Interview by Matt S.

Yamanaka Takuya is the perfect example of the benefit of having the director of a video game come from outside of game development. Young for a game director, and appearing more like an indie rock musician than game developer (which is amusing, because he shares a name with an actual indie rock musician), Yamanaka is the creative force behind The Caligula Effect, and we spent most of the interview time that I had with him at Tokyo Game Show talking about philosophy and psychology, rather than the joy of pressing buttons.

“I started out studying psychology. I wanted to be a counsellor,” Yamanaka said. “A lot happened, and I ended up becoming a game director. When I got that position, the first thing I thought was ‘what can I make that other people can’t?’

“That’s where I thought to expand on my background in psychology, and use it as the basis of The Caligula Effect. The core theme of the game is that feeling of guilt and excitement that comes from doing something that you’re not allowed to. I call that ‘the Caligula effect.’ And that’s how we ended up with the concept for this game.”

That might be the general concept of the game, but that’s just the surface. Scratching beneath that reveals a game of layered themes and nuance, and at the centre of it all is Hatsune Miku.

Making a JRPG about a vocaloid

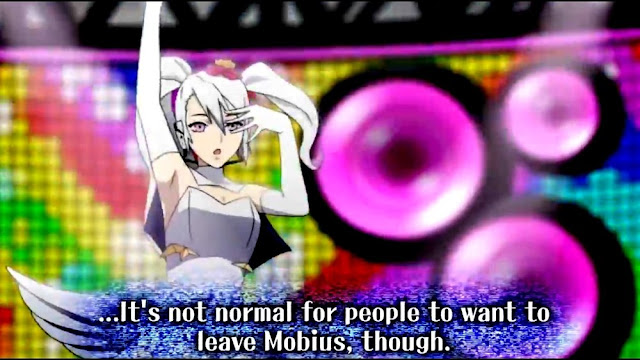

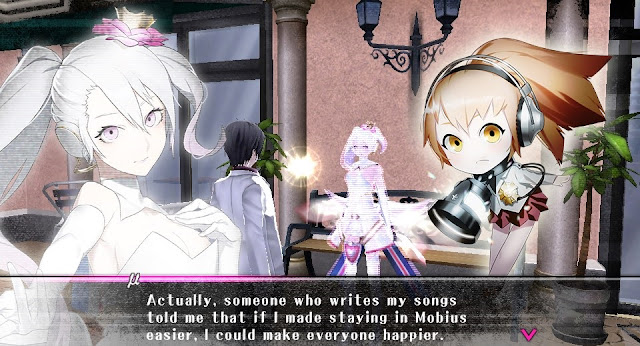

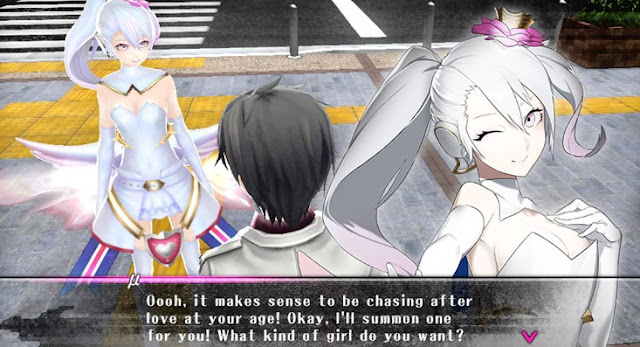

The Caligula Effect depicts a virtual world, free of the difficulties of life, that people escape to, and lose themselves within. In denying reality they find peace and harmony… but naturally they do so at the expense of their ability to interact with reality. Central to this world, and its creator and God, is the digital superstar singer, μ (Mu).

As the player, your job is to lead a team of ‘woke’ heroes in their bid to defeat this God and escape from her universe back into the real world. Your opposition are the people who are quite content with the virtual world they now inhabit.

Yamanaka confirmed by suspicions about μ from my own play-through of The Caligula Effect; she is indeed modelled closely on Hatsune Miku.

“In Japanese spirituality and folklore, there’s a common theme in the concept of humans fighting against gods and defeating them,” Yamanaka said.

“It was an appealing narrative theme because it’s something that was very taboo, of course, and as such a lot of people found the idea fascinating. But lately, people in the current era, they don’t believe in gods anymore, and they’re moving more towards worshipping idols or famous TV stars. People are more inclined to believe in them instead of a god.

“So we can see that Hatsune Miku is a kind of saviour and being to believe in for the young people in the current era. If you take someone like her and actually defeat her… well, that would be the equivalent of god killing of this era. That’s how μ came about.”

Yamanaka isn’t the only one that has mused on the potential implications of people finding a kind of god-experience in the digital realms. A few years ago, a Japanese artist named Hiroshi Sugimoto created an exhibition called the Lost Human Genetic Archive; an installation that depicted a couple of dozen apocalypse scenarios. To go with the obvious depictions of meteor strikes and nuclear warfare, there was a scene depicting Hatsune Miku.

The scenario there was that because people no longer felt the need to interact with other “real” people, the worship of digital celebrities drove a plummeting birth rate, and from there a host of socio-economic challenges that ultimately lead to the collapse of society.

The scenario is no more far-fetched than that of nuclear warfare or a meteor strike. There’s a term in psychological science called supernormal stimulus; defined as a stimulus that elicits a response more strongly than the stimulus for which it evolved. Or, in other words, it’s something that’s better than the real thing. Observations of supernormal stimulus in nature show that the stimulus tends to replace the real interaction – there’s a famous example of a beetle in Australia that nearly went extinct because the male version of the beetle found a certain kind of beer bottle that was commonly discarded on the road to be a more perfect mate than the actual female beetles.

And then there’s the news that in Japan – the country with the most supernormal stimulus for humans, the youth aren’t just avoiding having children… they’re simply not having sex at all.

As per the article: “One woman, when asked why they think 64 per cent of people in the same age group are not in relationships, said she thought men “cannot be bothered” to ask the opposite sex on dates because it was easier to watch Internet porn.”

Pornography is considered a supernormal stimulus.

Above and beyond this, Yamanaka, is also interested in the communities and cultures that form around Hatsune Miku; how they work and interact with one another. Equally, he is also fascinated by the way those from outside of Miku’s sphere look into those sub-cultures.

“It’s been 11 years since Hatsune Miku came out into the world,” he said. “There’s enough there that we can talk about her in a historical sense now, and Miku has created a very interesting society for young people nowadays because they can communicate through her using songs and lyrics created by themselves.

“I was in college when Miku first arrived. I enjoy her, but more than that, I also observed people who didn’t understand the society that liked Miku, and they would look in at the community with a very cold stare. That was a really interesting phenomenon that was happening around me. The difference between those two societies has been something very interesting to watch over the years.

“That turned into another theme that I wanted to put into The Caligula Effect,” Yamanaka added. That’s how the game’s world – Mobius – came into being, and the heads that actually control the area (the bosses) came about.”

On subverting expectations for the Japanese anime hero

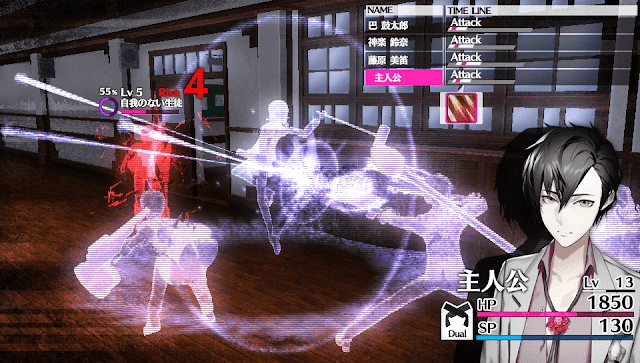

When it came to building the team of heroes that players would guide through this utopic trap of a world, Yamanaka was heavily inspired by a particular quote from Nietzsche: “That which does not kill us, makes us stronger.”

“In Caligula, each of the characters that form the heroes are damaged by certain things in their backgrounds, and those things that actually damage them end up becoming their weapons. In that way, that famous quote from Nietzsche is present in Caligula,” Yamanaka said.

That theme is common enough. Famously the Persona series has made very good use of the exact same theme over quite a few years now. And indeed, Caligula can be superficially compared to the Persona series.

The difference is that in Caligula, the “heroes” aren’t really heroes at all.

“The way I visualised it was that in Caligula, the idea that a person’s trauma becomes their weapons, it’s like this black ball of terror,” Yamanaka said. “That blackness you could say is human skin or the outline of humans. When put in a stressful situation, that blackness comes out to break the surface, and that’s when we show who we really are.”

This is why the characters actually take on a sinister air when the weapons emerge. Their face masks and colourful designs offer an unnatural contrast to the minimalist and whitewashed world around them, and this was Yamanaka’s way of telling players that it was better to sympathise with them as anti-heroes, in comparison to Persona’s heroes.

“Caligula’s protagonists aren’t really interested in justice or what is right and wrong,” Yamanaka said. “They’re not trying to save the world. They’re just trying to save themselves. It’s a selfish response.”

In fact, Yamanaka’s subversion of the traditional JRPG hero goes further than that. It applies to the party dynamics as well. JRPGs – and indeed the broader anime and popular storytelling space in Japan, is absolutely dominated by the concept of ‘nakama’ – a deep bond formed between a group of protagonists that goes well beyond simple friendship. Persona is the very epitome of the term, with each game being entirely built around deepening the bonds between the main character and the rest of the group they draw around them.

The Caligula Effect is the opposite. The characters don’t really care for one another on any meaningful level.

“They simply happen to be heading in the same vector,” Yamanaka said. “I never wanted them to be close or best friends. That’s what gives this game a different flavour and a different atmosphere than a lot of other games.”

The Caligula Effect has such a different tone and atmosphere, in fact, that one of the more odd bits of feedback that Yamanaka got was that many players had no idea who to relate to. Players are encouraged to delve deeply into the backstory of the characters that they find most interesting and relatable, but figuring out just which characters that is can be an alienating process for anyone looking to use their existing understanding of anime to figure out. That’s not just because the characterisation broke boundaries through the narrative, but because the anime and Japanese game industry has character design ‘rules’ that are for all intents and purposes the law of the medium. Yamanaka wanted to break them all.

“The cool guy has blue hair, the girl with red hair gets angry easily, and so on,” Yamanaka said. “I quite specifically wanted to avoid those really typical categories that everybody has. There were a lot of long discussions with the artists about that.

“It worked, though. People came to me and said that when they first played the game, they couldn’t tell which character was which because they weren’t neatly fitting into those categories,” he laughed.

“But I think that because we did that, the people who did fall in love with the game really fell in love with it. So much so that sometimes we’ll receive birthday cards for the characters on their birthdays. This game isn’t a AAA title, so in a good way we haven’t been pressured to make it something that everyone will love, and because of that we’ve been able to make something that has really resonated with some people deeply.”

Perhaps the greatest subversion of all in The Caligula Effect, however, is the real centre of everything, μ.

“At first, internally everyone on the team was against this,” Yamanaka laughed. “So of course I ignored them all!

“Because μ ends up being this character who fulfils everybody’s wishes, but in doing so ends up ruining the world, I felt it was absolutely necessary from a symbolic point of view that everything about her would be white.

“The original candidate for her design was actually much cooler than what she ended up being. My idea was to make her this young girl who’s very cute, and looks delicate. Because Caligula’s a game where it’s essentially you want to do what you shouldn’t do. It was necessary to have her be a character that was really hard to kill.”

How many other JRPGs can you think of that make the ‘final villain’ look so pure and innocent, and be that much easier to empathise with?

Japan’s next subversive JRPG specialist

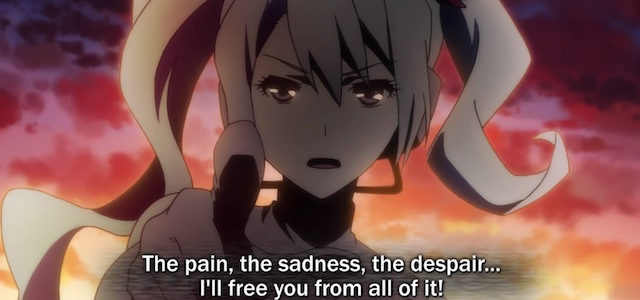

Yamanaka was also responsible for the direction of The Caligula Effect anime, which does take a different approach to the storytelling when compared to the game.

“One of the fundamental design flaws of so many animes based on games is that the instant you start to produce the anime, you move agency away from the player, who used to have to be able to make choices within the game. There is no player. It can fundamentally change the tone of the anime,” Yamanaka said.

“To solve this problem, we talked with the anime staff carefully and the solution was to create an original character… and that character is the one with the agency. Because that character is doing the acting, someone who’s already familiar with the game knows not to expect the character to make the same choices that they would have, so they don’t feel like the story is at odds with their vision of The Caligula Effect.”

Yamanaka isn’t done with many of the ideas that he has explored in The Caligula Effect, though he’s quiet on whether there’s the potential for a direct continuation of this particular franchise. “As the world continues and as new developments are made in society, there’s going to be new issues that people face,” he said. “Within that, there’s always an opportunity to create more ‘Caligula’, and develop situations to play out through games. There’s always fertile soil there to do something else.”

The Caligula Effect, on its initial release on the PlayStation Vita, was roundly criticised, more for its technical issues than any particular analysis of its narrative and themes. However, in Japan, the upcoming ‘HD Remaster,’ for PlayStation 4 and Nintendo Switch, The Caligula Effect: Overdose, has been received better, and sold significantly better.

It’s a good sign for the game’s release early next year in the west. As Yamanaka noted, this game doesn’t try to be a mainstream hit, and subversive games are always polarising. But then, you only need to look back at the original NieR, which was also roundly criticised until people, after playing NieR: Automata, rediscovered it and started to appreciate it for its narrative strengths over its technical weaknesses.

Yamanaka may well be the next Yoko Taro, because The Caligula Effect is the most brilliant JRPG that most people overlooked.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

Please help keep DDNet running: Running an online publication isn’t cheap, and it’s highly time consuming. Please help me keep the site running and providing interviews, reviews, and features like this by supporting me on Patreon. Even $1/ month would be a hugely appreciated vote of confidence in the kind of work we’re doing. Please click here to be taken to my Patreon, and thank you for reading and your support!