Review by Harvard L.

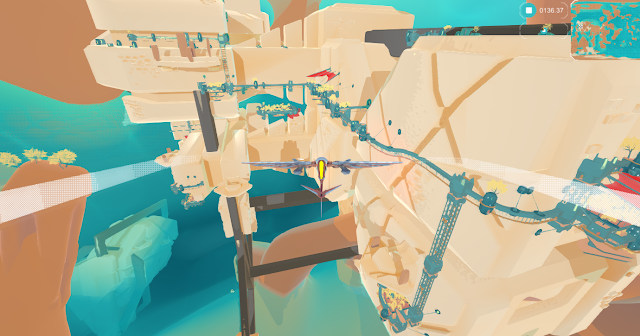

I have a soft spot for games which make the act of moving engaging: any game in which forward momentum is more interesting than holding the control stick up, whether it’s ziplining and parachuting in Just Cause or chaining grinds in Jet Set Radio. Inner Space, a zen flight game developed by PolyKnight Games aims to do just that, letting players glide and dive freely through surreal environments in order to unravel the details of a world-ending calamity. It’s a game bathed in comforting block colours featuring vast, non-threatening environments as playgrounds for its precise six-degrees-of-freedom flight.

PolyKnight Games cite other relaxing exploration games like Proteus and Journey as its key influences, and the similarities are apparent from the very beginning. Inner Space moves at a peaceful, meandering pace, using movement to keep the player engaged while creating a slightly mysterious main story arc to maintain interest. The biggest draw for me in this game is the location design. The game is set in the insides of a hollow planet after an enormous calamity – you play as a Cartographer: a winged craft designed to fly through the world and collect relics of a previous civilisation to deliver to an Archaeologist. The gameplay is simple but effective, and I definitely found my mood lifted whenever I sat down to play.

This is a decidedly more linear game than either Proteus or Journey, as its progression involves finding artefacts which power portals to its various levels. This design comes with the inherent difficulties of systemising exploration. Games which let the player figure out where they need to go are few and far between, because being lost isn’t conventionally “fun” even though finding your own direction is oftentimes more engaging than the game telling you what to do. The result is that most games develop a kind of visual signposting, never explicitly telling the player exactly where they should go but still making the correct path obvious through colours, patterns and negative space. Inner Space, on the other hand, takes a decidedly different approach in hoping the player will discover all the nooks and passageways on their own.

Inner Space does use white lines – wind and sinewy tethers – to guide players to things they can interact with, but there’s no true path to follow in any of its levels. It’s more a game about getting lost until you stumble upon the way to the next locale. Players who are more accustomed to the modern, goal orientated design will naturally find themselves confused at what to do at times – but rarely does the game pose puzzles which require careful thinking or logical deduction. This is a great opportunity for some organic, environmental storytelling: it ensures that most players won’t leave one area until they’ve seen everything twice, and it drives home the notion that they are an explorer wandering through an alien world.

Unfortunately the actual plot does not hold up as well: all the implicit stuff about the locations you explore, the adventures you have and the visual and aural experience is superb, but all the specific stuff which involves text or words tend to let the package down as soon as they appear. After collecting a relic you will need to deliver it to a character in the map, who will tell you about the object’s significance in a lengthy text sequence. I was frustrated that PolyKnight wrote all this stuff about the world and its backstory, segmenting a game precisely about exploring a world and seeing its backstory with your own eyes. It compares unfavourably to a game like Bastion, which bears a similar post-apocalyptic plot structure. Bastion’s gameplay is not about exploring the world – it’s about fighting, rebuilding and discovering, while the game’s backstory is delivered as narration to complement the gameplay. In Inner Space, exploration is everything that you do; and so being stopped while you’re exploring so the game can tell you about what you just saw is redundant design that hurts the overall theme of the game. At the very least, the text should have gone onto one of the many loading screens.

Another small complaint lies with the controls – they are precise for what the game allows you to do, but they’re not the perfect set of tools to achieve the vision that the team at PolyKnight clearly wants to convey. For the most part, Inner Space allows true six-degrees-of-freedom movement. The player can change the direction of their plane’s nose, yaw their tail left and right, rotate their plane on a horizontal axis and increase or decrease the throttle. These are all necessary techniques for navigating the game’s strange spherical landscapes, but those control schemes are all crammed onto the Switch’s two directional sticks. This leaves no buttons or thumbs left to control the camera. Subsequently, Inner Space has a permanently fixed perspective that centres on your plane’s tail, so there’s no way to properly look at something without angling your plane towards it. Now consider the fact that your plane is always moving forwards, unless you guide yourself to one of a few rest spots where you’re allowed to look at your surroundings before taking off again. In a game at least partially about looking at things, this creates a problem.

The developers evidently noticed this issue too, adding in the ability to “drift” – by holding the ZL button, players can keep their forward momentum steady while moving their plane’s head and thus their field of view, and by releasing the button they can jet forward with a burst of speed. This is the only way to move precisely enough to achieve some of the more elusive relics, and it’s a serviceable mechanic, but it’s also a bit of a copout. Constant use of drift robs the player of the kinaesthetic sensation of flight, because you’re able to make impossible turns and change directions immediately regardless of what realistic physics might say. It’s an unfortunately gamey mechanic that undermines the game’s core conceit.

The respite to all of this is the game’s underwater segments. It’s hard to explain but because you’re inside a hollow sphere and gravity comes from the edges instead of the centre, water pools itself to form a perimeter of the entire space. The player’s ship has two modes – flight and aquatic – and the latter subjects your ship to the forces of gravity. It’s a real mind-blow moment when the player first hits ZR to transform their aircraft and then falls… sideways? Try it a few more times from different angles and you’ll soon realise what makes Inner Space’s world design so remarkable. Aquatic travel also has its fair share of perks: the controls are more like Pilotwings than a proper flight simulator, and the movement speed is slowed down so players can enjoy the scenery without smashing into things. It’s a shame that the developers didn’t find more creative things for the player to do while they’re in the water however – it does tend to play second fiddle to the air segments.

The game doesn’t go to great lengths to stay varied over its playtime, and even some environments end up looking to similar to others. Aside from a cryptic grid of coloured circles on the menu screen, there are no indicators for player progress, so players had better remember which places they have and haven’t been if they want to quit and come back later. If the developers wanted to make a game about the joys of aimless flight, I would have loved to see more varied environments and a way for the player to look around as they glided. On the other hand, if Inner Space was to be a game about collecting things, it really needs better signposting, or at least a bigger radius for your Switch controllers to buzz when you’re nearing a relic.

Inner Space is not the perfect zen-game that it could have been. Despite moments of brilliance and an overall lovely aesthetic, there are mechanics which seem to be at odds with each other and thus the game seems conflicted. One moment you’re slowly following an enormous, glowing beast through an oceanic tunnel, and the next you’re chaining drifts together to zip through tight caverns while breaking through cracked glass panes. Whether you’re looking for peaceful flight or aerobatic action, Inner Space’s ideas have been better done elsewhere.

– Harvard L.

Contributor