At its core, NieR is a story about identity. In creating it, director, Yoko Taro, who loves to joke about philosophy being nonsense but is clearly very cognizant of the big names in the field, took the infamous “I think therefore I am” from René Descartes and spun that into one of the most layered and nuanced dissections on the topic that we’ve seen, across all art forms. Unfortunately, many people missed experiencing it on its first release back on the PlayStation 3, because NieR was an underperforming title that Square Enix never bothered to release for digital download. The series only became popular because of the sequel, NieR: Automata, and on the back of that mega-hit, Square Enix has decided to give the original NieR a second run, as NieR Replicant ver.1.22474487139… I do hope people take advantage of this, because the little bits that have been done to this game for the remaster has helped it re-take the crown as the best game ever made.

I’ll get the comparisons with its successor out of the way at the top of the review. On the one hand, NieR: Automata plays better. Though the development team have worked hard to polish the gameplay in NieR Replicant ver.1.22474487139…, this thing was infamously janky back on its original release, and there are some hard edges that simply can’t be smoothed over. NieR Automata is more fluid, dynamic, and better balanced than NieR. Secondly, it’s also a game that reaches much further. Where NieR is focused on the different implications of Descartes’ five-word phrase, NieR: Automata goes wild on the discourse covering everything from existentialism and nihilism to a deconstruction of the role of organised religion in society, synthetic life (and the various implications of that), the structure and tone of the fairy tale literary genre, and many other themes that I’m forgetting about here. NieR: Automata is the grander and more prominent work, and for that, it is arguably more important and valuable to the games-as-art movement.

However, in the latter regard, I believe that the original NieR is actually better for its more narrow focus. By being so concentrated on one key theme, this game goes incredibly deep on it. Beyond that philosophical focus, which we’ll get to in a moment, it’s also a more personal, emotive, and evocative story that speaks to the humanity in us. NieR not only tells the story of a boy and his deeply ill sister in a fading, dying world, but it also tells a lot of other little stories of other people along the way. By contrast, NieR: Automata is robotic and distant by design. It’s brilliant, but it doesn’t have the emotional impact that this one does.

Now, on to the thematic depth of NieR. It’s difficult to actually discuss this, the very core of the experience, in the context of a review, because most of what NieR is saying only comes through the various endings that you work towards, and I’m not meant to spoil that stuff for you. What I can say is this: what starts out as a seemingly simple quest by a boy to find a solution to his sister’s terminal, magical curse becomes a voyage into identity; what determines our identity as people? Is that malleable or transferable, and is identity defined by the physical, or some more esoteric concept of the spirit? Can our identity be at conflict with itself, and, ultimately, can we reject that identity? Again, none of that is going to be apparent until you’re deep into the game, and well beyond the first ending (just like NieR: Automata, this game has many endings and they’re all essential), but when those revelations do come, you’re going to be encouraged to think, and hard, about them.

Then there’s the way that the conversation around identity feeds into Yoko Taro’s thinking around dualism. Dualism is a big deal to most Asian forms of spiritual thought – think about the Yin and Yang symbol of Taoism as perhaps the most familiar example of this at work – and again, its role in NieR is going to be difficult to describe in the context of a review, but in vague terms what initially seems like opposing forces eventually becomes something much more connected and symbiotic within the world of NieR. Taoists strongly believe that what initially seems like opposing forces in the world are instead complementary. Perhaps the safest example I can give here without getting in hot water is the two magic books that are presented as the key ally and antagonist through much of the game: Grimoire Weiss and Grimoire Noir. You’re going to spend an inordinate amount of time thinking of these two as being symbolic of moral opposition – a simple case of good and evil. You’re going to find out that Yoko Taro is far too subversive for such a simple dynamic.

These ideas play right through to the small details, too. There’s the duality of two of NieR’s key allies in his adventure, Popola and Devola, who have an identical twin-but-different duality dynamic. Another character that accompanies NieR on his adventure, Kaine, is intersex (and don’t worry, that topic, and her character’s experiences, are handled with the appropriate sensitivities). NieR’s ultimate message, I think, is that identity is not simple, nor binary, and while we may well “think, therefore we are,” how we “think” and relate to the world is not as singular as people often (mistakenly) attribute to Descartes.

The most experimental game

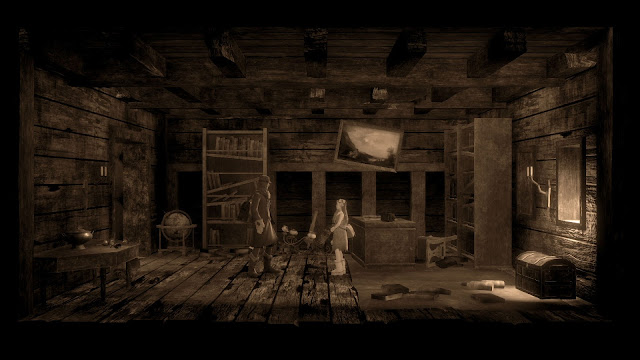

As far as gameplay goes, NieR has been well-known for its penchant to frequently “shift” genre as you play, and that has all been preserved with the remaster. While the game is nominally a JRPG, there are entire sequences that play out as top-down shooters, 2D platformers, and even – in a particularly surrealistic moment – a fourth-wall-breaking visual novel. The dungeons constantly throw new “rules” at the player to follow in this way (including one dungeon, that, in a moment of extreme self-awareness actually spells out new rules that the player has to follow as a kind of puzzle experience), and all of this comes across as highly experimental.

NieR: Automata did this too, but NieR takes it much further, and the shifts between the genres are more extreme. Just as Yoko Taro likes to challenge players to think through his narratives and themes, the structural design of NieR aims to question the threads that make up a video game; just what is genre? It asks its players. Why does “genre” matter? Would it not be better for parts of a game to play in a way that compliments that moment of the game – if one particular section has a story of significance to share, then shouldn’t that section be a visual novel? When the goal is to have the character travel through an enemy gauntlet, then isn’t the 2D platformer or SHMUP genres better suited to that? Why does a JRPG need to always conform to being a JRPG?

The highlight of NieR’s gameplay remains the boss battle, with just about every one of those being a textured, multi-stage affair against something memorable. Most of these boss battles demand that players have a good eye for identifying weaknesses and attack patterns, and while you could argue that the way that these battles are designed are a bit archaic and the industry has moved on (particularly post-Souls), there’s a quaint, classical charm to them and I found myself looking forward to replaying each of them, having some nostalgia from my original playthrough of NieR (with the added benefit that the improved frame rates and movement make these battles much less frustrating this time around).

The only thing I wish the developers would have fixed, but they’ve left untouched, is the resource gathering. As you explore the world and fight enemies, little orbs will pop into existence and, once collected, provide you with the resources that you need to modify gear and complete side quests. The problem is that some of those resources can be really quite uncommon, and this system becomes a complete grind when you start looking for the good stuff. It was an element that was probably cribbed from the Monster Hunter design philosophy back in the day, but it’s not anywhere near as engaging here, and the world is big enough, with those resources spread enough, to make you want to give up on getting some of the good stuff just to keep the game going at a reasonable pace.

Beautiful melancholia

The other really common criticism I remember being levelled at NieR, in the reviews of the original game, was that the aesthetic was too muted and grey. Consequently, just as I was worried that the developers of the Demon’s Souls remake would try and “fix” the game at the expense of its aesthetic integrity and intent, I was initially concerned when I heard that they would be remaking NieR that it would be scrubbed of its personality to make it seem prettier to the mainstream eye. Thankfully that hasn’t happened. The developers have added detail and refined character models, but NieR was always about a dull, fading, melancholic kind of apocalypse, with long views of empty, colourless landscapes, and the developer has retained that.

The hidden weapon that NieR has always had, though, and the real secret to its atmosphere, is that soundtrack. Okabe Keiichi’s score is complex and nuanced. It ranges from the delicate, with the main village theme, which aims to lull you into a false sense of serenity while also making it clear just how fragile life is in this world, through to the exotic epic theme of the desert that promises something out of 1001 Arabian Nights, and on to the heavy, industrial angst of the junkyard and its hostile robots. Because NieR is a more personal and emotional story than NieR Automata, it needed to have a more emotionally engaging, evocative soundtrack, and there’s a primal quality to the way that this score connects with the emotions that makes it almost visceral in the way it drags you into the experience.

This soundtrack is backed up by some truly inspired voice acting that lends emotional gravitas to every major character. With most Japanese games I prefer to play with the original voice cast and subtitles, simply because I find that more authentic. However, the English cast in NieR is impossible to resist. The remaster of NieR involved many of them reprising their roles for an expanded script, further deepening some of the most memorable performances we’ve enjoyed in video games.

Regardless of the protagonist, NieR is a remarkable piece of art, and this remaster touches up the issues people had with the original without compromising what made it such an impactful work. It’s going to be interesting to see if people give it the look that it deserves this time around, because this really is the greatest game of all time, and has always deserved more than “cult” status.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @mattsainsb