Opinion by Harvard L.

Yesterday, in my Smash Bros. burnout, I decided to revisit Yonder: The Cloud Catcher Chronicles on the Switch because I thought it would be one that could relax me. Unfortunately, stepping back into Yonder after a break was confusing at first – I dropped into the picturesque game world with twelve quests on my compass and I couldn’t remember which ones I was able to do, and which ones I had become stuck on and left for later. I couldn’t remember what it meant to cut down trees (would they grow back?) or how to fish (did I need bait?) or how the game’s economy system worked. While I thought Yonder was, and still is, a great game, it’s one which requires player commitment, and it’s hard to revisit once you’ve put it aside for too long. I spent the time being more confused than relaxed, but I instinctively remembered another game that I could immediately pick up and get sucked into: and that game is Proteus.

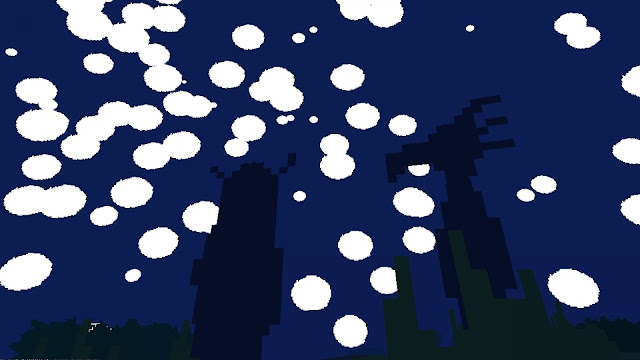

Developed by Ed Key and David Kanaga and released on PC in 2013, Proteus’s protracted five-year design period reflects its small team and its lofty ambition. It’s an open world game, but one paired right back, and what has remained is purely the exploration, with not many other systems to speak of – there were no characters or dialogue, no direct storyline, no side quests, no objectives, achievements, combat system, crafting system, levelling system or progress tracking whatsoever. What was left? Just walking, seeing and listening. Around this simple core, the developers created an ecosystem of pixel-art animals and randomly generated hills, rivers, mountains and islands for the player to explore.

Compared to most other games that we would generally consider to be examples of the “art game” genre, like Dear Esther, Gone Home, Shadow of the Colossus, or Journey, Proteus feels most like something that would feel most at home as an installation at a modern art museum. The other games I have mentioned draw from indie films and other conventional narratives, but Proteus is primarily an experience to be considered and contemplated for as much time as the player feels appropriate. It is an experiment of space, colour, light and sound; procedurally generated and wholly unpredictable.

Let’s set the scene though – in 2013, when Proteus first released, the indie game movement had been properly alive and kicking for a few years. The term “walking simulator” had already been coined, but it was less of a genre defining term for new games and more of a derogatory way to criticise a perceived lack of interactivity (and therefore, the reasoning went, the qualities that make a game a game). Meanwhile, the triple-A open world experience that is now almost the default was just starting to find its legs, with games like the third iteration of Far Cry and Assassin’s Creed, and later GTA V, moving the contemporary vogue away from FPS campaigns and more towards a world of “stuff” to do.

If there was any metric for the success of a game in this era, it was this “stuff”. Players hadn’t yet gotten burnt out on climbing towers, liberating encampments, finishing missions and unlocking loot. Games were bought one-by-one, and finished one-by-one, and the developers built around this assumption too. Just take a look at some of the opening sequences of games from this era – the hand-holding via waypoints and obtrusive popup windows is obnoxious, and serve as a calling card for a design philosophy that insists players know what they are doing and where they are going at all times. All of this belies the values of a gaming audience which would sour at a game like Proteus, which goes out of its way to be devoid of tasks, achievements or milestones in its desire to let the player truly wander. It comes as no surprise that early Metacritic reviews from critics are confused as to what exactly to call this game, and that player reviews tend to deny that this is a game at all.

But everything about that is different in 2018. One of the most apparent is the decision by both indie and triple-A developers to loosen the reins on their games a little and let players get lost in the worlds they have built. We see this ethos in everything from Red Dead Redemption 2, The Legend of Zelda and indie games like The Witness or Hollow Knight. These are games which, although they do still feature laundry lists of collectibles and side missions, do not treat wandering around as wasted time. They are happy to let players stumble upon the next objective by means of environmental design or curiosity rather than big glowing signposts. While I doubt that many – if any – of those games was directly inspired by Proteus, the positive reception to this more open design owes a lot to experimentation from the indie scene by, among other things, walking simulators.

The way we purchase games has also changed. In 2013 the industry was at a crossroads between physical copies and digital downloads, but now with the robust online stores on all major consoles and handhelds, digital seems to be the way to go. The frequency of online sales and services like Humble Bundle mean that we’re buying and playing multiple games at once. Subscription services like Gamepass and PS Plus, the latter of which even offered Proteus for free at one point, provide even further opportunities to try a game that the notoriously risk-averse video game fan will know little-to-nothing about – nothing closes a user’s wallet in video games quicker than the potential that they don’t know enough about a game and therefore might not enjoy it, but subscription services are a way around that.

As such, I feel that in today’s climate, it’s much easier to enjoy a game like Proteus than when it originally released. It’s a game which works well in short bursts, and for any player who has enjoyed wandering around aimlessly in a big open-world title will surely “get” the aesthetic that Ed Key and David Kanaga were going for. Proteus is a great game for relaxation or de-stress, especially when the player wants the sense of exploration without having to contend with random encounters or hostile wildlife. It’s a game for when you are done with “games”.

Looking at some of the early reviews, it seems that many writers struggled with the concept of replay value, suggesting that there is little to do in Proteus, and thus it is short. But look deeper and the question is more complex than it first appears. Yes, Proteus is a game with an ending (you’ll need to transition through all four seasons) and it doesn’t take long to reach it, but it’s also not entirely a game about reaching its ending. If asked “how long is this game”, I could very reasonably answer “as long as you want it to be”. In another sense, the ending is when the player gets tired of the game and decides to not play it again – for some this could be five minutes, for others it could be when they have seen every creature and interaction the randomly seeded island can generate, and for some it will be even longer than this. I don’t think many players would interpret game length as this, but perhaps this is another one of those medium tropes that will one day change.

Is Proteus a perfect game? For many reasons, no – but it’s still one that deserves attention, both when it first released and in today’s context. Any designer will be able to tell you that half-failures are far more interesting than successes. In an industry vulnerable to stagnation, it’s increasingly become the domain of indie developers to probe new ideas and take risks on design choices that go against the assumptions which become ingrained into the bigger studios. It may not be the most lucrative or glamorous endeavour, but it’s an honest one, and certainly necessary to help the medium continue to grow in the long term. It would be a real shame if we never saw something as polarising as Proteus again.

So I’ll leave you all with this: in 2019, make a commitment to pair every blockbuster game you buy with a purchase of a mixed-reception indie game at full price. Pursue games that look strange and confusing to you and love them, hate them, write about them, and remember them. If nothing else, it will bring reassurance that there are still creative minds hard at work in the medium, and that every deep-rooted trope of modern gaming will be subject to change in due time. Here’s hoping to an unexpected, strange and beautiful 2019.

– Harvard L.

Contributor

Please help keep DDNet running: Running an online publication isn’t cheap, and it’s highly time consuming. Please help me keep the site running and providing interviews, reviews, and features like this by supporting me on Patreon. Even $1/ month would be a hugely appreciated vote of confidence in the kind of work we’re doing. Please click here to be taken to my Patreon, and thank you for reading and your support!