Review by Matt S.

At the end of the Middle Ages, leprosy disappeared from the Western world. In the margins of the community, at the gates of cities, there stretched wastelands which sickness had ceased to haunt but had left sterile and long uninhabitable.

– Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization

One of the central arguments put forward by Michel Foucault, one of the pre-eminent philosophers of the modern era, is that “madness”, as society now conceives it, is something to fear, and lock away, more as a way of defining society itself, than a reflection on the insane needing to be silenced. Long ago, people would ostracise lepers; forcing them into communities separate from the rest of society, and in that way community was built behind the idea that “normal” was defined as being a “not-leper.” Once leprosy declined in frequency and nearly disappeared, society needed a collective “other” to separate from the rest of it, in order to, again, define normalcy. Society found that in “the insane.” Being “insane” (often based on arbitrary definitions) became a pejorative. Those who were determined to be sufficiently different from the “normal” as to be considered “insane” started to be confined to mental asylums, studied, and medical professionals started to try and “correct” them. Because in being “not-normal” they must, by definition, be “wrong.”

This goes on to this day, and, historically, games have been very complicit in the social drivers maintaining this pejorative othering of the “insane.” If there’s an “insane” character in a game, from Kefka to the various villains in almost every horror game ever designed (hello, Outlast), then the mental illness is generally a source of evil; the character is evil because he or she is insane. Even when the “insane” character is not outright evil – such as in American McGee’s Alice – her mental condition is still presented as a problem; her insanity preventing her from being who she should be, and that she’s a lesser person for it.

This is one incredible combat system too. #PS4share https://t.co/8saFt35G3E pic.twitter.com/UDBB6vLaIG— Matt @ DDNet (@DigitallyDownld) August 9, 2017

Hellblade’s Senua is one of the first characters we’ve seen who has a mental illness or condition, but is not treated as an object of pity and/or fear. The development team at Ninja Theory have always had a penchant for crafting characters and games that really push the envelope in terms of taking characters and building stories that really encourage the player to sympathise with them. For example, the team’s take on the classic story of Journey to the West in Enslaved did a better job of representing that character as an emotional being than we’ve seen in any film I can recall (and that’s not to even mention the ridiculous – but admittedly fun – Monkey TV show from a few decades ago).

Hellblade was developed with close collaboration with experts in mental health, we’re told, and I completely believe it. Senua has voices in her head talking to her, and she clearly struggles with the emotional weight of her quest, but this condition doesn’t inhibit her. Nor does it make her dangerous to others – or herself. In fact, the voices guide and support her through the quest, reflecting – as they do in real life – that in many cases, people with these conditions have them as a coping mechanism to help them understand and function within the world. I certainly came to appreciate the voices – the number of times they saved Senua’s back by warning her that an enemy was right behind her was enough to be grateful for them, let alone the way they helped guide me through puzzles.

In fact, the game itself does want you to tune in to those voices. Through the many puzzles and combat situations, ignoring them will make navigation and survival almost impossible. There’s so much illusion and trickery that goes on in Hellblade that the warnings and advice imparted by the voices – while not always reliable themselves – are an important resource for making sense of it all. I’m not going to give anything away, but where you find yourself stuck – and the occasional puzzle is tricky enough to be confounding – chances are you’ve forgotten to listen to the ever-present voices. If Senua has to exist with their conversations drowning out her own thoughts, then so should you.

The game itself is an incredibly grim, dark descent into a literal hell, as Senua first arrives at the bridge to hell, and then works to open her way across it before crossing it in a bid to track down a dead loved one, whose head she carries on her belt. Her intention is to save him, though from the outset we’re led to believe that that is a futile quest, and Hellblade has a nihilistic outlook on life and death that is as intense as I’ve ever seen in a game before. It’s utterly beautiful in its complete darkness, but this is a game I couldn’t play for long periods of time without needing a break; not because it was particularly frightening, gory, or disturbing, but simply because its unrelenting intensity and extreme bleakness would build up to a kind of claustrophobia; I needed to put the controller down and get a bit of air. I don’t write that as a criticism, however; the game was affecting me so deeply because I was so completely drawn to it and involved in Senua’s quest. That’s rare, and that’s quite special.

Indeed, taken as a metaphor for the way people with mental illness often struggle with their own personal journeys through life (and Hellblade is clearly that), the heavy weight of the darkness in the bleak world that Senua navigates is appropriate, and important. This is not a game that’s particularly “fun” to play, by conventional standards. There aren’t moments of levity, as we have in most action adventure games. There are loot and experience levels that help to make otherwise dark games like Dark Souls addictive and “gamey.” There aren’t open worlds, side quests, and the like, either. Heck, the game outright warns you that it’s willing to delete your save and make you start from the start again. As most people now know thanks to spoilers in other media outlets, there’s more to that statement than seems on the surface, but the point is that the development team clearly didn’t want you to have “fun” with Hellblade, so much as absorb its message and empathise with Senua and her circumstances.

It’s a risky game, in other words, and though Ninja Theory is no stranger to taking creative risks that lead to poor sales (actually, I just described almost every one of its games), Hellblade is at another level entirely. People are going to walk away from this one feeling reflective and mellowed, rather than celebrating its combat, difficulty or mechanics. Or they’re going to walk away wishing they spent their money on whatever generic “fun” shooter was released this week instead. What will trick players is that on some levels Hellblade appears to be something that it’s not. There are superficial resemblances to the Dark Souls series, for example, in the flow of combat, and Hellblade knows how to be difficult, but the combat is also nowhere near as intricate as in the Souls games. In terms of exploration, rather than being open, Hellblade features any number of no going back moments. Senua will jump down from a ledge to explore a new area, and she won’t be able to climb back up again; the only way to approach this game is by moving forward.

Every bit of the game’s design has some kind of symbolic purpose; in combat Senua is battling her own demons as much as physical threats, and Ninja Theory wants you focused on the extreme impact and visceral nature of this, rather than worrying about weapon combinations or attack patterns. Preventing players from leaving areas they’ve jumped into is symbolic of Senua being unable to escape from herself. Time and time again Ninja Theory demonstrates that it’s willing to sacrifice “fun” to further the narrative strength of Hellblade, and I love the company for that.

There are some concessions to the modern player. A generous checkpointing system prevents players getting frustrated if Senua should “die,” though surely there would have been thematic value in forcing players to retread vast distances. The team’s also recognised the value of presentation, and Hellblade looks as good as any blockbuster title out there. There’s even a photo mode, as immersion-breaking as it is, and it’s the best photo toolset I’ve seen this side of Horizon.

I struggle to describe just how much of an impact Hellblade has had on me. It’s a powerful piece of art, and it has been masterfully executed by one of the most under appreciated and creative game developers out there. The development team knew it had a potent story to tell, and has done everything in its power to make Senua not just another character in another game to pass some time with, pressing buttons and having fun. Ninja Theory had loftier ambitions than “fun” with Hellblade, and even though the game could have failed over, and over again in reaching for that ambition, it never falters. Never.

As a big fan of Ninja Theory and what it stands for, I was already looking forward to Hellblade, from when I first saw it in action a few years ago. My expectations have never been so thoroughly exceeded. As I said, I have a great deal of difficulty putting in words just how much I love Hellblade. It’s just that powerful.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

|

| Please Support Me On Patreon!

|

hi

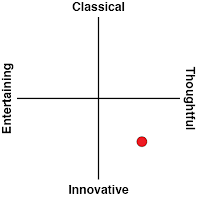

whats your Factors in deciding whether a game is classic or innovative or thoughtful, …