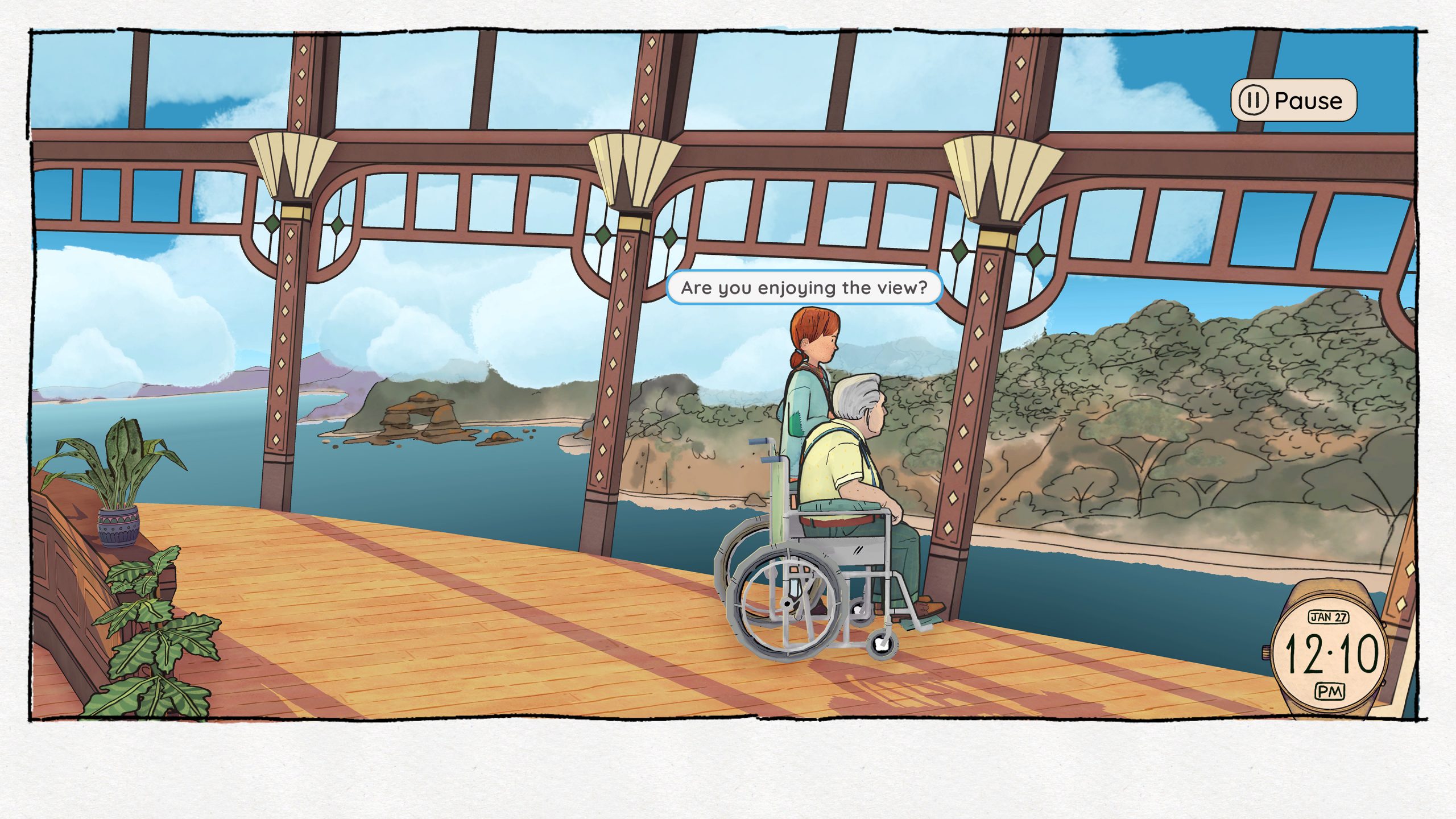

There’s a giant airship that has been anchored to a small town in rural Australia, and it has been pressed into service as a hospital and residence for the elderly. Why? The game isn’t entirely clear on that at first, but you’ll have the vague impression that its to distance the elderly from the rest of society, and that’s certainly a theme and failing of how we treat people in this country. It’s not on-the-nose about it but it does encourage you to think about the implications as the story gets going.

You play as the daughter of the head nurse, who has found herself volunteering to help out for a few days. She does have an ulterior motive, though – she’s also a journalist for her school newspaper, and wants to find out some interesting stories from the residents of the hospital. What this narrative set-up translates to is a simple point-and-click adventure, where you move from location to location, chatting to the residents, and slowly piecing together each story from the hints that others give you.

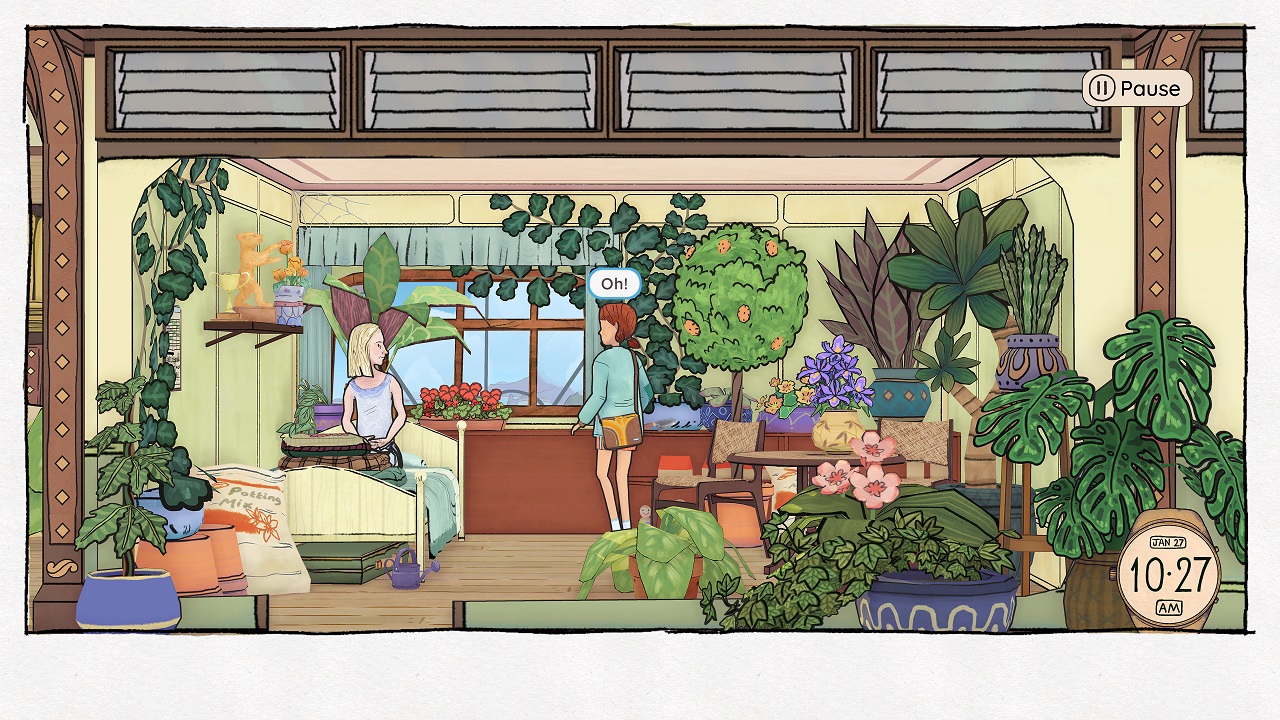

It’s neither challenging nor stressful, but there is a time clock ticking away, and each resident has their own routines that they follow. At lunch time they’ll be found in the dining car. At other times they’ll have appointments with the nurse. Sometimes they go to chat to one another, and at other times they entertain themselves in their rooms.

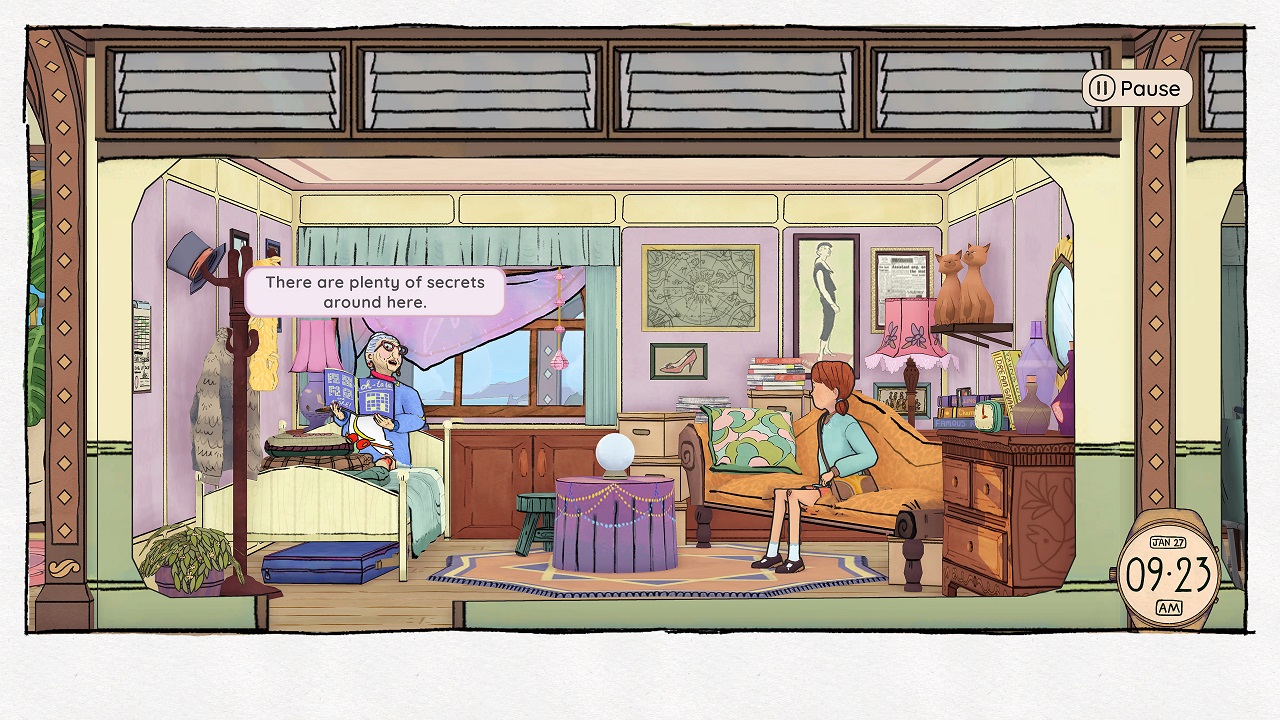

Each character is wonderfully-written, with plenty of nuance and layers of depth that you’ll slowly unpeel as you get to know their history (and given their advanced ages they have a lot of that to share!). At other times you’ll need to find our tidbits of information by listening in to conversations that you aren’t a part of. You can do that by “sneaking” up to a door and listening carefully. No one seems to think to close their doors in Wayward Strand, and there some secrets to uncover. It might not be Hercule Poirot on the Orient Express, but you are do get to play at investigator, and that’s a delight.

With that being said, the stories can also be touching and sad, and some of the characters on the floating boat aren’t all that eager to share them. There’s also a “VIP” visit planned for the end of the week, which gives you a hard deadline to learn as much as you can before their arrival disrupts everything.

What I loved about this is how non-linear the approach to storytelling was. You’re not given a trail of breadcrumbs to follow. There isn’t any bright flashing “objective” icons on the map. Rather, you do get to play journalist, by consulting your notes from prior conversations and other sources of information, and using that information to inform a new line of questioning the next time you meet a character.

This structure gives the game an organic, naturalistic feel that is so uncommon for an industry that likes to lead players through by the nose. A limited number of characters and narrative pathways helps to prevent the non-linear approach to storytelling from becoming overwhelming, and it’s going to be a rare occasion where you simply have no idea of what you can do next.

Backing the warming, wholesome storytelling is some beautiful picture book-like aesthetics. The developers of Wayward Strand have gone for a deliberately low-poly approach that allows them to draw the eye to particular details – such as the adorable yellow-crested cockatoo jumper that one character is wearing – while also papering over details that are largely unimportant. The focus of the game is, after all, on the storytelling. The art aesthetics are in service of that by subtly reinforcing the things that build character and personality.

The game takes place in a lofty, airborne facility, but the stories that it shares are grounded and honest. Wayward Strand is a mature work of narrative, and belongs to a similar Australian tradition as the likes of the classic novel, Storm Boy. Australian writers tend to be at their best when their stories express a simple honesty about humanity, and while that can be taken in some extremely brutal directions (think Mad Max or Nick Cave’s And The Ass Saw The Angel), it can also be turned to something subtle and sweet, as it is here.

Australia has a long history and heritage in video games, but very rarely do I see Australian game developers aim to contribute to our national body of narrative work like Wayward Strand does, and I cannot express in words just how admirable I find this effort to be.