Review by Matt S.

Apparently Jon Shafer found his time working on the Civilization series to be something of a frustration. After being the lead designer on Civilization V, he left Firaxis and 2K Games to Kickstart his own game – At The Gates. At The Gates, in turn, feels like the ideological opposite of Civilization. Where Civilization aims to be accessible and intro players to the world of 4X strategy, At The Gates aims to be as complex and unwieldy as possible, so the most veteran of players can feel a great sense of reward in mastering it.

At The Gates is quite blunt about being inaccessible, going as far as to tell players that they will face a difficult game, and that it’s not going to apologise for that. That message happens in the very first tutorial introduction. That promise of difficulty is coupled with the randomisation that could place your fledgling nation immediately in the heart of an enemy horde, or an inhospitable barren wasteland, at which point the only real option is to start again. In the game, you play as one of the barbarian tribes that existed on the fringes of the ancient Roman Empire, and would threaten and eventually topple it. Your job is to be the one first over the walls. Given the might of the Roman Empire at the time, it’s thematically appropriate that At The Gates is so difficult, but in other ways Shafer seems to have made things arbitrarily obtuse just to demonstrate how hardcore his game is.

By 4X standards At The Gates is… different. It’s an interesting difference, too. You only have the one “city” for your campaign, for example, where in most other 4X titles the goal is to build and manage a sprawl of cities. It’s a kind of portable city, however, in that you can order your people to pack up and move on, and that’s something you’ll often need to do. Whereas in most 4X titles you’re looking to build a nation that can rely on static, sustainable resources, here you’ll often need to relocate as even the most basic of resources are finite, and if you tap an area out, your people will be one winter away from starvation.

Instead of growing an empire by building new cities around the place, your goal is to instead become a powerful tribe by recruiting clans under your banner. When the game starts out, you’ll have just the three, but it won’t take long for that number to grow, and as it does, you’ll need to start addressing the disparate egos of your people. Clans will all have their own priorities and preferences, and making each clan happy is an ongoing juggling act and headache. If clans are unhappy, unrest in your city starts to grow, and clans will start breaking laws and committing felonies… and how you deal with those could annoy one or more clans all over again.

Because the clans are randomly generated, one of the biggest areas where sheer bad luck can ruin your run on Rome can be getting a bad bunch of trash hanging on to your “nation’s” coattails. At other times, clans might join which have advanced skills you haven’t even researched yet, which makes the run that much smoother. I’m not a big fan of random stuff taking success out of the player’s hands, but Shafer’s vision of roguelike-style randomisation applied to 4X strategy is impressive in its gumption, whatever its flaws.

There has obviously been a lot of proper historical research that has gone into the creation of At The Gates to reflect the culture, movement and lifestyles of Rome’s rivals. The barbarian people didn’t build empires in the way that the “west” (including Rome) did, so the traditional approach to 4X strategy was never going to work. Instead, structuring the game around competing dominant personalities, the need for each “clan” to be trained up in skills around military, hunting, and foraging, and the semi-nomadic lifestyle is more accurate to how these people lived, and it forces a re-think about just about every level of strategy that we would take for granted in the more standard, colonialist-approach 4X strategy titles.

The science and skill trees are ridiculously complex, and quite poorly defined and explained, so having the right “path” to unlock talents for your people is another area where you’ll need to settle in for some good, old-fashioned trial-and-error. There is a nice sense of reward in the visual of having dozens of tribes using your base city as the hub before they spread out to all corners of the region to tackle their own individual goals, and unlike something like Civilization, where units work largely independent on one another, there’s a nice sense that there’s an invisible web connecting all of your units in At The Gates, which makes each and every unit feel like it has some kind of value to the overall cause. Even if the tribe that units represents have an attitude that makes them a real drag on the rest of the tribe.

That sense that a community is working together towards survival is further emphasised once winter hits. At The Gates runs a full seasonal system, and during the winter, you’ll be looking at a few months of snow covered land that is almost impossible to generate ample food from. Instead you need to make sure that you’ve got enough stockpiled from the better weather months to sustain your tribe and avoid starvation setting in. For a 4X game, At The Gates does do a remarkable job of characterising everyone that you see on the map, and making you see them are more than statistics and tools to be exploited.

Learning At The Gates is something that simply requires persistence, and a willingness to fail a few times. It does feel rewarding when all the various systems start to make sense, and you start to approach survival and tribe development with efficiency, though it can be a painfully slow process of waiting for many turns for things to happen. This game takes “slow burn” to a whole other level, in that the exciting moments in At The Gates do take a long time to build up to, though the time frames of each single campaign are relatively constrained and you can knock off a campaign in a solid weekend’s play.

There are a few things that really let the At The Games vision down, however. For a game that’s meant to be challenging and unforgiving, most of that challenge comes from the elements. Rival clans, which by all rights should be an ongoing thorn in any barbarian mob’s side, are remarkably passive, and Rome itself actually suffers a historically-accurate but challenge-killing decline in power towards the end of the game. If you’re able to hang around and weather the elements to the point that you’ve got a stable “nation” and a reasonably competent military, you’ll roll over everything in the late game. Diplomacy is also under-utilised and overly-simple. I’ve always found diplomacy to be the side that developers of 4X games struggle with the most, because it’s the part that needs to emulate a complex side of human behaviour. However, there have been better attempts at it than the light touch, and nearly irrelevant approach that At The Gates takes.

There’s also plenty of bugs, an user interface that is anything but intuitive (again, it appears to have been made more complex for the sake of giving hardcore players something to feel good about mastering), and the tutorials are wordy without necessarily being helpful. At The Gates is certainly in a raw state right now, and while Shafer has promised that there are updates on the way, it’s hard to escape the sense that he has made the game he wanted to, and all that inaccessibility will only ever be addressed in a very superficial sense. I’m confident in making the prediction that At The Gates will never work as an introduction to the genre.

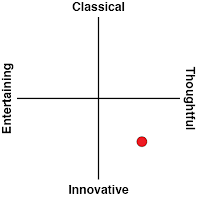

For those who do understand their 4X genre, however, At The Gates will come across as a breath of fresh air. It’s a ground-up rethink on how the genre can work, and what the 4X might look like as applied to the many cultures and civilizations out there that didn’t have the imperialist intent that most 4X titles assume. For that, it’s one of the most interesting strategy games I’ve played in years.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

Please help keep DDNet running: Running an online publication isn’t cheap, and it’s highly time consuming. Please help me keep the site running and providing interviews, reviews, and features like this by supporting me on Patreon. Even $1/ month would be a hugely appreciated vote of confidence in the kind of work we’re doing. Please click here to be taken to my Patreon, and thank you for reading and your support!