Review by Harvard L.

I’m a firm believer that games should be diverse, and often I’ll refer to the “flavours” of games. Some games are sweet, others are spicy, some are rich. In line with this metaphor, Arrest of a Stone Buddha is very singularly bitter. As with other bitter things in life – black coffee, vodka, Vegemite – some people will avoid them, some will try to mask the flavour in order to reap the nutritious benefit, while others embrace the bitterness as part of the appeal. I’m an evangelist for this bitter game. As much as I did enjoy it, it hit a spot for me that I fully understand doesn’t exist for some other people, and in order to achieve their vision, the developer commits to design choices which could be evaluated through different eyes as “not fun”. It’s difficult to look at this game from an objective angle. But from an art criticism point of view, examining the effectiveness of the ultimate emotional impact, Arrest of a Stone Buddha is a triumph.

This game is the follow-up effort from Yeo, known for his high-school-themed existential beat-em-up The Friends of Ringo Ishikawa. Although the two games together form an unofficial “Existential Dilogy” on Steam, there’s no relation in plot or setting, and the games themselves also take different slants on existentialist philosophy. While Ishikawa was largely about the urgency of youth, the paralysis of choice and the conflict between the self and obligation, Arrest of a Stone Buddha is a much more laser-guided examination of purpose and the absurd. The stylistic theming is different too, with this outing taking cues from French New Wave cinema and John Woo action films. In Arrest of a Stone Buddha, the player takes the role of a contract killer: a steeled professional, never letting emotion or personal inclination get in the way of finishing the job. All missions start right as the protagonist draws his gun behind the primary target. The scene is still, silent. No music. The game is afoot the second the bullet is fired, at which point the player will need to guide the protagonist through the nigh-infinite mob of armed henchmen between the assassinated corpse and the getaway vehicle.

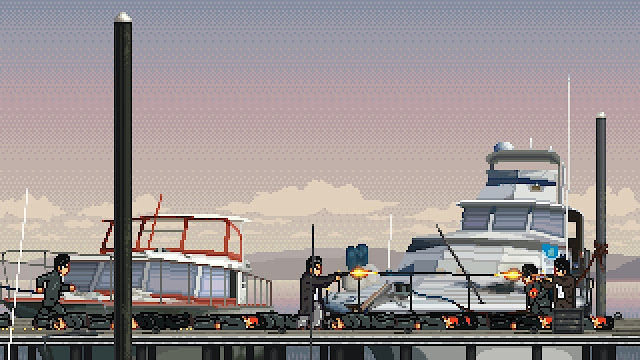

The gunplay in Arrest of a Stone Buddha’s combat segments is best described as “clinical”. Identical looking suited-thugs will walk in from both sides of the screen to impede the protagonist. It’s one-shot-one-kill with these mooks, and the protagonist can pull off all sorts of John Woo-style akimbo moves to rain death in any direction. Enemies don’t drop money or ammo or anything; guns need to be forcibly stolen from the thugs dumb enough to get into melee range, and ammo management coupled with target selection forms the core rhythm of the game’s combat. When played correctly, the protagonist is a one-man-army effortlessly headshotting throngs of goons.

The most important thing to remember in the combat scenes is to keep moving in the direction of your objective, usually the right side of the screen. The game randomly generates combinations of pistol-wielding grey-suits, shotgun-toting black-suits, and incredibly-dangerous maroon-suit-wearing snipers. At some point, you’ll get a permutation of enemies which will find you outgunned, forcing a restart of that stage. Players who want to advance the plot and not die repeatedly will need to unlearn their action-game preoccupations with killing everything in sight, and take a surgical eye to the game’s enemies to recognise which ones are walking ammo dispensers, which need to die a quick death, and what risks are necessary to escape the level unscathed.

The not-well-explained nature of the combat is understandably souring for first impressions. I’ve beaten levels on all the difficulties and there’s still stuff I haven’t figured out; namely whether you can hijack a sniper rifle from the maroon enemies who maintain their distance, whether the protagonist has a hidden health bar or whether enemies just have grace-misses on their shots. Through hard trial-and-error I’ve learned that dual-wielding pistols is the safe option since it boasts the highest ammo count; the piercing shotgun is great for moving across rooms rapidly but leaves the player vulnerable if they ever run out of shots with no mooks nearby. I’ve learned to relent from shooting anyone until they raise their gun, since they might run into melee range and let me snatch their weapon for free. The game offers an easy mode as well as more challenging difficulties, but the best experience is one where you die often, so you learn and improve.

That’s because the frustrating nature of the gameplay serves a narrative purpose: for the protagonist, it’s not a power fantasy, it’s a job. That’s why the unlockable mission select mode isn’t called “level select”, it’s “work”. And just as how many jobs in real life are not not-enjoyable, it’s possible to have fun in the combat segments, even though there’s a clear sense that it’s not designed to feel purely like entertainment. The combat is compelling, but it’s also not supposed to feel like the main attraction of the game.

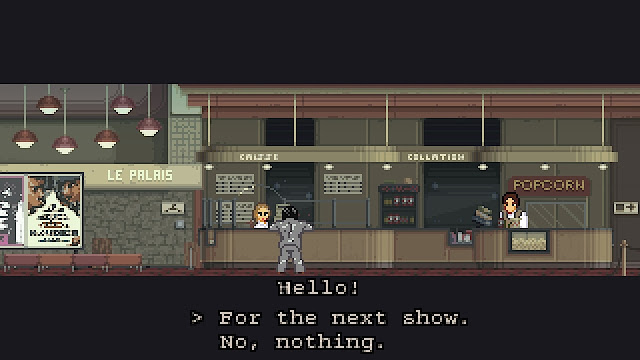

In between missions, the player is free to take their characters through a small open-world recreation of 1970’s Paris, just like the roaming of 80’s Japan in Ringo Ishikawa. These quiet reflective moments are bookended by cryptic conversations between the assassin and his handler, who passes over targets and gives vague life advice. It’s in these moments where the game slows down, and the player is given time to contemplate the nature of the protagonist they control, as well as the world around him.

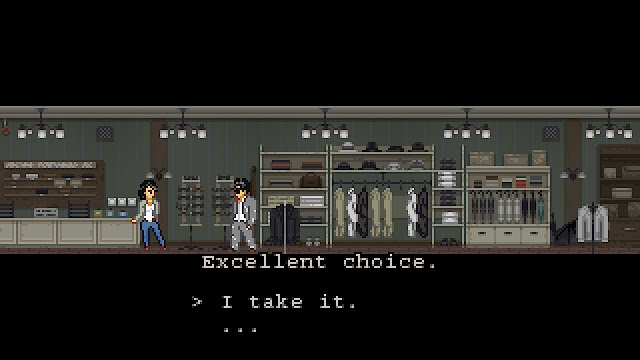

There’s a weird paradox at the heart of Arrest of a Stone Buddha’s open world roaming moments which elucidate the game’s philosophy. Like in The Friends of Ringo Ishikawa, there are many things to do in Yeo’s representation of 1970’s France. Reviewers of Arrest however have noted that the open world is empty and lifeless, which is a half-truth: the player actually has access to a huge amount of half-hidden activities. In the small block of city streets, the player can change their clothes, watch a movie, have a drink at a local café, watch the skyline from a rooftop, have a casual affair, visit an art museum, and more. There’s no shortage of things to do. But what the reviewers have noted correctly is that none of these things are particularly meaningful ways to pass the time. They are, in the grand scheme of things, flavourless.

For no matter how many pullups the protagonist does in his bedroom, how many “something strong” drinks he throws back at the café, how many minutes he spends watching the beautiful city lights switch on in real time, none of these activities have a lasting impact on him, or the player. There are no RPG systems here. No strength to be gained, no money to be earned or spent, no intelligence stats developed and tested in fun minigames. Whereas in Ringo your extracurricular activities fed into your combat prowess, gunfights and free-roaming in Arrest are completely disconnected.

It’s a powerful ludic metaphor: the fact that these activities are mechanically empty for the player mirrors the fact that they are emotionally empty for the protagonist. He’s cursed with free time that he is forced to endure, because of his insomnia and because of the lengthy spaces of time he has before work assignments. He’s tortured by the wealth of things to do, mired with the reality that none of those things has any lasting meaning.

This is coupled with the protagonist’s painfully slow walking speed, which has been the ire of many reviewers. At the first onset, I didn’t like it much either, and I found myself trying to make excuses for why it was necessary (this is probably telling of how much I liked Ringo Ishikawa, that I was convinced Arrest must be just as deliberate in its design). I thought that maybe it was significant that the walking speed between combat and leisure segments was kept constant, and the slow walking speed is required to make combat segments tense and interesting. Maybe I was supposed to be in deep reflection as I walked. Maybe the game was padding the runtime.

But as I played more and as Arrest of a Stone Buddha grew on me, I started to realise the important mechanical function that the slow walking served. It’s deliberately meant to be restrictive: getting across town is supposed to take hours, because it confronts players with the meaningless of existence in the game’s world. The protagonist can only take sleeping pills to advance days, otherwise the assignments for the game’s action segments never arrive. But sleeping pills run out, the pharmacy only opens in daytime, and the protagonist can only go to bed at night. In-between, when it’s too late to buy pills or too early to sleep, the player needs to advance time somehow. They need to do something. They’re forced into the open world, into the game’s meaninglessness, into the bitter grey days that wear down the protagonist’s psyche.

The game’s mechanics make you feel this. It’s not an angsty textbox which enables the player to distance themselves from the character speaking, it’s a set of systems designed to impart the protagonist’s frustrations into the person holding the controller. A Steam review perhaps puts it best – a player describes all the different things they’ve done in the game, asking in exasperation when something is finally supposed to start happening. And the developer only has the cheeky reply: “Yep. You captured the character’s feelings perfectly.” It makes me wonder how many of Yeo’s fans had a different interpretation of The Friends of Ringo Ishikawa, which was also ultimately an existentialist, bleak game masked as an open-world beat-em-up. To scour the reviews of Arrest of a Stone Buddha is to find Ringo-fans looking for variety, intrigue, or novelty. I’m unsure how receptive those people will be to a game which postulates that variety, intrigue and novelty are ultimately meaningless.

The run time is not much more than four or give hours, depending on how long the combat segments take and how much time the player spends messing about in the open world. Artom Belov (Wedmak2), the background artist for Ringo Ishikawa, returns for Arrest and I could honestly stare at his work for hours. Paris itself is filled with interesting locales but there are just as many fascinating screens which appear a single time for a mission and are unvisitable afterwards. The music is also varied and expressive, complementing the frenetic action and the reflective contemplation beautifully. Arrest of a Stone Buddha has impressive production values, which ensures that its emotional punches are never dulled by the means of its communication.

Arrest of the Stone Buddha sets itself apart from action titles by refusing to deliver the satisfaction inherent within a hitman power fantasy. To compare with a book which captures the bleak side of existentialist thought in the same vein as Yeo’s game, Albert Camus’s The Outsider contains relationship infidelity, a revenge killing and a criminal trial. But while those elements might make for some spicy viewing on an episode of Law and Order, reading Camus doesn’t impart the reader with any sense of exhilaration. (Take note that there is literally a copy of The Outsider visible from the game’s first frame.) When we partake in violent videogames, part of us expects to experience some base, animalistic rush that makes us feel “alive”: an artificial, fleeting high, but one which might momentarily placate our spectacle-craving brains. The same is true for films, whether it’s Jean-Pierre Meiville’s crime dramas or John Woo’s martial-arts infused gunfights (both directors who are credited in Yeo’s Special Thanks).

In Arrest, this sensation of alive-ness is undercut by stressful combat mechanics and is contrasted with bleak, meaningless open world roams. Whether killing is the only thing which makes the protagonist feel alive, it’s hard to tell; just like the game’s mechanics, it’s left unexplained. Perhaps violence robs the meaning from the world around him, or perhaps the meaninglessness of the world around him drives him to violence. As with most existential literature, the reader is allowed to speculate. The certainty though, is that there’s no escape from the situation the protagonist finds himself in. If there was an easy way out, it’s clear that he would take it, but the longer the player engages with the game the more apparent it becomes that there isn’t. Everything which might be fun, is not. Any place where meaning might be found (whether art, or romance, or nature), there isn’t any. It’s an unrelentingly bitter game, one which has the power to incite a strong reaction in anyone who plays it. Just as much as I liked it, I’m sure there are others out there who will come to hate it with a passion.

But then again, what’s worse – playing Arrest of a Stone Buddha for five hours and leaving with a negative (but powerful and thought-provoking) reaction, or playing a blockbuster for forty bland hours and not feeling a sliver of genuine emotion the entire time?

– Harvard L.

Contributor