Review by Harvard L.

Chinese Parents looked like a harmless enough life sim. What harm could it do, with its colourful, cutesy art-style and the premise of tracing a young Chinese child from birth to their eventual undertaking of the Gaokao (the university entrance exam)? As I now know, it treads a delicate balance of being realistic without being exploitative, comically satirical without being reductive of an entire generation’s experiences. I might not have grown up in China but my parents are definitely – at least last time I checked – Chinese. But there’s some unresolved stuff that a game like this threatens to unleash: if the representation of my adolescent stress was not depicted with the utmost delicacy, I risked spiralling into a deep (deep) void.

So it’s with great relief that I can say Chinese Parents is both rather accurate, and rather fun. Funnily enough the deep (deep) void is a mechanic in Moyuwan’s simulation – if you let your child get too stressed out, their “Mind’s Shadow” takes over and you get an automatic game over. The whole game takes a gentle satirical eye to Chinese parenting styles, recognising the good and the bad, without pointing any fingers, but instead laughing and crying together in a show of solidarity.

I have the utmost respect for my parents so I’m going to be careful not to denigrate them or their parenting when I compare some of my real-life experiences to what goes on in Chinese Parents. It’s not that the game’s events are particularly outlandish or traumatic, but there is the significant cultural clash which might make them seem jarring to Western audiences. And for what it’s worth, elements of Chinese Parents clearly show the developers were trying to be relatable. Occasionally events will ask players if they relate to them from their own childhood experiences – whether it’s something as simple as cheating on a test, or something as morose as a parent forgetting to pick you up from school.

The relatability is what gives strength to what is otherwise a fairly bare-bones life-sim game. You start as a child and engage in a Minesweeper-esque minigame in order to rack-up various qualities such as IQ, Creativity, Constitution and Imagination. As you grow older, your world starts to unfold – you unlock additional subjects to study at school, additional ways to shoot the breeze, novel events which spice up the day to day, and eventually diagnostic exams to judge how well you’ve been keeping up with your academics. You could theoretically just play this game as a simulation about making numbers go up; but it wouldn’t be quite as fun as the equivalent amount of time spent on Football Simulator. No, Chinese Parents finds its strength by combining simulation gameplay with the narrative.

What I like about the otherwise contrived Minesweeper intelligence-development-game is that it combines randomness, hidden information and choice. Players can pick icons that they want to add to their character based on each stat, so they’re constantly deciding what they think is important. Special tiles provide energy or more efficient cognitive development so there’s a level of strategy to the minigame, but most importantly: it’s a game which is very possible to play sub-optimally, but impossible to play perfectly. It’s a system which forces choices, decisions and trade-offs, which does demand skill, but never outputs perfection.

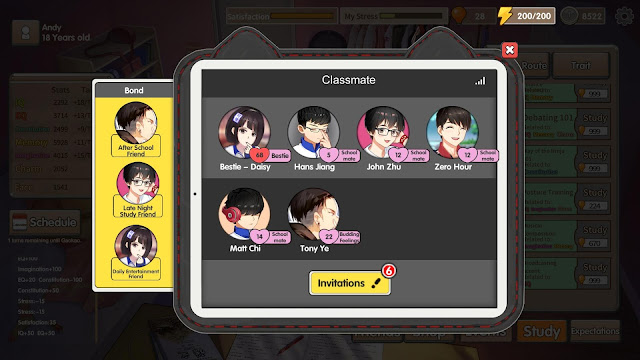

This reflects really well with my own experiences growing up. I think it’s a relatable teenage experience (not even a Chinese one, either) to be pulled in all different directions, and needing to make choices between whether you’ll prioritise study or sport, whether you’ll follow a dream or lie waiting in the wings, whether you’ll spend your time after school relaxing or planning for the future. This much I think will be relatable to anyone playing.

Where Chinese Parents gets more extreme however, is the looming Gaokao. At the bottom left of the screen, even when your child is only months old, there’s a countdown to the amount of in-game time-segments before all your efforts are assessed and your child is assigned a number which dictates whether or not they can get into a good university. And as the stereotype goes, good score leads to good university leads to good job leads to good family leads to prosperity. Bad score leads to no university leads to sadness.

As I’ve grown older I’ve come to reckon with (and very slightly appreciate) the way exams and assessments are integral to Chinese culture. The Gaokao isn’t a recent idea – before the Western world messed China up in the late 1800’s, Chinese culture had a 1500-year-long tradition of an Imperial Entrance Exam where people from all across the kingdom would pit their knowledge against each other, where the highest scoring applicants would win a seat in nobility regardless of how humble their origins. Chinese people have centuries of precedent for putting our self-worth into a written exam, for better or for worse. And while there are endemic problems with both the Imperial Entrance Exam and the Gaokao (in both cases it rhymes with “eruption”), there’s a certain it-is-what-it-is nature to Chinese culture which makes us want to succeed within a flawed system.

In your first playthrough of Chinese Parents the Gaokao will feel extremely unfair. Not only have you been picking and choosing between characteristics and then subjects only to be weighed and found lacking, but continued devotion to a half-decent Gaokao score will only result in sacrificing friends, relationships and extracurriculars in search of higher intellect. And here I need to reiterate that this isn’t a game about making strategic decisions to make a number go up. The amount of decisions the player needs to make are overwhelming, and almost all of them are the wrong one. In the first few hours I’d assumed the theme of this game was that parenthood was hard and chasing after perfection was possible, but then I realised.

You don’t play as the parents in Chinese Parents.

You play as the child.

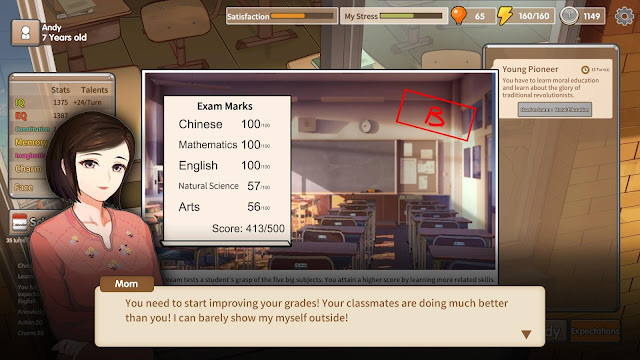

It’s a harmless enough mistake to make; you’d assume that you were playing the parents at first, scheduling crawling, listening to music and learning to talk as activities for your barely cognizant child. But as the years go by and you enter elementary school, you start to get a better grasp at the two bars surrounding your portrait in the top-left: one is “satisfaction”, i.e. how satisfied your parents are with you. And the lower one is “stress” – how much the study and pressure is taking a toll on your mental health. The game’s various activities, divided into “entertainment” and “study”, are a see-saw between honouring your parents’ wishes, and making sure you don’t over-stress and burn out. The name of the game is to schedule just enough study to not push yourself into your Mind’s Shadow, while aiming for the goals that you, or your parents, want for you – whether it’s to follow in a career path or get into a good school.

The older you get, too, the more you start to realise just how completely out-of-your-control the satisfaction and stress meters are. Sometimes you’ll just be in a bad mood and bungle a study session. Sometimes you’ll be doing great. Sometimes your parents praise you and at other times they scold you, and from what I could tell (both in-game and in real life) it had zero correlation with the numerical results I was getting from school. I knew that I could rebel in-game, to put all my energy into hedonistic acts of romantic relationships, “Starflix” and pay-to-win phone apps, but by this point I was too invested in not disappointing my imaginary video game parents. The game makes you want to earn their praise, to win the satisfaction of getting good test scores, of becoming class president, of helping your mother not lose face at the extended family dinners.

Chinese Parents lets you rejoice at your small victories – it does feel great to have a productive study session, or to make the cutoff for a particularly exclusive school. There’s an unskippable pause when exam scores are being released which will genuinely have you on the edge of your seat. You’ve made personal sacrifices for this. You’ve made choices which you hoped were the best. Have they paid off?

These victories are few and far between. As the Gaokao inched ever closer and my child was approaching their late teens, I realised that true success would be impossible. How foolish I was to think that “IQ” was going to be a realistic number: by the end of the game the expectations for my character’s IQ were in the thousands. Just as the game celebrates victories, it really makes you feel your shortcomings. The primary emotional truth of this game, morbid as it seems, is about how it feels to disappoint those who had faith in you. The game doesn’t make you hate your imaginary parents; even though they are the ones who saddle you with stress, they’re also the ones who love you and give you support regardless of how well you achieve. Chinese Parents surprisingly doesn’t have a strong opinion on the good-ness or bad-ness of this style of parenting; it only wants to show that it exists. How you feel about it is up to you to express through the game’s mechanics.

If there’s one complaint I have to make, it’s that the game doesn’t do a great job of explaining the extremely Chinese concept of “face”. Put simply, face is like an amalgamation of manners, respect, integrity and influence. Someone who has a lot of face is someone who successfully appears both modest and powerful, wealthy but not greedy, amicable but not flattering. Face can be earned, mostly through public displays, mostly by showing off how well one’s kids are doing in life. I think for non-Asian players “face” and the other specific cultural references might make the game hard to relate to. My main fear is that Chinese Parents comes off as a widget game, a “look how funny the foreigners are” pariah that’s chuckled at and forgotten.

I have no idea how a non-Chinese person might react. All I can do is be honest and say that seeing my own experiences represented in a game like this is a truly powerful thing.

For just one of many examples, there’s something so weirdly affirming about being told by the game that the goal of red packets – a Chinese New Year tradition where older relatives give the younger generation money – is actually an intricate dance of desire and refusal. In the game, you need to mash the A button at just the right cadence to simulate polite refusal of the money: refuse too little and you appear greedy, too much and you miss out on the red packet. As a kid growing up, Chinese New Year would fill me with disdain because you never quite satisfy everyone; your grandmother wants you to have the money and your parents would lose face if you accepted it too readily – so in the end it’s a power struggle with you as the bargaining chip. Chinese Parents gets this, as if the developers saw through the song and dance for what it really was.

The first playthrough is arguably the most powerful, it’s the one where the game’s mechanics still feel alien to you and you’re blundering through the adolescent years. After the Gaokao, your character flicks through their yearbook and the rest of their life whizzes by – they find a partner, settle down, have a kid. You name the kid. You play as the kid. The second playthrough sets you up with the hubris of thinking you’ll have everything planned out.

With 48 more time-blocks (frustratingly they don’t map neatly to months, or years, or seasons) until the impending exams, it’s easy to be fooled into thinking that different choices are what you need for true exam success. The reality is that it’s a lot more random than that. This does mean that playthroughs are very different, you’ll be able to explore many different aspects of upbringing over your multiple runs, and partake in some of the richness the game has to offer. Maybe in one run you’ll have a passionate summer romance, in another you’ll win a reality TV show, in another you rule as the Student Council President with an iron fist. Still won’t ace the Gaokao.

But after even more cycles, you’ll eventually get the hang of how-to min-max your baby’s stats to make him or her the ultimate test-taking machine. You’ll lament the time wasted whenever Romeos from school give you their affection. You don’t have time for their cheap chocolates – you’ve got exams to ace. It’s rather hilarious how the game’s end-state makes you just as vicious of a disciplinarian as the parents who loomed over you in your first playthrough. It’s around this time that the achievements start feeling hollow. The game runs its course, the spell is broken, you realise that it’s just a bunch of numbers crunching themselves hidden behind a veneer of real-world commentary. But somewhere along the way, Chinese Parents really did get me to reflect.

After my first ever playthrough, I’d felt pretty proud. I’d guided a toddler all the way from birth to high school graduate, picking up some friends, some knowledge, and some life skills along the way. It was my hope that she’d come out rather well-adjusted. It’s been a while since I’d been in high school, worried about my HSC score, losing my hair trying to balance my own mental health with my attempt to score the highest mark I could. I wasn’t sure exactly how accurate my performance was, at least not compared to the millions of other Chinese kids sitting the much harder Gaokao every year.

So on a whim, after I’d set my controller down and exhaled a sigh from the depths of my soul, I texted my mum in real life, with zero context, the fruits of my labour.

“Is 404 a good Gaokao score?”

She responded: “No”.

And then a few seconds later: “Not high enough to enter uni.”

Life imitates art?

– Harvard L.

Contributor

The critic was provided a code for the purposes of this review.