Take Game Of Thrones. Take Princess Maker. Mash them together (after taking the sex out of both), turn the result into a spreadsheet simulation, and you’ve got Long Live The Queen. This ultra indie game is not without its delights and offers players a decent challenge on their way to guiding their princess to become the best queen the lands have ever known, but what lets it down is a decision system that’s as arbitrary as choose-your-own-adventure game books, and a low standard of presentation that redefines what it is to be humble.

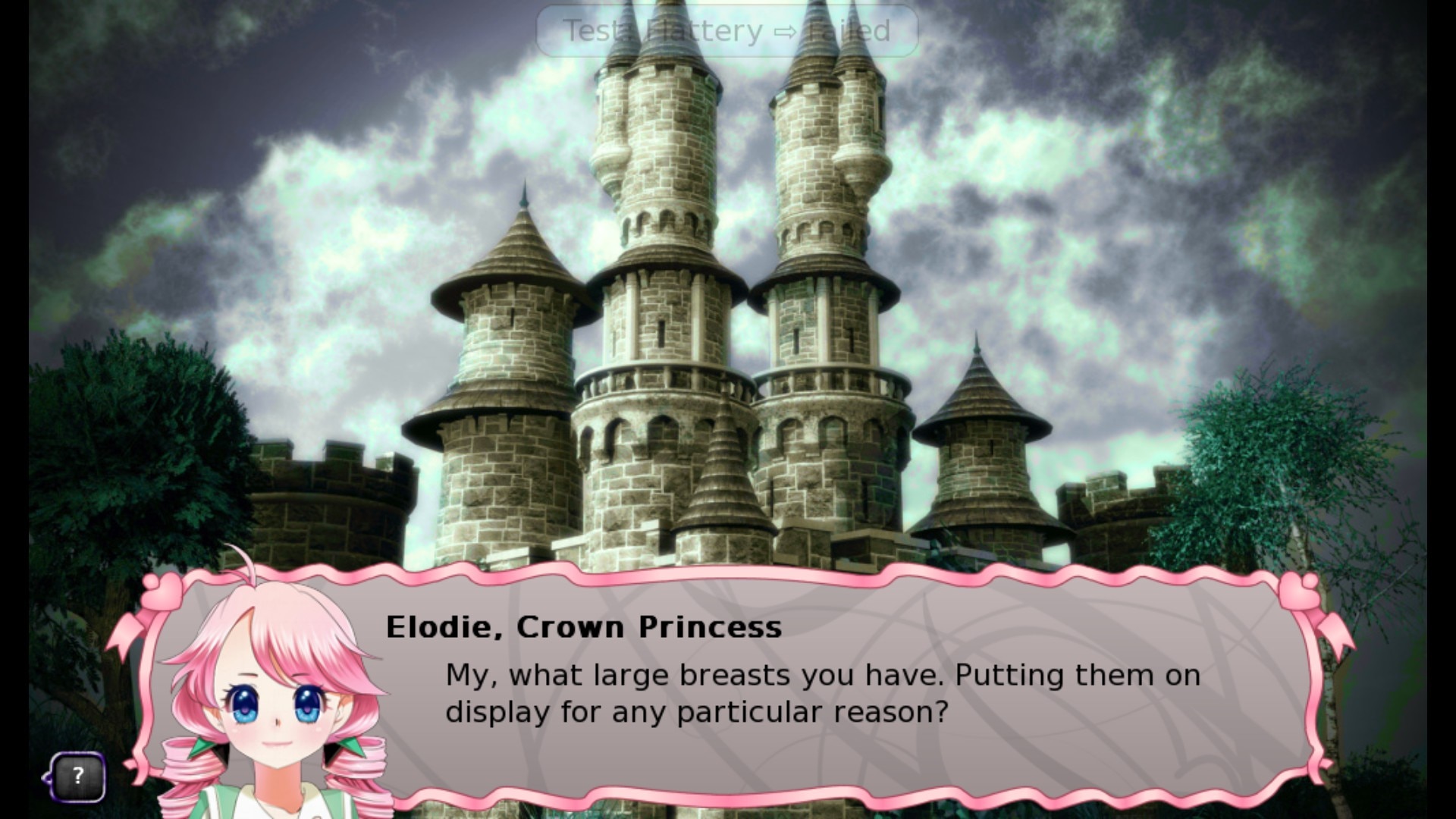

I’ll start with the former of those two criticisms, because whether you enjoy Long Live The Queen depends on your tolerance for this feature. If you’ve ever played a choose-your-own-adventure game book, you would know that the standard approach for these things is to give you a couple of different decisions at branching paths of the narrative, and for both of those decisions to seem like perfectly rational choices for the situation. Take one of them and you’ll be fine. Take the other and it’s death. A totally arbitrary death that you had no rational way of knowing was coming up. That was an unavoidable consequence of the simplistic and typically binary decision-making system (i.e. the limits of what a book could really do), and indeed became part of the charm of those things, but it’s far less excusable in Princess Maker.

There are plenty of ways that your character can die in Princess Maker. Many of them have to do with war or courtly intrigue (hence the Game of Thrones reference), and it’s very hard to pick which decisions will result in them. After one or two runs I realised that my best hope of ever training up a happy and healthy princess so that she can become a good queen (i.e. get the good ending) is to grab a notebook and actually jot down notes across multiple runs. It’s not too time-consuming to do so – no single run lasts more than a few hours – but repetition on the back of trial-and-error gameplay requires a very particular kind of patient soul to enjoy.

The payoff and reward is a surprisingly involved story. Princess Maker (at least, the one that I’ve played and is available on Switch) is nowhere near the storytelling experience that this one is. You play as a princess approaching her 15th birthday and the crown, and you’ll need to guide her through both the politics of the land and her personal development as she trains hard to prepare herself for that highest of responsibilities. This is a kingdom in turmoil. A group of lords will ask you to do something about an aggressive neighbouring nation that is invading. A local citizen will ask the crown for money to develop the printing press, and so on. The decisions that you make for these requests can have far-reaching consequences, and your princess’ ability to make good decisions is further complicated by her many statistics. If she has a high score in foreign affairs, for example, she’ll better understand the root causes of the conflict, and that’ll open up additional dialogue options (and usually good results).

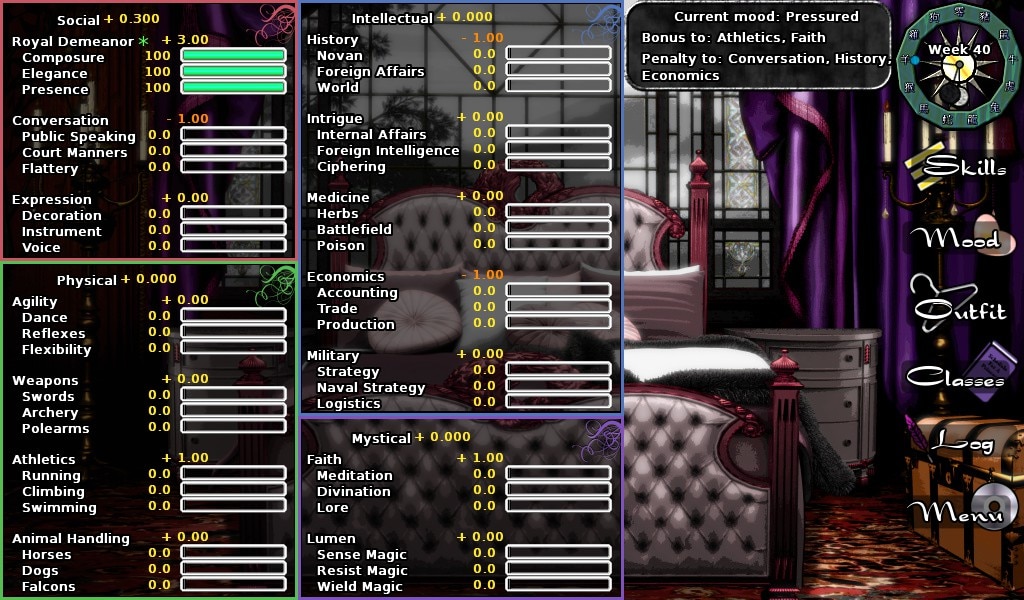

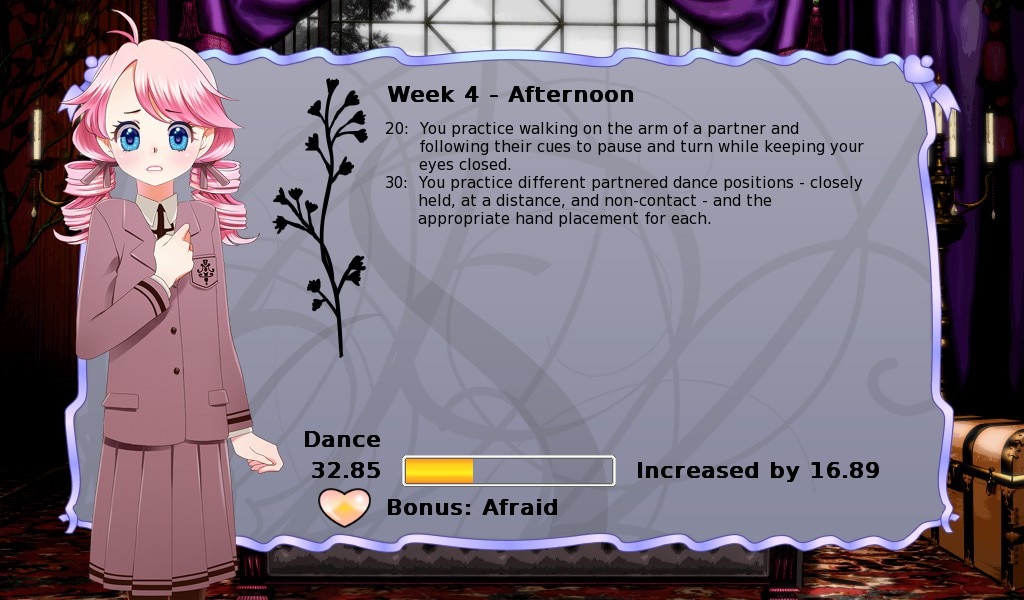

There are 42 different statistics that you can train your princess up in. Every single one of them will be questioned at some point through the narrative, and of course, it’s impossible to level all of these up to the max, given that you can only train in two per “turn” (week). You’ll need to decide early on what kind of princess you want her to be, and then focus her training her in those relevant stats.

Further complicating things are the princess’ moods. If she’s “lonely”, then some of the statistics will be difficult (if not impossible) to train in. Others will be boosted. If she’s angry, it’ll be a different set of stats that are neutered or strengthened. Once per week you can select from a group of activities that will influence four more statistics of the princess and those will adjust her mood.

If all this sounds like a lot, in an objective sense it is. These stats are important to passing skill checks that occur in the narrative along the way, and because there are so many stats, and after every “weekly” turn there are events that feature these skill checks, you’re going to be frequently failing them, especially if you’ve only played a couple of times and are not familiar with the ideal order that you’ll need to raise stats so you can pass as many of the important skill checks as possible (if not on this play through than the next one – hence the need for the notebook).

However, while there are a lot of stats to manage, the game itself not deep. There are no tradeoffs (so getting better in one stat does not result in a decline in another), and so the gameplay in Long Live The Queen really is just about choosing the right statistics to increase at the right time. It’s a very simple accumulation spreadsheet and that’s really all there is to the whole experience. After one or two play throughs it will remind you of office cubicle work. You’ll feel like Chandler from friends.

In fact, I’ve had the unfortunate experience of working with HR on projects in the past (don’t worry, not as an actual HR agent, but as a tech consultant), and the uncomfortable thing about Long Live The Queen is that it very much resembles the employee skill mapping software that HR professionals are so enamoured with. Other games (like Princess Maker) get away with very similar structures more because they feature animation and, generally, a personality, but the static screens and mundane presentation in this one draws it closer to prettied-up spreadsheet software. I’ve always felt that reducing people to a bunch of statistics and numbers is creepy stuff, and that impression became a barrier to overcome when playing this game, and even once I did I still felt it was all too dry for its own good.

That being said, as simple as its gameplay is, and as pedestrian as the presentation, Long Live The Queen has got a quality to it. The political environment that it depicts is interesting, and the way it weaves magic and fantasy elements into the kingdom gives the world an intriguing flavour. It just needed something to give it more energy, and some way to make it more than watching a bunch of numbers going up. Most of all, it needed to find a better way of handling endings than leaving you hoping that your princess does not find herself dead because she focused on studying poisons only for her to run into a situation where her lack of dancing skills causes her to trip, fall down a flight of stairs, and break her neck.

These are indie developers and they have captured the basics of the “princess maker” hyper-niche genre. They just needed to focus a little more on presentation and storytelling technique (unless your Yoko Taro, you’re probably not in a position to be writing in abrupt and bad endings without giving players some inkling that one might be coming up), and Long Live The Queen could have been something truly great.

I think there’s a legitimate argument to be made that Long Live the Queen isn’t as compelling as the Princess Maker games, but to say that LLTQ is an Excel simulator that reduces people to stats and imply that Princess Maker isn’t doesn’t bear scrutiny. Nor does the notion that a lack of flash is what hurts the game, because the PM games, especially today, are pretty humble affairs graphically speaking.

Personally, I think the real problem is that LLTQ focused on one portion of Princess Maker’s gameplay — the stats — while omitting the feature that humanized the game, namely the player’s parental relationship to the protagonist. The true point of the PM games was never to raise a girl to be a princess; it was to learn — in even a limited way– what it means to be a good father and to bear responsibility for someone’s well being and happiness. You could do that just as easily by raising your daughter to be a farmer or a writer, or what have you. LLTQ, as notably well-written as it is, lacks this humanizing relationship; the player is a disembodied spirit that attempts to play puppeteer for the protagonist, and that’s why, to me, it doesn’t match its predecessor. Picking isolated gameplay elements of PM’s design and dismissing the others necessarily diminishes the game; all the components are there for a reason.

I think we’re in fierce agreement here. Where you write “I think the real problem is that LLTQ focused on one portion of Princess Maker’s gameplay — the stats — while omitting the feature that humanized the game, namely the player’s parental relationship to the protagonist,” it’s pretty much what I’m getting at with the Excel comment. It felt dry and lacked the sense of humanity to me, just like reading an Excel spreadsheet. We have a different way of looking at it, but I think the slightly cold feeling the game left us with is similar.