Hundred Days is one of those wish fulfilment simulators that I am so glad exists. I love vineyards. I love touring them, tasting their boutique wines, and then staying for an à la carte meal at the vineyard’s inevitably pretentious-but-tasty restaurant. The food is always perfectly matched to the wine, naturally. And then I love getting my camera out, because I love the neat rows of vines and the photogenic aesthetics of the space. Vineyard visits are an all-around and genuine cultural experience, in other words, and I have always wanted to run a vineyard of my own.

Hundred Days reminds me that I’d be very bad at it, if I ever somehow end up with enough money to purchase a farm (buy my Dee Dee Zines, friends!). Winemaking is undoubtedly an art form, relying on a near-spiritual understanding of grapes and a vision for what they can be turned into. That side of things I do think I could develop. It’s just that winemaking is also a STEM-based art form that is very much science first, product second, and I just don’t have the discipline for that. Hundred Days is presented elegantly and even minimalistically, but it does cover just about every process involved in the winemaking process, and it’s a tough thing to manage. Especially when the commercials start to get involved too (but more on that soon).

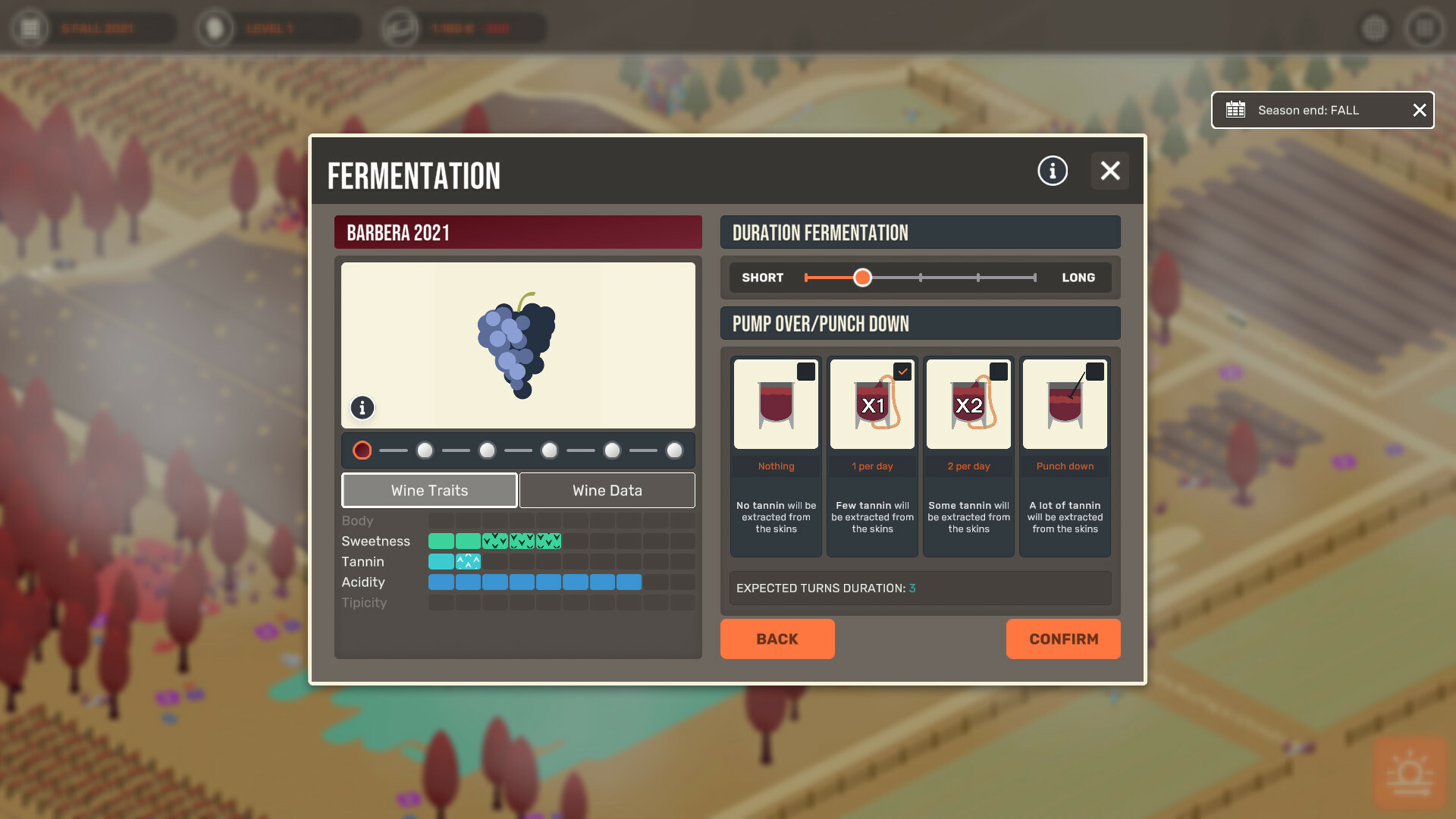

You’ll learn how to play the game in about an hour. Basically, you’ve got a small grid of squares in the middle of a single screen. That grid is an abstraction that represents all your farmland, and it can be expanded via “technology” upgrades. Then, with each season, you’re dealt cards that represent the various stages in the winemaking process, from tending the soil to bottling the completed product. Once you play a card to the board, you’re given a Tetris-style block that you need to fit to the grid somehow, and, I know this will be a complete surprise to you to hear, but you don’t always have enough room for all the activities. Strategy!

This system is as abstract as it probably sounds to you, but as difficult as it might be to conceptualise, in action it is clean and efficient, and once you get over the initial confusion that comes with high levels of abstraction (what do you mean I have four different plots of land, but just the one board to manage them all on?), Hundred Days is a highly playable and interesting spin on the simulation genre. As minimalist as its mechanics are, though, the actual management is anything but straightforward. From dealing with acidity in the soil, to balancing out the tannins, sweetness, body and quantity of wines bottled per vintage, you do need to run through just about every aspect of actual oenology. Then, once you do that you’ll need to worry about selling the wine, and that means making a high enough quality drop that people want to buy, in large enough quantities to fuel your ever-growing need for employees, land, and technology.

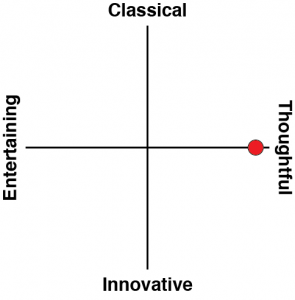

The heart of Hundred Days is far sharper than its warm, almost nostalgic aesthetic would suggest. It actually feels like Hundred Days is really very angry at the way that big business rips the soul out of winemaking (hello, Australia’s Yellow Tail!). You’ll start out with the best intentions, running tiny runs of the highest quality wine that you can, and perhaps even experimenting with different approaches to winemaking, risking a lower rating but balancing that out against the potential of producing something special. But then you’ll realise that the only way for your farm to survive, for the land to continue producing wine, and for the business to stay open is to continue growing, taking on additional expenses, and slowly ramping up production. You’ll go from selling one or two bottles to collectors that have dropped into your vineyard to try a local and unique drop to focusing exclusively on the retailers and distributors who don’t even have a face, but certainly buy in large enough quantities to make interacting with them worth your time.

The game never explicitly goes out there to state “business ruins everything” (though there is one character in the story mode that represents the Bezos-like figure and he is a pain). It’s far too smart for that. Hundred Days is much more organic in its messaging. You’ll realise that this game is effectively anti-capitalist because, while you’ll delight at first in carefully designing labels and picking premium bottles and corks that up the cost but make you prouder of that year’s vintage, by the end game you’re cynically throwing tepid but scientifically-optimised grape juice into any old bottle and using the cheapest cork because you’re making better margins when selling in volume that way. That’s the point that you’ll stop caring to play… so you’ll start a new game instead, because you’ll realise that you’re having more fun when you can focus on those tiny runs of wines that only the locals will ever know about.

It’s an odd inversion of simulators. In most cases, simulators get more interesting and entertaining the deeper you get into them. Sim City is so much more interesting when you’re managing a metropolis of a million than a village of 100. Planet Coaster is a joy when you’re rivalling Disneyland more than it is when you feel like you’re running a school fair. Thanks to the abstract, puzzle-like design and minimalistic aesthetics, Hundred Days goes from being a simulation where you feel like you’re joining the developer in celebrating the wine-making process to being something that, simply, feels like work and production. I mean this in a good way, as it is a bold and compelling message that the developer has shared here. It’s just surprising that anyone would front-end the positive experience in a simulator like this.

Warmth infuses everything about Hundred Days. The narrative mode is compelling, thanks to an eclectic cast of characters and that gorgeous art style. For a game that’s so menu-driven, the interface is clear and readable and the information that you need to make decisions is easily accessible. And, while I did find myself in my role of winemaker becoming ever more cynical about what I was doing and the business that I was running, there was still some neat emergent storytelling that speaks to the game’s nostalgic tones. For example, even though you can sell a complete vintage out, I always made sure I kept six bottles of each year’s production. Why? I’m genuinely not sure. It’s not like I could actually drink them. However, if I ever do own a real vineyard, that’s exactly what I would do; save six bottles per year for myself. So perhaps, even as I found myself turning into Bill Gates The Wine Content Producer in Hundred Days… perhaps that underlying longing to own such a unique and artistic business as a vineyard never quite left me.

Hundred Days is a fascinating little experience. I didn’t expect it to be a graceful little anti-capitalist dig, but I rather love that it is. It didn’t discourage me from wanting my own vineyard one day… but it certainly reminded me that I never want anything I do to become so big that I stop caring about it, and it’s a rare quality for a simulator – or any game – to subvert the expected experience to deliver a powerful message like that.