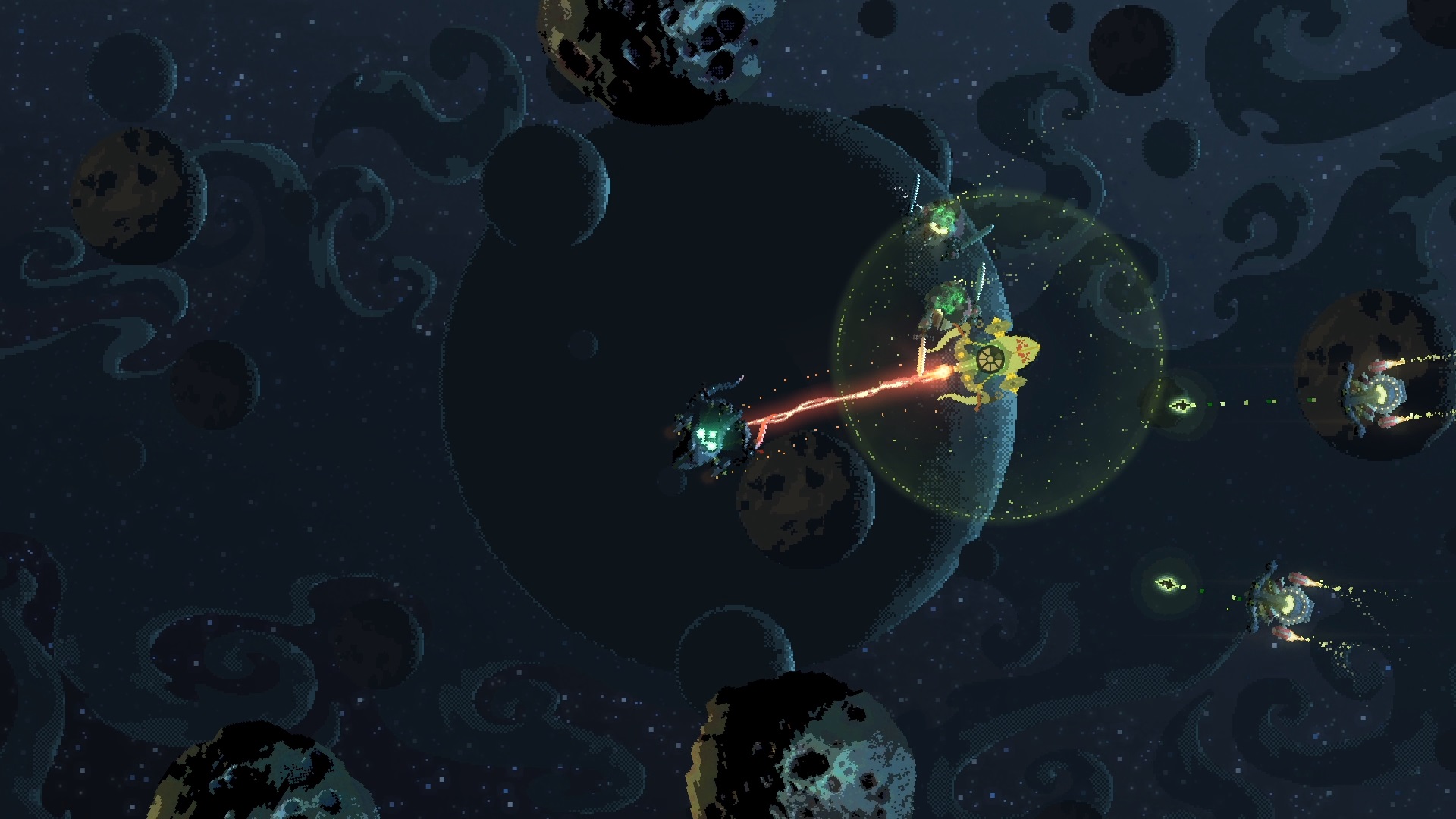

It’s not a combination that you would necessarily expect to see, but once you see it in action, it all makes sense. It’s eclectic, but very creative. Fabular: Once Upon A Spacetime combines science fiction spacecraft and battles… with the medieval in terms of the weapons you’re using. It’s the kind of game that only an indie developer could come up with, and we’re glad it exists.

The game is coming at some point this quarter, and in the leadup to its release we had the opportunity to sit down with one of the Spiritus team, Milan Batowski, about where the idea for the game came from, and what they’re trying to do with it.

Matt S: What was the appeal of moving from the big end of town to start up an indie development studio?

Milan B: It wasn’t that conscious of a decision. Back in the day, big development studios all went up in smoke in Hungary, so everyone started their own thing outside of gamedev. But we stayed close and did some hobby projects on the side. One of these projects was Fabular, and when it started to come together we felt it was something special and that we had to make it a reality.

That’s when we decided to go for it officially, and realised that it was something we’d all been wanting to do before: to work on something with full creative control and without having to make compromises due to rigid company policies and seemingly unreasonable publisher requests.

The curse of big companies is the huge financial risk involved in innovation which they are seldom willing to take. We’ve all been innovators in our respective fields of work. Always wanted to broaden the horizons of what players can expect, but do so in a way that feels familiar and yet takes them to a place where they’ve never been before. We think we’ve struck this balance with Fabular and feel that it’s a worthwhile project to risk our own livelihoods on, because it has the potential to add value to the gaming scene.

Matt S: The art style for this game is very distinctive. Where did it come from and where did you draw inspiration from?

Milan B: Indie gamedev, in the traditional sense, is similar to ‘cooking with ingredients that you happen to have in the fridge at the moment’. When we opened our fridge, we found an Art Director there who’s a classically trained pen and paper artist, with a knack for building worlds and a crush on chivalric culture.

It’s not an everyday setup for a very small indie team to have an Art Director, but we had to cook with the ‘ingredients we had’. We’ve already had a programmer and a designer + graphic artist + all rounder, so we began to shape the game around the skill sets of the three of us.

That is why, in our case, visuals are very prominent. Most small indie projects don’t have the luxury of someone to direct their visuals, so they have to neglect that area and try to compensate with outstanding gameplay. In our case, visuals are one of the three pillars of the project, besides code and gameplay.

In terms of inspiration, it mostly came from our innate needs to pair seemingly contrasting things together. Such as archaic vs. modern, small vs. large or charming vs. frightening. If we can depict these antagonistic notions in an environment that is consistent in its set of rules, they provide the perfect amount of tension to keep the viewers entertained, while giving them something fresh to experience.

Our basic idea that ignited everything was that we wanted to make a medieval folktale in outer space. We’ve slowly built a world around that idea, with its own characteristics. And later, when we’ve added new things to the world, they all had to adhere to those characteristics to be believable.

In terms of the in-game pixel art, it’s partly a skill-set constraint as we don’t have 3D modellers on the team, and partly a childhood fantasy coming to life. Having 2D pixel art objects respond to real-time lighting is something we’ve all fantasised about growing up in the 90s. And it still amazes us when we look at our battlefield objects.

Matt S: It’s safe to say that roguelikes are a well-trodden space these days… to the point where people are starting to get tired of them. How will your game distinguish itself, in terms of how it plays, to the rest of the roguelike genre?

Milan B: The basic structure of the game is supposed to keep things varied with the constant rotation of the battle, encounter and management parts. Of course the meat of the game is the action phase, but after you get your adrenaline rush, you usually have an event where you can delve deeper into the universe, get to know locations and characters, and handle situations with multiple outcomes. Then you have the management part, where you try to find the most optimal route through the given realm on the star map, manage your resources, trade and upgrade your ship, and try to find the best build for your playstyle.

The battles themselves are not the traditional roguelike twitch shooter kind either. Our combat is much more tactical and slower paced – maybe more akin to a Souls-like game than a Roguelike. Controls are based on a physics system with momentum and inertia, which makes our battles very different from most games out there. It takes a bit of getting used to, but has a lot of depth to it if you want to master it. Not to mention you play as a spaceship that has swords!

Matt : Why are indie developers so attracted to roguelikes as a development foundation?

Milan B: It’s probably mainly that randomisation and procedural generation allows us to create emergent gameplay that is not pre-scripted and does not require a lot of content to be made. Indie teams are small and making audiovisual content takes a lot of time, so this is probably the only way for a small team to create something feasible in a given time is to use procedural generation.

Another reason might be a nostalgia factor. Most indie developers are more experienced devs that split from bigger studios, who grew up in the 1980s and 90s, when games were hard and punishing by nature. Most of the time you had to restart from the beginning after you died. This is replicated in the roguelike genre, and it elevates the game to another level as stakes are higher, failing hurts more, but success is even sweeter.

As a developer there is also the allure of making a game that can even surprise its own developer by not being pre-scripted, but procedural in nature.

Matt S: What are you hoping players will take away from this game?

Milan B: Fabular is an idealist game in its nature. It supports ethical decisions – there is no way to role-play as evil in the game. You get ahead in encounters if you choose the morally good option, which for us is an important message, and we hope it’s something that players take away from the game.

Although you can, and must engage in combat, the game does not put battles or destruction in the limelight, but rather emphasises humour, the charm of fairytales and sunny idealism.

Matt S: Is Fabular a one-off, or are we going to see more work in this world going forward?

Milan B: Fabular’s universe has been developed very thoroughly over the years, alongside working on the game itself. It is developed enough so that products in other mediums may spring out from it such as a novel, comic book or even a tabletop RPG. This universe is very dear to our hearts, and we would very much like to work on it in the future as well

Matt S: One thing I did notice about the game is that the movement looks like there’s a bit of inertia involved. Coupled with the melee focus, I could see this taking some work to master. What have you done to help make this game more accessible to a broader audience, or has this always been a “hardcore” game?

Milan B: I wouldn’t say Fabular is hardcore – it’s just novel. Having a combat system based on physics is a unique characteristic of the game, and each new thing in life takes some getting used to, because you have nothing to compare it to, so you have to figure out things on your own.

And when you do figure things out, it has the potential to entertain you much longer and provide much deeper gameplay than a traditional shooter or brawler.

Also having momentum and inertia supports the idea of depicting chivalric duels in outer space; to feel the weight of armour and the clash of steel against steel.

Matt S: Finally, what does success look like for you, both for Fabular and your studio in general?

Milan B: This game is being made with a lot of care and perfectionism. We pour our hearts and souls into it because we believe that it can provide a new inspiration into the genre and bring joy to all players, but particularly to those who are striving for something fresh and unique.

If we can achieve that, it will be a success for us as developers. If we manage to combine that with a number of sales that allows us to continue working on it, and potentially on other products in the future, that would be a success for our studio.