If you’re a fan of RPGs, you probably enjoy a fair bit of repetition. Hopefully, that’s not a controversial statement, but if you’re inclined to disagree, I have a simple experiment for you. Load up a copy of Dragon Quest (the original) and start a new game. Spend some time killing Blue Slimes a step away from the first town for one gold and one exp each (or alternatively, walk too far and get decked by a Scorpion, which is the game’s way of teaching you that the only correct way to play is to spend the prerequisite amount of time killing Blue Slimes).

How long does it take until you get bored? Or, as is the case for the millions of JRPG fans around the world, is the act of growing incrementally powerful through the act of repetition, somehow riveting?

I can’t be the only one who thinks that the modern remakes of Dragon Quest 1, horrendous art style aside, also do the original NES game a disservice by reducing the grind. On the NES, it took 20 minutes of killing Slimes and the occasional Dracky before the player would even dare wander past the safety of the first area. And as a result, the NES Dragon Quest feels like a greater achievement to complete compared to the GBC, smartphone or Switch versions. It’s not that the NES version is harder; it doesn’t require more dexterity or knowledge, but only more patience. And while “repetitiveness” is often a pejorative used by game critics to denigrate gameplay that feels arduous and meaningless, my experience with Dragon Quest goes to show that repetition is also part of what makes a game feel valuable.

This brings me to Loop Hero. I’m no stranger to repetition – I’ve finished Dragon Quest multiple times, after all – but it’s rare to see a game so brazen about it that it’s right there in the title. In Loop Hero, you play as a warrior after a mysterious Lich has wiped all memory from the world – so they need to walk around formless environments, fight enemies, get stronger, and then die, starting the entire cycle all over again.

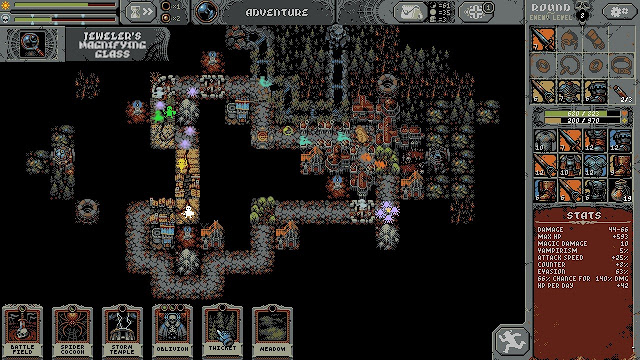

Rather than playing as the Hero and moving around a pre-designed world map, the player designs the world map around a hero who cycles through a set path. The Hero does all their combat automatically so the player’s job is just to build a formidable world of challenges to help the protagonist get stronger, and to stack on more powerful weapons and armour to make sure the Hero can handle the world of challenges you’ve made for them. If the Hero is successful, you’ll earn resources that you can use to build a township and make the next loop go more smoothly. And if the hero falls, you’ll earn 30 per cent of the resources you would have gained upon success. Either way, you get back up and start the loop all over again.

By conventional logic this setup would get boring quickly: the overall actions the player takes in Loop Hero does not vary between the first hour and the one hundredth. So why do I, and so many other critics with diverse tastes in games, all love it?

To answer that, I’ll have to expand upon my analogy of JRPG’s and repetition. Here is my argument for why every game genre is an exercise in repetition:

The only genres I could think of which don’t fall into this model are hyperactive microgame collections like Warioware, and late 90’s mascot platformers like Crash Bandicoot, Spyro the Dragon and various movie tie-ins, which shoehorned in one-off genre-switch levels with high frequency. Games are loops – with each genre having its own way of disguising them. If anything, games which aren’t loops tend to fail, because players like spending time with the game, developing mastery and familiarity. If a game kept presenting brand new experiences every time it booted up, it would feel alien and scary. For the most part, we like our games to feel cosmetically novel, but at their core, repetitive.

A game that purports to present a new experience every time, and which was uniquely alien and scary to me when I first started playing, is League of Legends. League of Legends (and all MOBA games) have dozens of characters, each with four skills, in teams of 5-on-5. Youtube ads will proclaim that no two games are exactly alike. But that’s not the story most League of Legends veterans will tell you. The game is completely repetitive: you’re playing on the same map every time, the same characters will appear over and over, and at the end of the game all progress is wiped with glory given to the winners and shame given to the losers, and then everyone queues up for another.

I am intimately familiar with this cycle.

I’ve discarded many a draft of articles arguing that MOBAs are the gaming equivalent of learning to play an instrument. Whether your poison is DOTA 2, League or Smite, the story is the same. The games are overwhelmingly complex at first, and without proper guidance and instruction, feel awful to play. Not only are your enemies destroying you, but your own teammates are also destroying you for not playing to their standard. The games are arguably the most cognitively complex thing a human being will ever do – there’s just so much stuff to keep track of at all times.

I never got great at any of these games, but I kept up the gameplay loop in the hope that one day I would. I did get better – I learned strategies, developed builds, and had some enjoyable times playing cooperatively with friends. I’ve lost count of how many hours I’ve sunk into the genre. And the reward for all my devotion is the realisation that, underneath all the strategy, the skins, the bells and whistles; these games are loops like any other – and the reward is, well, nothing.

There are, on the other hand, no real strategies in Loop Hero. There are character classes and individual builds for each class – a good early game one is Vampirism Warrior, for example, which heals faster than enemies can damage – but the game won’t stop you from progressing if you choose to ignore the strategic side of it. Whereas after my hundreds of hours in League of Legends don’t leave me with anything to show for it, I feel the achievement with every step in Loop Hero. Even if I fail, I’ve amassed a little more in the resource bank, I’ll have a better chance next time. It is a profoundly satisfying experience, precisely because it isn’t trying to hide its repetitiveness.

Resources in Loop Hero go towards a town-building menu which gives the player incremental bonuses in subsequent runs. Some buildings will give starting weapons, others unlock new potential encounter tiles, and others help you earn resources faster. New experiences are doled out in a trickle, and players need to put in the effort to unlock them. The sight of a fully decked-out town is a reward in itself – it’s a testament to the time you’ve invested, the determination you’ve applied to the task of remembering the world.

Of course, there will be the naysayers, who might say that Loop Hero is a waste of time, or just a Skinner Box. The latter refers to a behavioural experiment where pigeons were trained to peck at a button to receive food – over the course of time, they were conditioned to peck at buttons even without incentivisation. Applied to many video games, the term is an accurate description for what they are: a pat on the head for completing a menial task. But while games like League of Legends go to great lengths to disguise this reality, to the point that calling them a Skinner Box feels like an attack on the game itself, Loop Hero wears its intentions on its sleeve. Of course it’s a Skinner Box. Skinner Boxes are fun.

Lately, I’ve been noticing that I have trouble sticking to games to completion. We live in what can only be described as a deluge of content – an infinite amount of ways to spend our finite amount of hours on Earth; the exact opposite of scarcity. And as a result, I tend to play games for an hour or two and get distracted by the next big release. I keep telling myself that I need something big – a Monster Hunter or a Final Fantasy that I can sink my teeth into – but whenever I try starting one of those up I bounce right off the learning curve, or the dull prologue. Instead, it’s games like Loop Hero which have become more appealing: the instant gratification and low stakes which help me feel consistently good after a long day of work doesn’t show its immediate benefits.

Loop Hero is just a microcosm; a tangible representation of the way repetition slowly improves our lives. While we toil away at the larger narratives of our time on earth – our work, our creative endeavours, our relationships – it’s nice to be reminded that all our efforts are going towards something. Because of the world’s erasure in the story of Loop Hero, it’s reassuring to feel that every step forward the Hero takes is a step towards rebuilding; and whether that step is big or small, it has value in the grand scope of things. It’s natural to be pulled in by the game’s charms. The game’s repetition is meaningful because it’s exactly what we want repetition to be: a process by which we, slowly but surely, become better.

– Harvard L.

Contributor