Review by Matt S.

Beholder left me cold. Given that the intent of the game is to depict a dystopian nightmare pulled right from every image we’ve ever had of socialist eastern Europe, “leaving me cold” was probably the intention, but there are games that have done this theme better, and leaving me cold to the point that I don’t actually care what’s going on was probably not the intention.

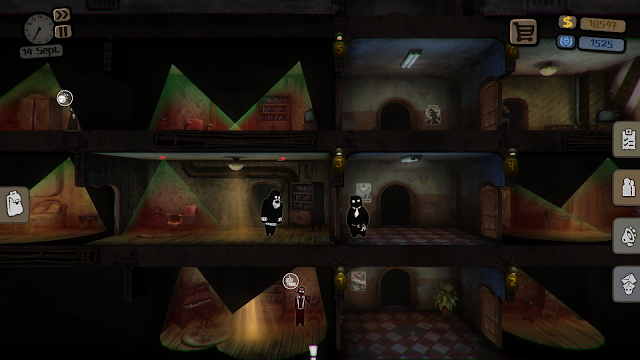

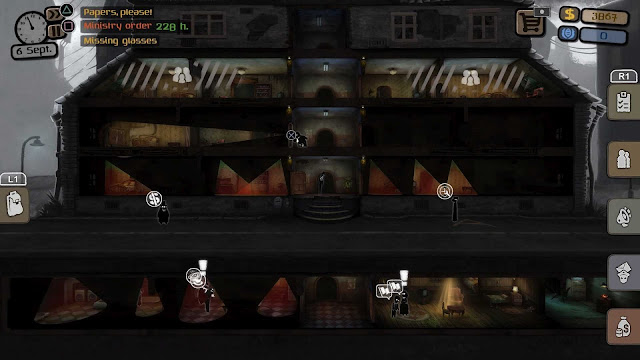

In Beholder you play as the new landlord for a state-owned apartment building, and your job is to manage the building, while also spying on the residents, installing monitoring cameras, and, when they’re not at home, rummaging through their stuff. The reason for this is that the powers that be have demanded that you keep an eye out for contraband and signs of dissidence, and report those to your superiors so that they can come and “deal with” the criminals.

Of course, what makes them criminal is often completely arbitrary and deeply unfair. As you play, the government will regularly issue new laws and regulations which you need to add to your list of things to keep an eye out for, and these can almost feel comically arbitrary at times; an ordinance banning the consumption of apples or wearing jeans for example. Another restrictions might be on the number of letter blocks that a child can own and play with. The way the game’s written is to make these ordinances darkly satirical, but it’s worth nothing that they’re not actually unrealistic. Authoritarian regimes in socialist dictatorships would indeed try and manage the frequent issues they faced with scarcity by banning or greatly restricting things that we all take for granted.

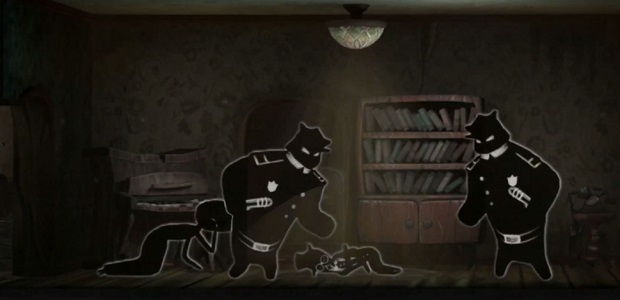

Mixed in with laws outlawing books that don’t suit the government’s rhetoric, and other similarly insidious restrictions, and you’re meant to feel pretty bad about your job in Beholder. The game adopts a grim aesthetic indeed, and it’s rare that you’ll come across a character who’s interested in perking you up. Misery is the overwhelming atmospheric tone in this game, and it’s extreme to the point of being dehumanising; indeed, all the characters are presented as blacked out silhouettes in representation of how little identity people are allowed to have in this kind of political and social environment.

There’s a downside to this approach, though. One of Beholder’s core goals is to leave you consistently conflicted by asking you to report people to the authorities that you know are innocent of any genuine wrongdoing, or even doing things you agree with. I know that if our government here in real life were to make books critical of it illegal the very last thing I’d be doing is reporting people who owned those books to the authorities. Beholder works hard to try and make it difficult for you to report people who break its government’s arbitrary laws; for example, the other tenants in the building will be friendly to you, and even give help you out. You’ll find yourself spying on a couple who just lent your wife a fry pan to cook up something tasty to make your miserable family happier.

As the story continues to play out, whispers of revolution become firmer, people take greater risks in advocating for freedom and, somehow, the apartment building you’re managing is a centrepiece to this all. There you’ll have some decisions to make about just how far you allow the flames of revolution grow, set against the pressure placed on you by the unforgiving government, and your desire to, simply, do the right thing and not have good people that you’ve come to like go to jail. Of course, all of is in turn set against the fact you’ve got a family and you’re meant to want to provide for them, and there are times where bad things happen to them, such as your little girl getting sick and having an astronomical medical bill in front of her…

Unfortunately for Beholder those efforts fall a bit flat and in the end you’ll end up reducing every decision to the gameplay benefits that you derive from it. You’ll realise that you can’t achieve everything you need to, while coming out clean, and, eventually, you’ll be making decisions on a very arbitrary basis simply because you know you need to take the narrative down a particular path to reach one of the game’s multiple endings that you hadn’t encountered yet. It crushed me to realise about midway through that I wasn’t being given the opportunity to play as “me”, and make decisions based on my own moral core, because the game is so explicitly leading in the results to each action that you might take.

You’ll be given a deadline to report suspicious activity or contraband. If you don’t so it, you’ll be punished, have less money with which to buy things, but you might end up with what you need for your family or other tenants. Going into decisions where, for the most part, you’ll know the results beforehand, and that makes the game all too easy. It’s mechanically challenging, yes, as you’re fighting a war of attrition from day one (i.e. for the most part you’re losing more than you gain), and time management when you’ve got competing demands can become truly stressful. But not challenging in a way that a game about making decisions should be. Sure the characters will try and convince you to take an emotive stance and there’s meant to be that element of moral conflict in doing a bad thing for a bad government in the interest of self-preservation, and there’s always the temptation to allow corruption to take over, but these characters are silhouettes and just aren’t able to convey enough emotion or personality to make you genuinely care, so you’re simply going to be motivated by which of the decisions promises the greatest gameplay-orientated rewards.

A similarly-themed game, Papers, Please, was far more effective than Beholder in creating this same aesthetic, tone, and then slipping that moral conflict into the decision making process. It was so effective because, mechanically, the game was really quite simple, and this forced you to focus on the minimalist, but incredibly well-written, character stories. It was that much harder to do something cruel to a person in Papers, Please, because the way the game was constructed made you feel like progress through the game was secondary to pondering over what you’re being asked to do. Beholder has too many gamey elements to distract you from the storytelling, and those gamey elements continually reinforce the need to put morality aside to make progress.

There are moments where the game hits hard, particularly across its multiple endings, which all tend to reinforce the grim sense that there are no winners under a totalitarian regime. Even the very best ending has a note of misery to it, referencing the scars that will remain on the country that has been under a totalitarian regime, even as things turn around. But again the game continues to undermine itself by putting the experience into such a gamey context.

As a game, Beholder is really well made. It has an interesting aesthetic, clever, challenging mechanics, and plenty of paths through the game. Its real struggle is in getting you to genuinely care about what’s going on, and it’s hard to get there; the gameplay too often makes it too clear that you need to make decisions that have little to do with your moral core.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

|

| Please Support Me On Patreon!

|