Review by Harvard L.

We’ve all heard the old adage: “In space, no one can hear you scream”. And while that’s technically true, and while it might be effective in sending viewers to see Ridley Scott’s Alien, it’s not the most accurate way of considering extraterrestial life. You see, “no one can hear you scream” accurately captures the fear of isolation; but it holds the underlying assumption that you, screaming, calling for help, might have any sort of significance. But with the incredible scope of the universe, this is not the case at all. If you’ve ever felt small and powerless as one human in a population of seven billion, consider the insignificance of being one fleshy lifeform in a universe with far more galaxies than people in the world… the better adage might be: “In space, who cares? What even matters?”

If there is life on other planets, it would have lived and died without ever giving us the chance to witness it. This is the essence of cosmic horror – not just death, or isolation, or pain, but the full and pure understanding of our scope; of our ultimate insignificance. And that sentence rings true whether it’s from the perspective of humans, or any alien species which we statistically will never get the privilege to meet.

Which brings us to In Other Waters – a game where we get the privilege to meet some alien species! This is a game developed by Gareth Damian Martin, the editor of the games and architecture zine Heterotopias, and it follows the same art-game ethos of storytelling through virtual spaces. In this game, players dive deep into the oceanic world of Gliese 667cC, meeting its flora and fauna while trying to piece together how to survive in its unconventional ecosystem. In Other Waters is one of those rare adventure games that successfully evokes a unique and undiscovered world: you’re never noticing tropes or sci-fi genre trappings, you’re always imagining vast possibilities, and being further surprised when the game presents something outside of your wildest expectation. The way that In Other Waters achieves this though, we’ll need to look deeper for that.

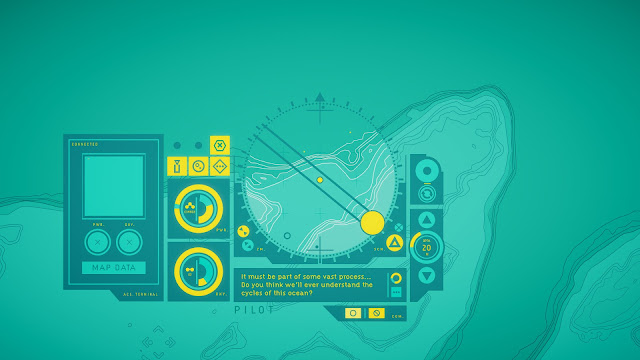

This review has started strong so far but bear with me for a moment because we’ve got to temper the expectations down a little. The actual “gameplay” of In Other Waters is relatively thin, mainly comprised of travelling along the locational nodes of a topographic map, and some occasional visual novel-style dialogue segments. Much of the gameplay interactions are done to simulate work: the interface and actions are deliberately cumbersome, and the narrative unfolds in a clandestine, scientific manner. You’re going to be very, very tempted to shut the game off before it starts getting good, especially if you’re not used to narrative-focused games, because In Other Waters has less “traditional gameplay” than arguably even a walking simulator. My very first assumption when booting it up was that I was being locked out of Gliese – I wasn’t seeing it for myself, but only in an abstraction through words and symbols. But, playing the game on its own terms, these limitations suddenly become huge strengths, to deliver a story that truly knows the potential of its medium.

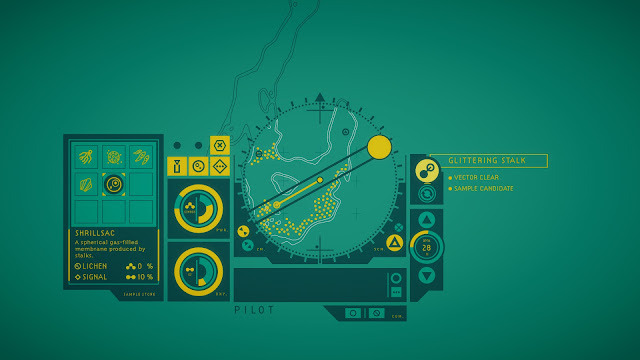

Moving around the world is frustrating because it’s meant to be. You need to hit B to activate a scanner, scan your destination point with the right stick, hit X to switch back to your movement, and then use your left stick to select the now-scanned destination, and hit A to travel. This is, effectively, a single step. A single step in a game map that takes hundreds of steps to cross. (It’s also possible to use touch controls, but because the Switch screen is small I wouldn’t recommend it unless you’ve got tiny digits).

You’re playing as an AI which controls the exploratory life support suit of Dr. Ellery Vas, so your primary functions are simply to scan the surroundings and move around, while occasionally interacting with life samples you’ve collected. Ellery will tell you what she wants you to do, and aside from a few dialogue trees, you as a player character don’t get much to say on the matter at hand at all. Your tasks as a player are to manage her oxygen and propellant levels, and all around keep her safe – your role is not to be the intrepid explorer, but the dutiful companion who discovers Gliese’s secrets second-hand.

Ellery is hot on the heels of a woman she worked with, Minae, who went missing in Gliese’s boundless oceans. The narrative develops from a mysterious beginning when you’re just picking up breadcrumbs, to one with a far greater scope that truly reveals some dark secrets about the planet. The twists and turns of the game’s plot necessitate the arcane interface; it forces the player to be acutely aware of Ellery and Minae’s limitations as human beings, and to also piece the story together from conversations and data-logs rather than having it handed to them. I can genuinely say that the lack of visuals makes the narrative a far more gripping experience: the reader is constantly pondering what possibilities or horrors exist which can’t be accurately represented through the game’s acerbic interface.

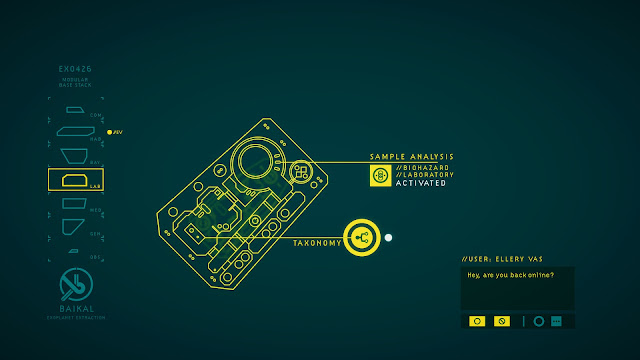

The game is quite strictly linear. Although the world map is enormous comparative to your travel speed, the various limitations and upgrades to your equipment mean that you’ll be locked in and out of certain areas. Each zone effectively instructs the player about core mechanics; for example, the introductory caves teach the player about collecting samples and activating them on the world map to reshape the environment. The player is then needed to use this skill in the next area, The Bloom, where they then learn the importance of Oxygen management, and the use of samples to replenish dwindling resources. It’s gameplay through means of increasing building blocks and menial tasks, but it also never quite feels “gamey” or contrived. Through the lens of Ellery discovering an uncharted marine world, and through the cataloguing and manipulation of [planet]’s flora and fauna, the player is constantly learning new ways to survive and press forward into deeper and darker places.

But that being said, Gliese 677Cc is still uncharted territory and, whether it means to or not, is also actively hostile. It’s possible to “die”, or at least run out of crucial supplies and thus be emergency-evacuated to the hub area, forcing you to start again from a previously discovered waypoint. This is relatively tedious as far as gameplay goes: oxygen depletes in real-game time (hope you read fast!) and propellant is used whenever you travel between nodes (hope you know where you’re going!). Environments upon consideration are cleverly designed enough that life samples could power the suit effectively, but players could also waste these samples by accident and force them to recall back to safety. The lack of an explicit tutorial is bound to frustrate some players, so just to clarify – each sample has two percentage values on it that range from around 0 per cent to 40 per cent – the top percentage is how much propellant it restores if dropped into the top tank, the bottom percentage is how much oxygen it restores when dropped into the bottom tank. If a sample restores 0 per cent oxygen and you drop it into the bottom tank, too bad; it’s gone now.

The crushing existential dread I mentioned in the review’s introduction comes through in every facet of In Other Waters’ design. In addition to the constant threat of oxygen loss or being stranded with no propellant in a dark and lifeless cave, there’s also just the constant sense that Gliese is anti-human. The various life-forms on the planet are not specifically hostile to Ellery and that’s precisely the problem. This isn’t a planet full of dangers and wonders for Ellery. This is just a planet which happens to exist, the theme is that life goes on, and whether or not humanity is a part of it is largely inconsequential. For a game comprised mostly of circles and dots, I genuinely did not expect to feel so unnerved, or so afraid.

The thing I found most beautiful about In Other Waters was how unique it was, as a sci-fi setting. It’s reminiscent of exploratory games like The Outer Wilds or No Man’s Sky – there is no need for interactivity because the whole point, the whole reward, is that the player gets to be there and witness something so perfectly alien. I noticed this each time Ellery discovered a new life form (just a garbled matrix of moving dots on my screen) – I got to read the excitement in her speech, her futile attempts to use Earth-life terms to describe the creature, and then finally being able to collect evidence of its existence: a scale, an egg, an appendage. Analysis of these samples in the game’s hub lab gives even more description to read, and then finally, a pencil sketch. But even the graphic feels paltry: it exists much more powerfully in the imagination.

I’ve praised the writing of In Other Waters a lot so far, and that’s not just because the game offers little else. With a game this text-heavy, you’d hope that the writing is good. Thankfully, Gareth Damian Martin is a master of the craft and he’s brought along guest writers from projects such as Sunless Sea: Zubmariner and No Man’s Sky: Atlas Rises. I adored the characterisation of both Ellery and Minae, and being able to see the world through their eyes was a great balance of familiarity and uncertainty. I did have my issues with the way the overall plot develops, since I thought that perhaps some narrative threads were left less explored than others. But as a springboard for imagination and wonder, the script is unparalleled.

I just wish that there were a few quality of life updates to improve the reading experience. The text size on the Switch version, whether docked or handheld, is very small, and the yellow-on-blue does hurt the eyes in long sessions. Ellery’s internal monologue also auto-advances by default, and it’s frustrating to miss text because you were busy noticing something else. (There is gracefully a Message Log function, but it’s a hassle to constantly pull up and it also doesn’t seem to work in the hub world.) I know that this wouldn’t have been feasible with the budget of the game, but voice acting for Ellery would have sent the game above and beyond. But unfortunately, the physical difficulties of reading and keeping up was the main factor that kicked me out of my immersion, which everything else had previously conjured so perfectly.

So that’s In Other Waters – a play-it-on-its-own-terms sci-fi adventure that’s enormously niche, but excels at what it sets out to do. For those who like to see hard-sci-fi, and a plausible representation of what life on other planets could be like, this is sure to be a fascinating game which will have you dreaming up theories for weeks. But be warned as well though, this is a game which demands effort from the player and isn’t afraid of standing out from genre fare. So if you’re ready to take the plunge with an open mind, the waters of Gliese 667Cc are calling, with a voice unlike any you’ve heard before.

– Harvard L.

Contributor

A copy of this game was provided by the publisher for review.