Retro reflections by Matt S.

These days, indie developers fall over themselves to implement “roguelike” elements into their games. Indeed, the “roguelike” to indies is what “open world” is to the big publishers – a safe and commercially-proven way of throwing a lot of content at players… and it is also so over-used and broad in scope now that it’s almost lost all meaning.

These days just about anything that has a random element in it is chalked up as as “roguelike”, but that wasn’t always the case. Back when I was growing up (I’m activating “old man yells at clouds” mode for this piece) roguelikes had a distinct quality, and in those early days of the Internet, where modems couldn’t download 3D graphics at any kind of reasonable speed – and “games as a service” wasn’t bringing us AAA-production values for free – the roguelike was one of the best outlets for gaming on a budget (i.e. when a weekly allowance wouldn’t let me buy many of the games that were sitting on the shelves).

There are two in particular that I have especially fond memories of. One is Nethack, which I believe actually has the distinction of being the game that has been in the longest state of continual development. You can download the thing for free here, and according to the website, the latest version of Nethack was actually published in March this year. Given that the very first release of Nethack was in 1987, that means that the game has been continuously worked on for 33 years – that’s some real dedication given that it’s all a community project.

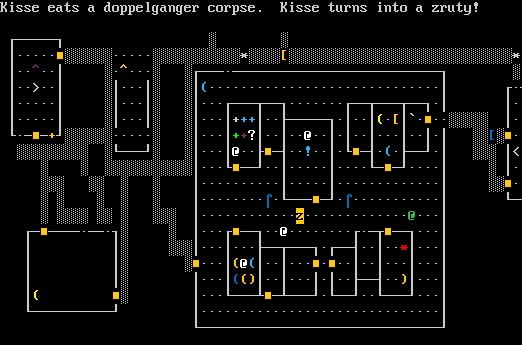

Nethack is, of course, very primitive in its presentation. The best way to play is with the ASCII characters, where your character is represented by the “@” character, monsters are various letters of the alphabet, and dungeon squares are made up of “.”. There’s also a graphical version, but it’s not that much more advanced than the ASCII version. It’s the most ridiculously replayable game, though, and has a number of features that have proven to be truly visionary.

The goal of Nethack is to get to the bottom of a 50-floor procedural dungeon, collect the “Amulet of Yendor” and then make your way back to the surface. This was incredibly difficult to do. In fact, I’ve been playing Nethack on-and-off for most of my life (and therefore the entire game’s existence), and I’ve never actually managed to “win”. The combination of random generation (meaning that it was all-to-easy to end up in an impossible situation), a rapid difficulty curve and permadeath (meaning that if your character dies you need to start right from the top) has made the full 50-floor hike a true feat of gaming. I got close, once, and got to the 49th level, but even then, I would have had to have been able to go back at the end, so really I’ve never even hit the midway point.

It’s an incredibly replayable game, though. One of the key features of Nethack is that it will save the location that previous characters have died, and then you may come across those bones on future replays. There, you can actually collect the equipment from those bones, and potentially have to battle an undead version of yourself. Play a publically-hosted version of the game, and you’ll come across the bodies of other players’ failed runs, too. These are features that we love seeing in modern games – think about how Dark Souls encourages you to try and make it back to where your character previously died – and that can be traced all the way back to Nethack.

Nethack also developed a strong community around the shared experience. Back in the days of ICQ and bulletin boards, you’d often come across terms such as “YASD” – Yet Another Stupid Death, from players that made silly mistakes that lead to their character perishing. Part of the reason that people loved chatting about Nethack so much, though (beyond the YASD jokes), is the creative freedom that the game had with how you could go about its challenge. For example, you could put gloves on, pick up a cockatrice body, and then use that as a weapon to attack enemies and turn them to stone. Of course, if you forgot to put the gloves on first you’d be turn to stone on picking up the corpse – YASD. There are few games to this day that encourage players to be as creative with their inventory as Nethack. Truly, it is a masterwork example of emergent storytelling, and an early pioneer of making video games a shared, communal experience.

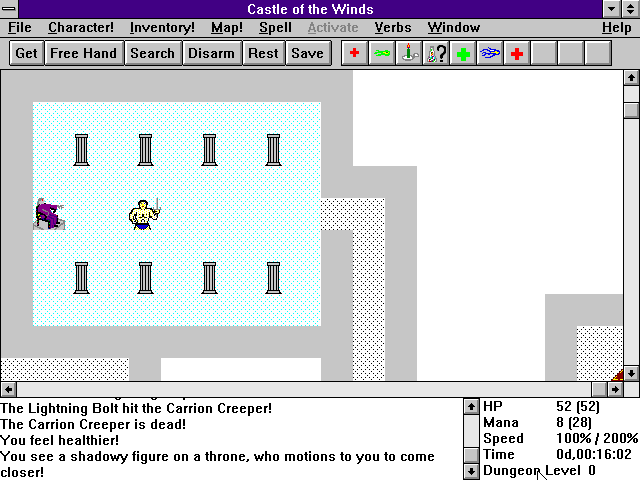

The other roguelike I wanted to mention was Castle of the Winds. I can’t remember how exactly I got this for the first time, just that it was on a 3.5-inch floppy disc (yes, that long ago), and that I only ever played the first part – A Question Of Vengence – which was released as shareware (yes, really, that long ago). The first part was massive in its own right though, and Castle of the Winds really captured my attention for its simple and childish, but oddly appealing visual design, and improved interface over what Nethack offered. It was also the slightly easier game, and I was actually able to finish this one.

What I hadn’t realised until this week is that it’s possible to play Castle of the Winds in a browser – this is a game that I had thought lost to me, but no, as it turns out, the game has been preserved. I’ve had a little putter around in it, and it’s exactly how I remember. I assume that it’s not going to be particularly resonant today to anyone who isn’t feeling nostalgic, and the fact that this stuff is free doesn’t mean as much in an era of “free-to-play”, but back in those days having freely available games that were able to occupy you for hour upon hour, and were designed around replay value was a pretty sweet deal.

What’s perhaps most interesting about the roguelike is that it really hasn’t changed all that much in the years since. It’s become a little easier, in the way that “permadeath” still means saved experience levels or some pieces of equipment, and obviously games have become a lot more playable thanks to tutorials and less confusing interfaces, but the core of what makes a roguelike what it is has remained largely untouched across the proper roguelikes that we see today. That’s one of the reasons a baulk a little every time I see indies describe their randomised level designs as qualifying the game as a “roguelike” – there’s more to the genre than that and if anyone is interested in seeing exactly what comprises a roguelike, it is possible to play the genesis of the genre and understand what the actual vision looked like.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @mattsainsb