Review by Matt S.

South Korea’s high performance culture has some unfortunate side effects; the expectations placed on its people leads to exceptionally high levels of pressure and stress on individuals, and when things go wrong, they go really, really wrong. Nowhere is this more evident than in the nation’s school system.

Now, South Korea takes a great deal of pride in the results it gets out of its school system. Statistics show that it is the most literate nation of all, in the top five for both science and mathematics education, and over 80 per cent of Korean students go on to tertiary education. An educated population is a good thing, especially in the context of a democracy where people’s opinions can and do affect the future direction of the nation.

Indeed, the commitment to education has been a big reason that the country has managed to take its relatively small population, geographic size, and minimal natural resources (and an economy that was ruined following World War 2 and the Korean War) to become the 13th largest economy in the world. But there’s another side to that. The expectations placed on students to perform in the classroom has also led to the country having the highest suicide rate of children aged between 10 and 19. It’s not a country where people feel like they have the room to make mistakes, it’s not a culture where there are awards for participation and effort (without results), and while that has created a culture of academic and intellectual rigour, it’s also an environment that is stifling, demanding, and, tragically, too many young people struggle to cope with that.

The Coma kicks off with a young teenage boy going to school, stressed in the extreme over upcoming exams, and the first thing he discovers on arriving at the school gates is that one of his classmates has attempted suicide. Then the boy dutifully heads off to his exam, because despite the suicide, most of the rest of the students are carrying along as normal, and are only concerned with their studies, such is the normalisation and dehumanisation of suicide in such an educational culture. At the exam, our young protagonist falls asleep. He wakes up to discover that he’s now in a horrific nightmare where the teachers are trying to kill him. This is how The Coma begins.

Developed by a Korean developer, The Coma is clearly analogous to the experience that real Korean kids go through, the nightmare world metaphoric to the hostility and sense of desperation in the students that the system perpetuates. It’s hardly subtle about it, but it’s effective enough at highlighting a genuine challenge within the developer’s culture, and indeed those real-world implications of the game help make the horror really hit home. Horror is at its most effective when it’s performing as some kind of mirror or metaphor for real world events. It’s just a pity that the game itself only manages to be decent, without really supporting the game’s strong theme.

The Coma is a 2D stalker horror game, in which your capacity to actually fight back against your enemies is almost non-existent. You’ll spend most of this game wandering around the environment, solving simple puzzles and roadblocks to reach the next section of the school and progress the story. Periodically, an enemy will pop up and chase you, and which point the only way to survive is to flee and find a place to hide like a toilet stall or closet. There you’ll stay until the stalker has wandered away, hoping that they hadn’t spotted you slipping into the hideaway.

This is my preferred kind of horror. From the classics such as Haunting Ground and Clock Tower 3, right through to more recently released examples such as Amnesia or Yomawari, I find the disempowering nature of stalker horror – the inability to fight back and the lack of security from not having access to weapons – is more true to the nature of horror than most of the games that do give you the capacity to fight back – games like Resident Evil or The Evil Within. So on that ground, The Coma works for me. In fact, as a 2D stalker horror game it actually plays very similarly to Creeping Terror, a game that I think was one of 2017’s most horribly overlooked and under-appreciated titles.

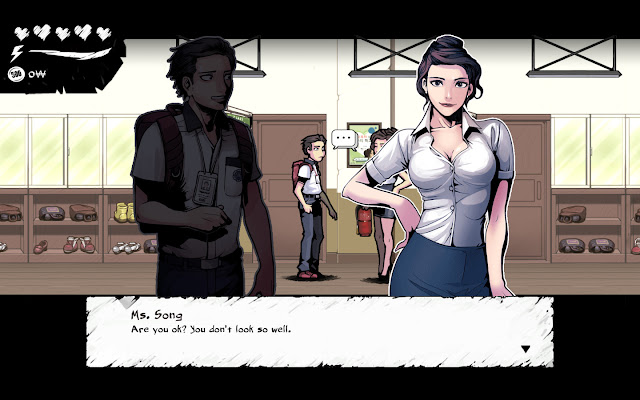

But The Coma struggles to take its great concept and really execute on it. One of its most critical failings is its aesthetics, which fail to construct the tension that horror really needs to be effective. Character portraits that pop up whenever a conversation happens have a generic anime quality to them; the lines are clean, the boobs are massive, but most critically, the designs themselves are nondescript. You could take those character profiles and stick them in a school-themed RPG Maker project, and they’d look entirely appropriate for it. Anime art and horror can go well together – look at Corpse Party as an example – but it can’t be as plain as it is in The Coma, because horror relies on players forming an attachment to the characters, and I didn’t really care about any of this cast.

The school itself is equally nondescript. Your protagonist is exploring it at night, and only has a flashlight to highlight the long corridors and unending class rooms as he goes, but the developer doesn’t do enough to play with light or environment design to tell a story of its own. Almost everything you learn in The Coma is explained to you either through character interactions or notes that you find lying around, and while the implications of these bits of storytelling are horrific enough, there’s very little done in the environment to reinforce it. You could argue there’s something faintly worthwhile and thematically appropriate about the school environment being so sterile contrasted against the horror going on over the top of it, particularly given the cultural context backing the game. If that was the developer’s intention, however, it wasn’t implemented anywhere to the kind of depth that it needed to be.

The game plays well enough, but it’s difficult to get really into the tensions of the chase or the survival experience when you’re not particularly invested in the protagonist’s plight. As mentioned earlier, when a stalker jumps out at your protagonist, his only real option is to run and hide. You’ve only got a limited amount of stamina to work with for actually running away, and you’ll need to conserve that energy and find a safe place as quickly as possible, because the stalker does get closer if your character isn’t running. There’s also a dodge button, but actually timing that can be difficult, so it’s something I tried not to rely on much as I played.

The Coma doesn’t outstay its welcome, and tells its story over five or so hours. Sadly it’s just not frightening enough. The implications of the story it’s telling are terrifying, and certainly this will discourage anyone who thought they wanted to do a couple of years education in South Korea, so the themes that form the basis of game are potent. But where Creeping Terror had me gripped with its aesthetics and tension and never let go, The Coma is simply too inconsistent and clean to really work as a piece of horror.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

|

| Please Support Me On Patreon!

|