Note: This is a review of both Famicom Detective Club titles released together: The Missing Heir and The Girl Who Stands Behind. Though they have different narratives, they are functionally and mechanically the same, and since this will be a spoiler-free review that won’t talk about the narratives at any level, I didn’t see any reason to review them separately.

I am very grateful for whatever possessed Nintendo to localise the remakes of Famicom Detective Club duo, decades after the originals landed on the NES. For so long now this has been one of those “hidden gems” within Nintendo’s deep and wide library of titles. We’ve never been able to play them out this way, but they’ve always been well-regarded back in their homeland. I understand that respect now. These games are magnificent, and Nintendo partnering with a visual novel specialist, Mages, to modernise them was an inspired choice.

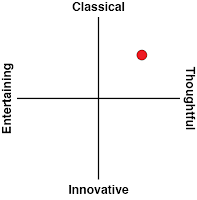

The first thing you have to understand, in order to understand the appeal of these games, is that they’re highly traditional works of detective fiction. While that might seem quaint to the point of being trite in the west in 2021 (I’m actually surprised at this localisation for that reason), these sorts of stories remain very much in vogue in Japan. Western crime fiction has moulded to hard-hitting cop drama (CSI) quirky scientists weaving modern “magic” (Bones), or even meta-heavy parodies of itself (Castle). Even when modern western artists adapt classic works in the detective genre, like Sherlock Holmes, the result tends to be big blockbuster action things, where the detective process takes second-fiddle (the Guy Ritchie films). Over in Japan, though, one of the biggest names in crime fiction is a property called Case Closed, which still sets box office records over 1,000 anime episodes and 20 feature-length films since starting. Japan has always had a fascination with detective fiction. From Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot to the home-grown detective Kogoro Akechi (check out Edogawa Ranpo’s writings), something about the genius detective with seemingly supernatural abilities to figure out impossible crimes speaks to the Japanese culture in a way that has given it longevity well beyond what the specific sub-genre ever enjoyed in the west. So, as you play Famicom Detective Club, remember first and foremost that this is a game that is very specifically Japanese in tone, aesthetic, and theme. I suspect that more than a few critics will look at it derisively for being something antiquated to our culture, but the more Japanese detective fiction you read, the more this one’s “traditional” nature will make sense.

As a game both Famicom Detective Club titles cosplay as “adventure games,” but Mages has brought very distinct visual novel-style aesthetics and sensibilities to the game that help to break that pretence down. At core it actually functions like a Danganronpa or Phoenix Wright “gateway drug” to visual novels, in that while it has a fair chunk of gameplay in it, it is, ultimately, still a VN. You’ll need to interrogate witnesses with each crime or event that you investigate, slowly learning a library of words and collecting a pile of items that you can present to other witnesses to loosen their tounges. It’s not the perfect system from a playability point of view, since you’ll often know what you need to do next, but need to work through an entire line of questioning with a witness to trigger the exact response that will progress the plot. However, I actually liked this, for two reasons: firstly, it effectively emulates the careful, precise detective process and ensures that you don’t miss important details along the way. Secondly, when you read detective fiction books, you’re always trying to figure out “whodunnit” before the protagonist does. That’s a big part of the fun of the genre. As mechanically laboured as Famicom Detective Club is, this is exactly what will happen as you play. You’re playing along with the detective tradition as you play the game, and I appreciated that way that is built into the game’s very foundations.

I would be very interested to know if the original games were as deep in the narrative as these remakes, because if so Famicom Detective Club must have seemed dense and deep back in the day. Think about it. Famicom Detective Club’s narrative peers on the NES would have been the likes of Final Fantasy 1 and Dragon Quest 1. Great games, but incredibly thin on narrative by modern standards. By contrast, Famicom Detective Club doesn’t feel like an old game remade. It’s modern and eloquent in a way entirely in line with other modern detective-themed VNs like Alternate Jake Hunter is. I would have loved for Nintendo and Mages to work together to also localise those original NES games, like Nintendo localised the first Fire Emblem last year, just to compare old and new, but I guess that wasn’t to be.

The two titles in Famicom Detective Club feed off one another (they can even transfer save files back and forth for naming consistency), but it’s important to note that it doesn’t matter the order that you play them in. Whether you experience the stories in a linear fashion, or play one as a prequel, either way, you’re not playing things wrong. And, either way, you’re going to see some of the most evocatively drawn scenes of rural and urban life in Japan. I would imagine that many that are not well-versed in visual novels haven’t heard of Mages before but I really can’t overstate how good this developer is, particularly with aesthetics. Mages is the name behind Steins;Gate, Robotics;Notes, Muv-Luv, the remake of Yu-No: A Girl Who Chants Love at the Bound of this World and Psycho-Pass: Mandatory Happiness. Mages is the developer pushing boundaries with art and animation in visual novels, and all that expertise is on full display in Famicom Detective Club. The environments are evocative and set the scene. The character portraits are exquisite and really help to drive a lot of personality through the narrative. The detective process and narrative in these games is very character-driven, so it was important that the portraits carried as much emotive weight as they have here. Indeed, as someone with a lot of experience with Mages games, I’d have to say that this is my favourite effort as far as the aesthetics go. And no, not just because the protagonist’s gal-pal, Ayumi Tachibana, is so ridiculously pretty. She certainly helps, but it’s the overall approach to the art that I love.

What I think will surprise a few people is that both of these games do have a relatively serious tone. The anime art suggests otherwise, I know, and some of the character designs really are silly. People who come to this from something like Phoenix Wright could not be faulted for expecting something similar. However, in action, both games have their fair share of grisly and intense scenes, and even the occasional moment that borders on the horrific, and this might throw less experienced players. I don’t think Nintendo’s media engine has made that quite clear enough in properly representing this. This contrast between potentially silly anime aesthetics and serious themes is a quirk of Mages as a developer (take Steins;Gate or Chaos;Child as an example), and once you’re into the game’s rhythms you can expect that disconnect sensation to disappear. I only raise this in the review so people who read it before playing the two games can be aware that the promo images of cute school girls and funny old men aren’t going to deliver the same oddball charms as a Phoenix Wright. It’s more akin to Danganronpa, where the colourful and sometimes fanservicey art masks something that the writers are asking you to think very carefully about.

Both games are relatively short in comparison to visual novels of today (thank blessed mercies for that), and you’ll knock them over in around 10 hours apiece, but they don’t come across as shallow or limited. Traditional detective fiction isn’t served by delayed gratification, and because each game features one major mystery to solve, I would suggest that if they were any longer than this they would lose steam, quickly. Perhaps the greater issue is that detective mystery, by nature, is never as interesting on a second experience – and the replay value to these games is going to be quite limited for most people. Once you know whodunnit, the only real appeal for re-experiencing the story is to investigate the way the author guides the audience to the revelations – it becomes an object for study and interest rather than something to passively consume. With that being said, both Famicom Detective Club titles are such a product of a Japanese literary tradition that doesn’t really exist in mainstream western culture, that there’s value for those with an interest in culture to run through each at least a few times to better understand an important cornerstone of Japanese storytelling.

The Famicom Detective Club games are excellent, highly traditional detective mystery stories. Some might see that as “quaint”, “old”, “antiquated” or even “simple.” That’s simply our cultural experience talking. The reality is that these games are highly relevant to the Japanese understanding and interest in the genre, and the core storytelling experience is so modern it’s easy to forget that they’re remakes of NES-era classics. Throw in some of the most stunning VN art from the very masters of the genre, and this little collection of two titles has every chance of becoming one of the sleeper hits of the year. And, who knows? If it finds the audience it deserves, it might just inspire Nintendo and Mages to make a new one. I’d be up for more Famicom Detective Club.