Review by Matt S.

Note: There will be spoilers below. The PC release of Persona 4 Golden might be new, but this is a 12-year-old game at this point and I’ll be damned if I tiptoe around the game’s narrative for people that haven’t played the game yet.

Persona 4 Golden has a revenge story arc in which you can choose to throw a guy into an alternate dimension via a television because he did something terrible to a little girl that you just spent the previous 40+ hours of gameplay coming to love as little sister. Doing so will doom him, but on the other hand, he totally deserves it (as far as you know at that point in time). Nonetheless, it is a wrenchingly difficult decision to make for the sheer moral conflict that is written into the story. And, amazingly enough, it manages to be both emotionally impactful and philosophically-dense without relying on a single torture porn scene to drive home the idea that revenge can be a negative driving motivator to a person.

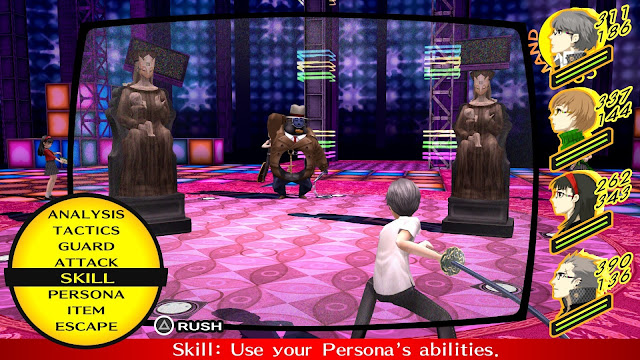

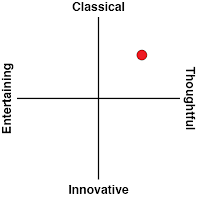

And that’s just one moment where this game proves to be a more nuanced experience than most of the AAA-blockbusters that get released today on their mammoth budgets. Persona 4 Golden really is the full package, and fondly remembered as one of the best games of all time with good reason. It’s not so much the gameplay that gets it there – the turn-based combat and randomly-generated dungeons are only fine, and certainly, Atlus would go on to figure out how to do that stuff much better by the time Persona 5 rolled around. But in comparison to its sequel, Persona 4 also proves to be the better game, and that’s because it tells a far more intelligent and meaningful story, and has a better cast of characters. This is not to suggest that Persona 5’s bunch were poor by any means. It’s just that Yu, Chie, Rise, Kanji, Teddie and the rest are all so excellent.

The biggest difference between the two games also explains why Persona 4 managed to break well beyond its peers, perhaps to an extent that the game’s creators themselves weren’t entirely aware of. In Persona 5, you’re fighting Bad Adults. Inspired by literary figures such as Maurice Leblanc’s Arsene Lupin and Edogawa Ranpo’s Fiend With Twenty Faces, your motley crew of teenagers represent the freedom fighter archetype. They see injustice and a world that is unable to deal with it, and so they take matters into their own hands. It’s fine, as far as common narrative tropes go, but it also means that the game’s bosses are all monstrous abstractions of humanity’s demons and, as tactically and visually amazing as those bosses are, they are just bosses. The kind of enemies that you expect to fight at key moments in just about every other JRPG.

In Persona 4, the enemies that you fight are far more introspective. In other words, you fight yourself. The narrative flow is as follows: a new major character is introduced, but soon disappears. The friends that form your group of heroes quickly figure out that when that happens it means that the newcomer been imprisoned into a realm that’s only accessible via televisions and, if they’re not rescued quickly, they are killed in such a way that it looks like a suicide in the real world. The heroes descend deep into the TV world each time, fighting through dungeons that are in some way a reflection of the prisoner’s innermost fears and/or internal conflicts. Then they meet the captive character, who is forced to face his/her shadow self: a grotesque mockery of their inner selves. By defeating that monster, the character can come to terms with who they are, and escape the dungeon (and subsequently join the group of friends).

One character struggles with his sexuality. Another struggles with her role in a highly traditional Japanese family and the expectation that she’ll take up the family profession. Still another girl (Rise… oh Rise), needs to come to terms with the sexualised nature of her celebrity as an idol. All of these characters are richly written, and their personal conflicts make for far more interesting and evocative dungeon crawls than the standard “let’s go deal with the corrupt Bad Adult” of Persona 5.

I think that’s why you emerge from Persona 4 caring so much more about the characters, too. Struggling as teenagers in a hostile world of adults is one thing. Witnessing a full coming of age arc, and then seeing the character become part of such a close-knit group of friends, is something entirely else. None of this is to say that the game is above criticism, and certainly, there are plenty of people out there that have noted the uncomfortable way that the game handles the portrayal of LGBTIQA+ characters and issues. Anyone that would dismiss those issues is not listing to those communities and their criticism. Nonetheless, it remains true that from the very nature of the dungeons and bosses, through to individual characterisation and how they meld together as a group, Persona 4 has been written in such an evocative, beautiful, and emotive manner that here I am on my fourth play through the game (at least), and I still find myself delighted with all its key narrative beats and following the stories of each of my favourite characters.

Beyond the base dungeons and the overarching narrative, Persona 4 has a side-story and side-quest structure that I wish more developers cribbed, though I imagine it’s difficult to do. The game runs on a calendar system, and as long as you defeat key bosses in time (to avoid a game over) you’re free to take control of the main protagonist, Yu, and do whatever else you like for the rest of your time, day-to-day. You can build up Yu’s various personal attributes which will help him in social situations down the track (much as a dating simulator operates), or you can get him to take on part-time jobs for cash (and yet more side stories), or you can grind up experience levels by revisiting previous dungeons.

Best of all, though, is that Yu can hang out with your favourite characters. Each character has a ten-stage narrative arc where they’ll eventually confide absolutely everything to Yu and they’ll become best friends for life (if you’re hanging out with a male character), or lovers (if it’s one of the girls). These narrative arcs are wonderful bits of characterisation for the sake of character depth and every single one of them is worth running through. It’s hard to do them all in a single playthrough of the game though, and that’s partly where Persona 4’s replay value comes in.

If that was all there was to Persona 4, then it would still be a wonderfully emotional ride with memorable characters and a stylish mystery plot, but there are so many sub-themes and philosophies that the game also rolls through that are well worth thinking about as you play. For one example, the game highlights the tension between small-town community and big business that was – particularly a little over a decade ago in Japan where Persona 4 first landed – a real point of concern. The local shopping street in Persona 4 is shown as derelict and dying, and that’s because a major retail mall has opened nearby. The game’s writers make their sympathies clear (you can only shop in the shopping street), but then the shopping mall – Junes – is aspirational and the game’s “little sister” character – Nanako – is enamoured with it, representing, perhaps, an acknowledgement that the old ideas of community in Japanese society are fading.

Then there’s the television motif itself, and the fact that it’s both a weapon (throw someone in there and they’re doomed) and the place where the spectacle of combat and drama occurs. Persona 4 is filled with pop culture references and tropes, and centring the action around the television acts as both an acknowledgement of the role of television to our escapism and even identities, and a criticism of it. It’s telling, for example, that technology as a whole barely plays a role in any of the social events that take place across the narrative. It’s only when danger comes knocking that suddenly technology becomes an agent.

Beyond these themes, the game also runs a gamut of pop philosophy from nihilism and existentialism through to determanism and even a dash of theology (though not related to any one particular religion, but rather religion as a concept). The game’s most significant boss in the end phase is a corrupt police detective that believes that humanity is better of compliant and ignorant than aware of the world – which is certainly a theme that has a new level of resonance in 2020. All of this is tied together via the Velvet Room – an enigmatic place that pops up in dreams and other key moments to help describe everything that’s going on in a very Jungian manner. There are so many angles to Persona 4, and you can unpack it in so many ways that it is a game that I still find myself regularly musing over, so many years after playing it for the first time. This, rather than a raw and simple kind of emotional resonance, is what game developers working on narrative experiences should be aiming for. It’s proof that games can offer a density of thought while also being engaging as entertainment (and make no mistake, Persona 4 is frequently laugh-out-loud joy, too).

The PC port of Persona 4 Golden is excellent. The character models seem to be sharpened up a bit so that they look good on larger PC monitors (in comparison to the PlayStation Vita), and it’s possible to play with Japanese voices, where the original game only featured an English voice track. Persona 4 is one of the incredibly few JRPGs that I prefer in English (Laura Bailey’s Rise makes me melt), but all Japanese games should have the native language option, and I’m glad to see it here. There’s the odd moment where the frame rate seems a little inconsistent or there’s some artefacting, but those are few and far between for anyone with a reasonably modern PC.

Persona 4 Golden is genuine, bona fide work of art, and one of those games that show the potential for the video game format to offer more than cheap thrills. It’s one of those games that you get the feeling will be remembered as a masterpiece well into the future too. With most AAA blockbusters falling out of the public discourse just a few months after release because they offer nothing but passive entertainment, it’s games like Persona 4 that we continue to discuss. Even in comparison to its own sequel, it seems to have the combination of characters, narrative, and ideas that help it to continue to be worthy of thought. We’ll still be talking about Persona 4 fifty years from now, and hopefully, it remains as accessible as this new PC release has allowed it to become.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @mattsainsb

The critic purchased a copy of this game for review.