I’ve been fortunate in that I was able to go into Doki Doki Literature Club Plus having never played the original, and also not knowing a whole lot about it. I was aware that it was a horror game and the initially bright and bubbly presentation was all a ruse. I knew that it was a game that looked and felt like a dating simulator, right up until the point that it veers in a wildly different direction. But that’s all I knew about it, and therefore Doki Doki Plus was able to land its full impact on me.

It really is a clever game. A lot gets said about how western visual novel developers often play with the anime VN format with less-than-genuine intent to satirise or criticise the form, and Doki Doki Literature Club is probably one of the earlier examples of that. With that being said, where a lot of other western VNs do so purely for the purposes of mockery – subversion-as-insult, as such – there’s some genuine and – I believe – well-meaning deconstruction work at play with Doki Doki. It aims to pull at the very structural threads that bind the “dating game” visual novel together to better understand and appreciate it.

I know that what I’ve written there is vague, but it’s difficult to describe how Doki Doki does its deconstruction without giving its messaging away, and I’m going to assume that there are some people out there who, like me, have the opportunity to experience the game for the first time here. What I can say is that Doki Doki uses every trick at its disposal; it makes heavy use of fourth-wall-breaking interactions directly with the player (rather than the avatar that represents the player). It plays with pacing, too – the subversion starts to happen so late into the game that, right before it did, I was actually wondering if the reputation that the game has was itself some kind of meta-joke across the Internet. It plays with the idea that the few choices that you make in dating VNs matter. It leans into the same kind of self-aware storytelling that makes creepypasta stories so fun, and ultimately, Doki Doki’s satire remains fun throughout in the same vein. Even in its darkest moments (and it gets so incredibly dark) there’s a wit about the game that remains overwhelmingly entertaining.

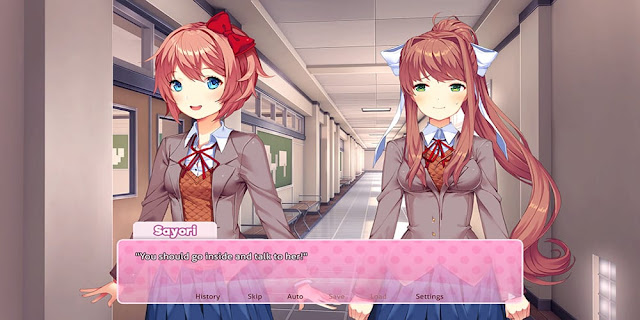

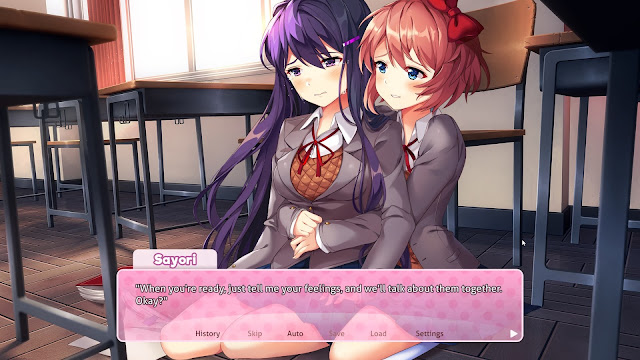

Right from the start, the game gives you plenty of content warnings, and you should heed them. Without giving anything away, if you’re sensitive to particularly uncomfortable themes and visual imagery, then you really should heed the content warnings. It’s a good thing that the game has these content warnings, of course, but they do undermine the impact a little bit, in that, even if you don’t know the story, you’re effectively being told to expect to be shocked. Still, the game’s art doesn’t hold anything back, and while you could probably argue that there’s not quite enough done in the setup to make these characters truly engaging before the horrible things start happening to them (they’re caricatures of dating game girls – deliberately so as part of the game’s broader themes, but it’s still shallow characterisation as a result), the art is explicit enough to still elicit a response.

Indeed, for a game that was originally launched as a freeware hyper-indie project on itch.io, the production values are particularly impressive. Doki Doki Literature Club has limited scope – most of the action happens in one room, and there are only four characters to interact with – but those characters are drawn beautifully, have a wide range of different emotions, and the use of CGs is on-point to deliver key scenes to players. The poetry mini-game that’s part of the experience is a lot of fun to play around with (even if it’s ultimately only there in service of the subversion), and the bright, happy music is composed perfectly to also start to suit the creepy, creepy vibes that the game develops.

For all I’ve written above, Doki Doki Literature Club really isn’t really interested in being a game. It’s more a kind of interactive essay, which isn’t about presentation values, beyond their ability to enhance the bait-and-switch that sits at the heart of the subversion. The four girls in the game represent various tropes that are common enough to dating games, and the narrative itself works hard to give you the impression that you can “win” with one of them, effectively possessing them as is standard for the genre. This is something that Doki Doki’s developer clearly struggles with, and wrests that agency over which girl you get to “own” away from you, as a way of representing the unhealthy approach to romance that typifies this genre. It’s not judgemental about it, and the game’s rhetoric is not there to shame anyone that plays Doki Doki and then goes on to enjoy traditional dating games again, but it was important that these girls all looked like traditional dating game characters for that discussion that the developer wants to encourage to properly come across.

In the end, Doki Doki Literature Club (and this Plus version) is both a homage and a challenge. It’s a homage in the way it delightfully plays with the dating visual novel genre – sure, it ends up subverting that to horrific effect, but there’s such glee in how it does that that hugely entertaining. On the other hand, it’s also a challenge – a suggestion that the genre can be a bit more reflective, look for ways to approach things differently, and that there is a lot that this genre can do with characterisation and relationship dynamics. The director has been outspoken that the initial seed of Doki Doki Literature Club from his “love/hate” relationship with anime and VNs. There’s much more of the love in there, I think, but developers making games in this genre should certainly play this game to encourage them to think about the structure of their own work from a different angle.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @mattsainsb