On the one hand, there’s a lot to admire about Ghostwire: Tokyo. There’s a clever concept in there, and the Noh theatre influences seem to run more deeply than just the masks that you see on the antagonists and the game’s key art. It goes without saying at this point but I’m also quite enamoured with the aesthetics, storytelling and spirituality of Shinto, which is a powerful influence that runs core to this game. Whenever Ghostwire: Tokyo is not behaving like a video game, it’s quite remarkable.

Unfortunately, whether it was the influence of Bethesda or one of the creative leads within the developer, Tango Gameworks, on the game side of Ghostwire: Tokyo, it’s a different matter. At some point, people decided that a mixture of generic open-world mechanics and structures and cumbersome first-person combat would be sufficient. There’s a severe disconnect between the game’s concept and its moment to moment play, and that very nearly ruins it.

But to start with the good. Shibuya, where the bulk of Ghostwire Tokyo takes place, is one of the most vibrant, energetic, and exciting places on Earth. The city itself is a consumer’s playground, and while just about everyone knows the fascinating experience of the Shibuya Scramble – the busiest road crossing in the world (and these days a push-and-shove to get past all the tourists that decide that they must have a photo from the middle of the crossing during the 30 seconds that the lights are green) – the entire area is a colourful, noisy, sensory experience. From cafés to pubs, a Disney store to a 10-story music goldmine, alternative fashion to kawaii and business attire, Shibuya is the millennial’s ultimate shopping Mecca.

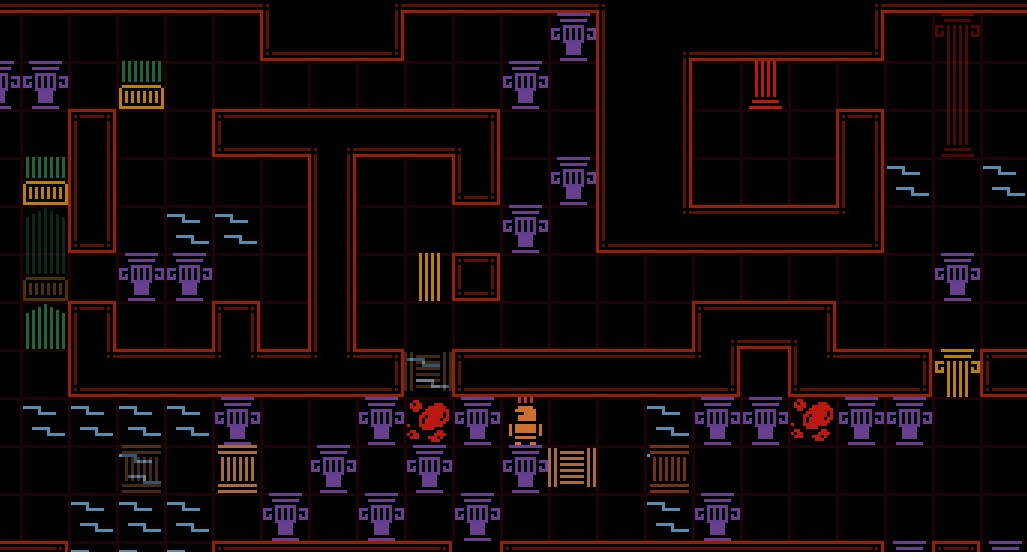

Now consider removing all the people. Leave the noise and bright lights, but take away the movement of bodies that is so iconic to the area. It’s an eerie thought, right? That’s the atmosphere of Ghostwire: Tokyo. It’s a deeply surreal and eerie place, doused in perpetual fog, the glow of the combination of a red moon and neon, and frequent downpours, where you’ll feel isolated and alone in the place where you would least expect that to happen.

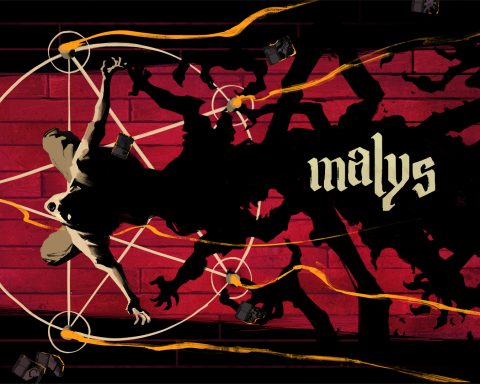

Then there are the Noh theatre elements. The first clue that the game has something to do with that is the masks that the bad guys wear. The main antagonist is wearing a variation of a Hannya mask (representing a female oni), and not only does that give him a sense of malevolent mystery, but it is an iconic feature to Noh, so much so that anyone who is familiar with the theatre form will start looking for Noh elements in the rest of the game. The music then backs that up. It’s not true Noh music and closer to the kind of music you’d expect to hear at a traditional ceremony, but it shares an eerie stillness to it (aside from the deliberate moments to break from that for dramatic effect or to re-assert the modern side of Shibuya), that complements the empty aesthetic and reinforces the sense that there’s going to be some serious yūgen going on in this game (for more on yūgen, which is beyond the scope of this review, read the feature I wrote on Noh theatre in this month’s Dee Dee Zine).

Interestingly, given that Noh is generally associated with Buddhist thought, much of what you do in Ghostwire: Tokyo is more Shinto in orientation. But that oddity aside, it’s also elevated and theatrical, and makes a good point of blending tradition and modernity in a way that is so emblematic to modern Japanese spirituality. You’ll be running into yokai, liberating shrines (for the uninitiated – Torii gates are features of Shinto shines, not Buddhist temples), and collecting artefacts drawn directly from Shinto religion and aesthetics. Set against the neon colours and towering skyscrapers of Shibuya, this blend of a Buddhist theatre style, Shinto aesthetics and modern neon-noir Japan is gorgeous, and Ghostwire: Tokyo is a rare AAA-blockbuster treat in that regard. It certainly made me homesick for a country I’ve been locked out of for more than two years now.

Adding yet another layer to the game’s gorgeous blend of themes is the dry and typically Japanese sense of humour that runs through Ghostwire: Tokyo and underneath its many more dark and horrific elements. Unfortunately, as delightful as those are, I’m not sure will fully translate to the west, as they often speak to parts of Japanese culture that is only really known to the Japanese. Nonetheless, the presence of that humour is a unique quirk that distinguishes it from the open-world games of the west. For a very simple, tiny, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it example: there’s a scene very early on where you need to go and liberate a public bath from malignant spirits. Once you do so, as you exit, you’ll be able to pick up small bottles of coffee milk. It’s something that your protagonist tells you he has been craving from the moment he stepped into the bathhouse. It’s the kind of dialogue and “reward” that will seem odd to players… except those that are familiar enough with Japan to know that a small bottle of milk is absolutely something you’ll look forward to after a visit to a sento bathhouse. Then that random bit of dialogue, and break from the seriousness of the quest, will make you chuckle more than a little.

As I got into the rhythm of the game I found myself frequently checking out the side-missions for the opportunity to run into tanuki, kappa, and other wonderful things from Japanese legend that had suddenly found themselves all concentrated into Shibuya. I don’t usually pay active attention to what I’m doing in open-world games, since I find chasing the stream of busywork icons to be exhausting almost as soon as I start playing, but the additional context and texture that could only come from Japanese developers making a game about their own culture helped draw me in far more than usual this time.

What lets Ghostwire: Tokyo down is that it has all this distinctive, interesting, and culturally Japanese stuff going on, and then shoves it into the kind of content-driven best practices that we expect from every other modern Ubisoft and Sony game. With Ghostwire: Tokyo, I didn’t want to “liberate” shrines in the same way that I captured bases in Horizon or Far Cry, and I certainly didn’t want the same rewards for doing so. When I was in a battle with a creepy blend of Slender Man and Japanese salaryman, or taking on a horde of headless ghost schoolgirls, I wanted the fights to play out in a different way to the usual horde of bullet-soaking zombies or rebel thugs. When I ran into a creepy child-ghost in a raincoat (a great reference to a popular Japanese yokai story!), I so badly wanted it to be a bit more of an encounter than a standard monster that summons more monsters… a template of what we’ve seen in dozens of open-world efforts in the past. Finally – and this one really irritated me for some reason – when I was exploring the city and came across a tengu, I wanted a memorable and meaningful encounter with a tengu. Not a zip line for reaching the roof of a building like the creature was a grappling hook highlight spot in a Tomb Raider thing.

Basically, the gameplay should match the theme. Unfortunately, with Ghostwire: Tokyo, there’s an incredibly strong theme that has been stuck on top of Generic Open World Experience #197651, and that disconnect is frustrating. Nothing about this game played like it looked like it should, and despite being as big and lengthy as an open-world game usually is, I was never able to make the connection between what the developers did with it, and the story that they were telling. It very much feels like there were two different teams working on this game in parallel. Two teams that somehow forgot to talk to one another.

Ghostwire: Tokyo goes through all the necessary motions. The investigation mechanics are fun. The side quests are all little story-driven vignettes in a way that has been the best practice since The Witcher 3. The combat is certainly challenging enough on the higher difficulty settings (and will require you to use stealth at times), and there are multiple skill trees to level up, complete with the need to find rare items to unlock the higher tiers of those skills. There is an endless stream of collectibles and points of interest to keep you scoring every corner of the world… and yes, you can pet the dog.

It’s all there, in other words. Furthermore, there’s nothing technically wrong with any of this and it could have been dropped into a Ubisoft open-world game and no one would bat an eyelid at it (assuming that you replace the use of magic with more conventional weapons, naturally). But that’s also precisely the issue I have with the game. Ghostwire: Tokyo, for something that is so distinctive visually and thematically, is in desperate need of its own identity in how it plays. Say what you will about Kojima’s Death Stranding, Suda’s No More Heroes, and Suehiro’s Deadly Premonition, but while these kinds of open-world experiences might be far from perfect, in each case the world and gameplay existed to support the concept in theme in a way that made them complete and distinctive. That is a quality that Ghostwire: Tokyo sorely lacks.

You’re going to have fun with this game. For the criticisms I list above, I do think that Tango Gameworks has, with guidance from Bethesda (no doubt), created a refined and highly playable open-world game. It’s one that ticks all the boxes and does so in such a way that’s hard to actively fault. Yet, it’s also so frustrating. The hints of what the developers wanted it to be are there. They wanted to make a Noh-inspired, yurei-and-yokai drenched blend of Shinto, Buddhism and neon-modern Japan. That would have been incredible. Sadly that didn’t happen. Instead, I was left with the impression that I’d just played a Ubisoft Goes To Tokyo farce, and that left me feeling very deflated indeed.