Review by Matt S.

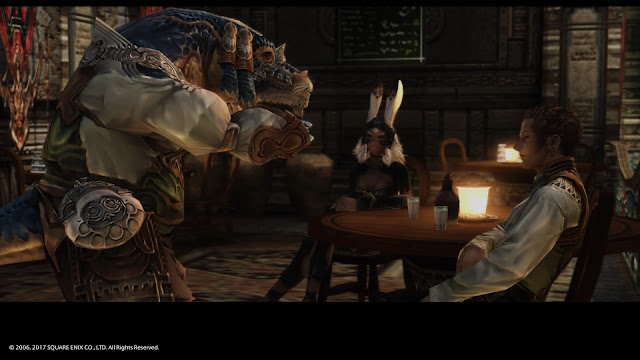

For quite some time Final Fantasy XII has been the only game in Square Enix’s most venerated franchise that hasn’t been available on a console being sold on the current market. That has now been remedied, and I couldn’t be happier.

I know I’m an outlier when I say that this is my favourite Final Fantasy of the entire series. It is however the truth, and as Final Fantasy was the JRPG franchise that I grew up with, for it to be my favourite is saying a lot. The game offers an intriguing and detailed setting and lore, which I found immediately appealing when I first played it, and that persists to this day. Where most Final Fantasy games feel like the entire universe centres on the heroes and what they get up to, in Final Fantasy XII there’s a sense that the characters are simply players in something far larger than any single one of them. There’s a richer sense of history and culture to Final Fantasy XII, perhaps because it’s set in Ivalice, which also plays host to the Final Fantasy Tactics games, and having a setting across multiple games helps to build out the setting itself into a kind of character. Beyond whatever commercial success this game might have, I dearly hope Square Enix does look to create more games in the world of Ivalice, because it’s one that clearly has many more stories to tell.

Beyond the setting, what is most appealing about Final Fantasy XII is that it is one of the franchise’s most complex in terms of its narrative. Most Final Fantasy games before Final Fantasy XII are really quite cut-and-dry stories about good in opposition to evil. At times that theme forms the core hook around the entire narrative, such as Cecil’s rebellion against his king-turned-monster and redemption (complete with the distinctly unsubtle conversion from dark knight into white-clad paladin). At other times the opposition to evil is simply a hook to drive players onwards into the next conflict, but in each and every Final Fantasy game, prior to XII, the bad guys are bad, the good guys are the protagonists, and you’re never meant to question any of that.

Final Fantasy XII, however, adopts a more relativist approach. The core narrative spins around a war and conquest, where a mighty empire has dominated a small and feeble nation, and you play as a resistance faction within the losing side, seeking to expel the invaders. Where Final Fantasy XII succeeds as a modern example of storytelling, and allows the game to feel current and relevant over a decade after it was first released, is in the way it questions assumptions that we might have about the moral centre of the empire and people within it, as well as the activities that our “heroes” get up to.

The empire, despite being the aggressor, is, for the most part, portrayed as a civil nation. It’s democratic, and takes pains to work towards peace and unity in its captured territories (rather than subjugation). Further, without giving the plot away for people who haven’t yet played the game, it includes numerous officials in high up places that are very decent people, or at least motivated by a desire to, essentially, do the right thing. The most intimidating “enemies” that you’ll fight are the judges; symbols of law and order that were always going to appear threatening to those seeking to foster anarchy, but we’ve only really got the word of those same people to tell us that these judges are a force of evil in the world. Those people would include your party of heroes in this game.

Meanwhile, the actions of the protagonists in Final Fantasy XII are highly suspect at times – and indeed half the group are either pirates or aspiring pirates. The nation they seek to restore was a monarchy which was guided by higher powers from a spiritual realm (gods by another name) who are quite willing to order their people commit genocide when it suits their purpose. Luckily, the protagonists are also presented as determined, not immoral, so they won’t go as far as genocide, and you’re don’t end up playing anti-heroes so much as one group of people with a vision, ideology and goals that’s in conflict with the other group of people. Cue relativism.

Throw in some thinly-veiled metaphors for much of the conflict being over access to the resources that make weaponry of a similar power to nuclear arms, and the fact that the protagonists hail from a nation that, through its architecture and fashion, looks reminiscent of a 1001 Arabian Nights-like Middle East, and you’ve got an allegory for the real world that is somehow more poignant now than it was back when the game was originally released. All of this comes with a consequence; because Final Fantasy XII needs to spend so much time building perspectives and establishing a believable world in order for its political message to come through, the party of heroes themselves don’t feel as fleshed out as in other Final Fantasy games.

The immediate predecessor to Final Fantasy XII, Final Fantasy X (remembering that XI was an MMO), had a cut-and-dry story of heroism against villainy, but through that was able to develop the personal relationships between the characters, particularly the romance between Tidus and Yuna. They’re not the only ones, either. Thin Rosa and Cecil in Final Fantasy IV, Rinoa and Squall in VIII, and so on and so forth. Generally Final Fantasy has worked in connecting characters with players through their emotional connections to one another that is presented in a way that is easy to relate to, and subsequently draws us into the world and the characters through those connections. In Final Fantasy XII the relationships between the characters is less of a focus, because the game’s really about how those characters relate to the world around them. It can come across as academic; characters designed to support the theme, rather than engage the player as “people”, and aside from the Han Solo-like Balthier, few people list Final Fantasy XII characters as “favourites” for this reason; they’re simply harder to relate to.

Not to me, though. Princess Ashe has got to be my favourite character in all of Final Fantasy. Before Lightning from Final Fantasy XIII showed the world that Square Enix was moving its female characters beyond mages that could never handle the physical work of the males in the front rows of the fighting, thieves that were good for getting a bit of loot but not much more, or damsels in distress, Ashe was there as an incredible empowered, determined, and strong warrior, both in terms of narrative and the way she was designed to be used on the battlefield.

In the HD remaster of Final Fantasy XII, you have a great deal more control over how characters develop than in the predecessor, so if you do want to make Ashe a meek white mage (why would you?), or give the job of using guns from Balthier to another character, you can do that. In the remaster there are a dozen jobs that you can freely assign to each character, and each character starts with one job, though will eventually acquire a second. Each job naturally has a different role on the battlefield, from the high-evasion melee combat monks to the heavily armoured knights, the various kinds of magic users that will be familiar to Final Fantasy veterans (white mage, black mage, battle mage, time mage, etc), and archers and gunslingers. In combat you can only have three heroes at a time, however, so the trick is to build that mix of three (later, six) sets of jobs that work together well to counter the varied combat challenges that enemies will throw at you.

When it was first released, Final Fantasy XII’s MMO-like combat system put a number of people off, but I think in the context of how the JRPG genre has since developed, players will be more comfortable with it now, as it’s something we see far more frequently. For the first time in a single player Final Fantasy (again, discounting Final Fantasy XI), Final Fantasy XII removed random battles from the game, instead placing enemies directly in the overworld. In that game, as with the remaster, when combat is joined, little lines pop up from each combatant to show who it was targeting. You’re in direct control of only one of the three heroes in the active party, but you can also issue commands to either of the other two. Alternatively, you can set each character up with gambits – a series of command switches, that allows them to operate some pretty complex command flows.

So for example you might set a character up to prioritise healing any character under 50 per cent health. If all characters are above 50 per cent heath, the next “move” might be to cast fire on any enemy vulnerable to fire. If there are none of those enemies, and third command might be to cast slow on the enemy with the highest health, and if the enemy with the highest health is already slowed the fourth command might be to start using melee attacks on whatever enemy the party leader (the one you have direct control of) is targeting.

At first characters will only have access to two commands under this gambit system, but it quickly expands out as they level up. You’ll need it, too, with many of the boss battles all but requiring that you have your gambits finely tunes to take advantage of enemy weaknesses while compensating for your party’s own. As a bonus, the remaster of Final Fantasy XII also includes a “trials” mode, which lets players test their skills against ever more difficult enemies, and in here unless you’ve properly configured your gambits and, at times, thought very creatively about them from the millions of total possible combinations, you’ll be toast.

Outside of combat, the world of Final Fantasy XII is impressively large in scope, and a real joy to explore, not least because it is so pretty. The developers had a stunning base art direction to work with when it came to rendering the game in HD, and they’ve utterly succeeded – though the game doesn’t look to the standards of Final Fantasy XV, of course, it’s still very much feels like a modern game – particularly with the architecture and environments, which are vivid and beautiful. Character models look great – particularly Ashe, though I might be biased – but with a couple of them (Penello, particularly) there’s an grimy texture over the faces, which looks odd, though it’s only really noticeable in cut scenes.

The game’s also supported by the most wonderful, unique musical vision for the Final Fantasy series. XII is the only numbered Final Fantasy that Hitoshi Sakimoto led the scoring on. This was something of a blasphemy for many of the long-term Final Fantasy fans, as it was also the first numbered single player Final Fantasy that Nobuo Uematsu did not lead, having recently left Square Enix before development on this game commenced. Years on I would hope people look at the score a little more soberly, and it really is a masterful work that subtly builds in traditional Final Fantasy motifs with its own identity. Now fully orchestrated for the remaster, it’s the perfect accompaniment that really helps to set the scene.

Final Fantasy XII was a commercial and critical success when it first landed, but it proved polarising with fans, and has spent most of the time since being buried down the bottom of the Officially Approved Ranking List Of Final Fantasy Games By Real Fans (™). Us “casuals” that dared enjoy it have spent the last decade or so being told we’re wrong for wanting a HD remaster. But we have it now, and I do hope that Final Fantasy XII will be re-assessed under different expectations to what were placed on is as a follow on from the hyper-traditional Final Fantasy X. Final Fantasy XII’s willingness to be different and innovative has left it feeling every bit as modern and poignant now as any new JRPG on the market, and it remains my favourite game within a series that I hold very precious to me.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld

|

| Please Support Me On Patreon!

|