It would be so easy to look at Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne, view its unrelenting darkness, its crushing, claustrophobic difficulty, and the heavy use of religious aesthetics and iconography, and just assume that all of that is in the service of a kind of primitive nihilism, and a laboured reading of Nietzsche’s “God is dead” catchphrase. Now it’s certainly true that SMT III is relentless, claustrophobic, and dark. My read is that it is so much more than a reduced understanding of nihilism, though. Rather, this thing is a true example of transgression. It’s not transgressive because it will offend, though. We’re talking real transgression here; Nocturne will challenge. And it’ll challenge not just your JRPG button-pressing skills. This game’s designed to make you challenge your perceptions on everything.

“The fact [is] that these two complete contrasts were identical – divine ecstasy and extreme horror,” Georges Bataille once wrote. I believe that Shin Megami Tensei is much closer to a depiction of that particular idea bubble than the Nietzsche “God is dead,” quip. At the start of SMT III, your character goes through a rapture, as the world meets its end. Rapture, of course, has a dual meaning – it is a word meant to symbolise a violent end of things, but it’s also something ascendant – an ecstatic lifting of the soul to paradise. Our hero, in SMT III, doesn’t get to ascend to paradise. Instead, his body is torn, and replaced by something melded with demonic power. He wakes to find the world transformed into a hellscape playground for ravenous demons and worse. From there, he embarks on a journey for meaning. His “paradise”, as such, comes from the discovery of that meaning to it all, and his eventual chance to shape it all in his image – to, effectively, become God.

What he goes through is almost a dictionary-definition limit-experience, to use a term associated with Bataille and later philosophers like Michel Foucault. He reaches “the point of life which lies as close as possible to the impossibility of living, which lies at the limit of the extreme,” as Foucault described. Frequently, through the course of SMT III, characters are quick to remind you that the world has ended. It has raptured, and you have only survived by being transformed into something only half-human; you’ve transgressed the limits of humanity. Your character has hit the point where life lies as close as possible to the impossibility of living, and mechanically SMT III is brutally unforgiving as a game to play precisely so it can reinforce that notion; that exquisite agony of sheer frustration as a boss beats you down over, and over, and over again is there to reinforce that extreme experience of being somewhere right at the edge of the ability to “live” in this world. I’m glad that there is an easier difficulty option in the Remaster for people less invested in the game’s purity as philosophy, but the lower difficulty level certainly undermines the powerful depiction of this game’s dark majesty.

To Foucault and Bataille, the limit-experience was the opportunity to arrive at a new understanding of the thing that you transgress. A new understanding, now unburdened by constraints imposed by the limit. To transgress is to break the boundaries – the limits – of existing knowledge, and to cast an eye back at existing knowledge and examine it from a new lens. Unsurprisingly, then, your quest in SMT III is focused on some deeply human concepts, which the developers have termed “Reasons”. I can’t get too detailed here because of spoilers, but your goal, throughout the game, is to obtain enough power to shape a rebirthed world in the image that your protagonist has decided is the right Reason, subsequent to the limit-experience that they have gone through. The heavy implication here is that the rebirthed world is a somehow superior – even ultimate – expression of humanity because it has been shaped by the limit-experience of having transgressed the human.

Now, this is my reading of Shin Megami Tensei. It’s certainly not the only valid one, and indeed you can form a nuanced Nietzschean reading on it if you wish: “The game goes from hard to frustrating within the first 15 hours of gameplay, and as players progress through the 70-hour game, many continually ask themselves if all of the effort is actually worth it,” writes a fellow called Sam Hatting in his own, excellent, reading of the game (one that avoids trying to narrow Nietzsche to “God is dead” nonsense). “This is because the game’s difficulty and underlying themes are representative of Nietzsche’s Übermensch theory introduced in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in which man must be driven to overcome all obstacles in order to ascend to the status of Übermensch, or Overman.”

Note the common point between our readings; they’re both concerned with the way the game focuses on a search for meaning and reason. In a similar vein, it would also be quite silly to deny the theological reading of the game. SMT III borrows its religious iconography from everything from Christianity to Hinduism and on to Zoroastrianism for a reason, and theology, as we all know, is itself very much orientated towards the search for meaning. I, a student of transgression, have my reading, but the crux of SMT III is this: if you let it, this game will run you a full thesis on meaning – the meaning of life, reality, thought and experience – and do so from a multitude of different perspectives and arguments. That’s why I love this game so much. Beyond anything else, it’s just smart. Even if you’re not going to sit there and write an essay about it, its underlying intelligence is explicitly there with every moment that you play.

It really is no exaggeration that the game is brutally challenging, to the point of cruelty, though, and that’s going to put more than a few people off. Going back to play it in the year 2021 has made a few things particularly clear; firstly, it’s not just that it’s difficult. It’s that the difficulty is unrelenting. There are almost no areas across the entire game – including those where you do your equipment shopping and chat to NPCs – where you’re not seconds away from a random encounter. Monsters will jump you two steps from any of the rare save spots, and if they really get the jump on you, then tough luck, but you’re going to have to reload, and the last save you actually managed to get in might be an hour back (or more).

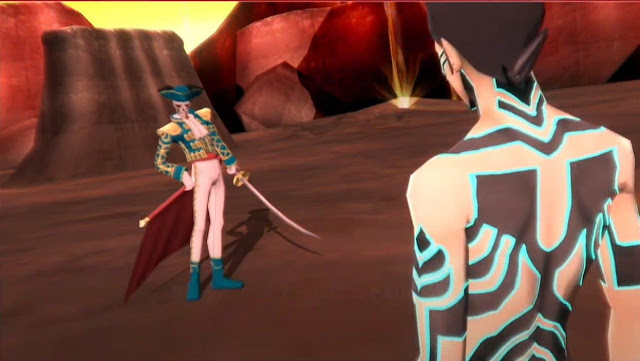

Bosses, meanwhile, are just ridiculous. My favourite boss of all time in JRPGs actually comes from SMT III, and he’s my favourite – I suspect – because I’ve been Stockholm Syndromed into loving him. He’s a skeleton matador (who looks awesome in HD, mind you – see above), and you’ll be running into this little delight very early on in the game, when you’ve still got a relatively limited pool of abilities and powers to bring to bear against him.

So, to quickly explain this combat system and why it makes this fellow such a pain: in SMT III, you’ve got a team of characters, and on your turn, they all get a single attack initially. If you hit the enemy with something they’re weak to, you get extra attacks. If you hit them with something they’re resistant to, or miss them entirely, you lose attacks. Our buddy Dreamy Skeleton Matador boss, in his first turn, massively ups his evasion rate (meaning you’re going to miss him a lot), and then utterly pummels your party with group elemental attacks that are common enough. One character in your party is almost certain to be weak to it, giving him extra attacks on his turn. Add to the fact that on a very pure basis this guy hits harder than your party’s healing capabilities are likely to keep up with and… well, ol’ Skele cost me a lot of restarts when I first played SMT, and a fair few this time around too. Finally, as the real clincher here, he is, effectively, the first boss you’re actually going to fight.

You would think that a game that is effectively Dark Pokemon would make it easy to game this “strength/weakness advantage” system. You’ll assume that you can just stack your party with the right set of monsters, and cakewalk it through anything. Just like Pokemon. It is easy enough to recruit a large roster of fallen angels wearing fetish gear and even more kinky-costumed demons (you just talk to them during a battle, and if you give the right answers from binary choices, they join the squad). Yet somehow this combat system is so open in scope, and the developers had such an understanding of it, that over and over again SMT III brutalises you, no matter how well you think you’re playing. It’s majestic. It’s… rapturous… and it’s the reason I’ll only ever play this game on its pure difficulty setting. The combat’s brutality is very much part of the overall game’s aesthetic and tone.

Now, as far as the Remaster goes, there is that lower difficulty setting for people that just want to get to those endings, and as I mentioned earlier, I think that’s a valuable thing to have here, else a too-large percentage of players will simply never bother. The visual touch-up job has been relatively minimal, but it’s nice seeing the kink wear of the female demons in sharper detail, and the overall art design of SMT III was always impeccable, with the shift to HD leaving that untouched. It only runs at 30fps, which seems to bother some people based on the response to previews, but on account of the game being a turn-based thing, I had better things to focus on as I played. In fact, if anything, the relatively minimal “modernisation” of this experience plays to its strengths, reinforcing the grungy underground and transgressive spirit of it. It’s like how some of the more raw rock bands do sound better on vinyl; a particularly appropriate statement to make here because this game has a “low-fi” hard rock soundtrack that would absolutely sound better on vinyl.

Shin Megami Tensei III: Nocturne was one of the first games I ever reviewed as a game critic, back on the PlayStation 2. I was mesmerised by it then, because I found it to be a deeply challenging, but also deeply rewarding JRPG, and its dark, genuinely adult theme wasn’t so common for JRPGs back then. 18-odd years later, my interest in games has shifted slightly, and I’d like to think my capabilities and depth as a critic has matured. However, this game continues to compel me. It is thought-provoking, deeply creative, and a genuinely serious JRPG. Oddly enough, one of the qualities that drew me to the original has drawn me back to the remaster: we still don’t get so many of those.

– Matt S.