Review by Britta S.

The first thing the Finch family starts building in 1937, when they are shipwrecked on Orcas Island, on the Pacific Northwest coast, is a cemetery; only then do survivors Sven and Edie, with their little daughter Molly, begin the construction of the Finch home. This is how the individual stories will play out, each one of the Finch lives through the generations: it always starts with a death. Indeed, their deaths are the only part of their lives we get to experience in scripted gameplay; the rest you have to piece together by immersing yourself in the details of the Finch home. And what a home it is, and what a cornucopia of detail we get to see and almost absorb as if by osmosis.

Related reading: Another “walking simulator” that explores similarly potent themes is Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. Matt’s review.

You first come upon the Finch place as young Edith Finch (born 1999) who takes the ferry to Orcas Island to revisit her old home. She is now the last surviving Finch and this is her inheritance. You walk through the woods; the tall trees sway, their gnarly branches creak, and the wind soughs through them unendingly. I can’t think of another first-person game where I was so quickly, so completely enveloped by the atmosphere. I thought I could smell the dank forest odour, and my footsteps sounded eerily real. Then you see the house and it’s like a conglomeration of all the ramshackle houses you’ve ever seen or had appear in your dreams. This house has taken a weathering over the decades, but where some parts look shuttered and desolate, others have defiantly sprouted at vertiginous angles and heights. The front door is locked and you are forced to crawl through the garage side door’s doggie door panel. This is how the narrative will play out: you need to find the secret entrances to explore the rooms in this house, for all main bedroom doors have been hermetically sealed off by Edie after the occupant’s death.

I had blithely assumed that once inside, I’d be able to choose which room, and by extension life and death, I could visit – similar to Gone Home, another recent game set in the Pacific Northwest, with a young woman returning to her family home to piece together what happened by delving into the past. But this is not the case. Progress is entirely linear and prescribed, along the family tree; by opening up the first secret entrance to Molly’s room and playing through her last moments, in her imagination, you gain access to the next room and story. I hesitate to call them ‘stories’, though; they’re more like vignettes, some extremely brief, others involving more extended player interaction, but each one homing in on one, and only one defining characteristic. It’s something families do, where you know each other so well, yet choose to distill a personality down to a single puzzle piece, then embroider it through countless repetitions, until you arrive at the family myth. The Finches are no different in this respect, except that their understanding of their fate revolves uniquely, obsessively, around a family curse they brought with them all the way from Norway. The Finches simply fulfill their destiny faithfully by so many of them dying early or unusual deaths. By unusual I don’t mean necessarily outlandish, rather that these deaths are often the stuff of very ordinary mishaps or accidents, yet your experience of their deaths is anything but ordinary.

It’s the way we are plunged into what happens to those thirteen family members that makes their deaths extraordinary. I need to step back to the beginning, and to basics, to make clear what is so different, refreshing and constantly surprising about the game’s approach. On the ferry, in order to ‘start’ the game, we are introduced without overt guidance to the basic mechanics: you simulate tactile actions by pressing the right shoulder button to take a book’s top corner between thumb and index finger, then push the left stick in the direction you wish to turn the page. It feels natural and intuitive, and paring back the control scheme to essentials lifts the immediacy of the play experience into the realm of ordinary life. The other strangely natural experience is exploring the house, for this is truly a house that has been lived in, where the stuff of living is spilling over everywhere. The house contents have been left in the process of being packed up, piled up or scattered everywhere. The scenes impart a sense of a place exposed and therefore vulnerable, like a half-undressed grandmother. It’s often awkward navigating around since many rooms are small, cluttered and shaped with odd nooks and crannies. I proceeded very slowly and carefully, yet found on a second playthrough that I had missed details in plain sight.

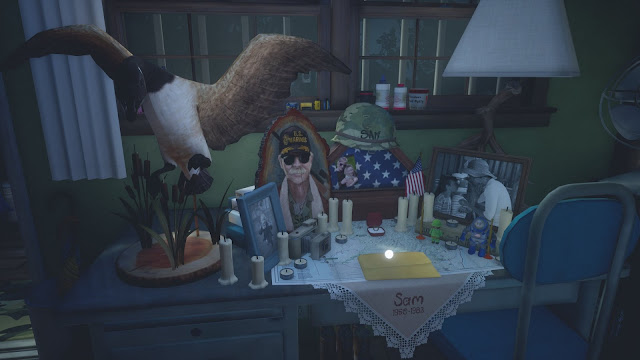

The sheer depth and beauty of the detail in every square inch is at times overwhelming. This is where the lives of all the Finches are embedded: in their books (oh, so many books! I spent so much time reading the titles!), their furniture, their knick knacks, the very fabric of the house itself. It is in each room that you will ‘see’ the character in their ordinariness, while their flamboyant death experiences transport you to the realm of fantasy, where family myths and legends are played out. The imagination soars, buoyed by certain recurring images that tie it back to the natural world of Orcas Island and personal Finch memorabilia. I was reminded more than anything of the way magical realism works in fiction (authors Gabriel García Márquez and Isabel Allende spring to mind) or in a movie like Tim Burton’s Big Fish.

What is so exhilarating, driving you on to discover each individual’s little shrine with the glowing book icon (what a delicious irony to use this to lead you into a completely interactive rollercoaster), is the boggling range of creative ideas for immersing you in the last moments of every Finch on the family tree. One moment you’re stepping into the pages of a 1960s schlock horror comic book to play out a nail biting event, the next you’re flying a kite, reeling in sentences from the sky that reveal your boyish anguish and anger. Indeed, the way text is used in Edith Finch is a delight. We find sentences wrapped organically around gates or chairs, only to dissipate or scramble as you walk through them. Words are part of the environment; words are inviting gateways into a fabulous world. We only get to read the first sentence in a shrine’s diary, then we are instantly transported into the consciousness of that Finch moment in life – and death.

I have to admit that I wasn’t reeled in by the Finch magic right from the beginning; it took a while for me to feel the rhythm of the game and be ready to embrace the joy of letting myself be submerged, even overcome, by what is a Babette’s Feast for the senses. After all, you are joyfully tumbling into someone’s death moment, spurring on the action you know will relentlessly lead to their demise. Feelings of guilt and complicity arise, interrupted by cries of amazement at how cleverly the scene plays out, all achieved with those very simple controls. One death in particular winded me, like a punch to the solar plexus, and I had to lay down my controller and calm myself. I wouldn’t say I ever felt particularly close to any of the Finches, not in the way that you get to know, for example, the main characters in Gone Home, but I don’t think that is the intention of the game.

In Edith Finch, your journey is literally along a family tree, step by step; this scaffold was never meant to be ‘gamey’, choose-your-path. You realise early on that each death will play out as it must, and that you will at the end of the journey find out Edith’s true motive for returning to the home that has grown, exactly like the family tree, into an organic presence. The true game playing resides within the death sequences; at the moment of death, this game comes alive and you grasp, you can see, feel and almost taste, that it is in this realm of unfettered imagination that the essence of gaming is at home. That is the true nature of the Finch home.

It is for the end of the journey that the developers have reserved the biggest emotional punch, an unabashed grab for your sentiment that left me teary-eyed yet also with the uneasy sense of a stumble right at the finish line. There was just a little bit too much explaining, stating the obvious; I would’ve preferred a subtler approach that leaves me to ponder the significance of events for myself. Rather like the masterful storytelling approach for the homeschooling that generations of Finch children received. Homeschooling is never mentioned, not once, in the game; it never appears on the canvas of individual death scenes. You extract this nugget by reading the spines of books, by closely examining the children’s bedrooms, and eventually you come across the space used as a classroom. This is a silent yet potent facet of the essence of the Finch family. These children grew up in a stunningly beautiful, bountiful natural world, fostered by loving parents and nourished by matriarch Edie’s extravagant and foreboding tales of a dragon and a curse. They develop a strong desire for exploring and a radiant imagination. It is surely not so surprising that they are more likely to fall prey to one exploration gone too far. The curse is a double-edged sword, for the imagination brings both joy and sadness to their lives.

What Remains of Edith Finch still has the traditional scaffold of a fixed narrative. The player cannot influence either the individual arcs nor indeed the ending: in that sense, it plays out like a book or a film. But a scaffold is just a device to allow what really matters to spread its wings, to take you deep into that other realm, where the imagination and gameplay come together. What Edith Finch has achieved on a whole new level is an overarching brilliance and consistency of both theme and gameplay, in how the two seamlessly intertwine and feed off each other. I strongly expect that this game will be used for years to come as a ‘textbook’ case to educate developers about how to compose a story by not resorting to screeds of text or long loops of audio (in the form of simulated manuscripts, letters, voice recordings etc.); almost tauntingly, in one story, the letter-being-read crutch is used, but subverted ingeniously through the gameplay. It’s the old adage: Show Not Tell, and Giant Sparrow is demonstrating how to “show” with the storyteller’s intuitive and assured confidence, while revelling in the glorious fantasy world their characters inhabit. Take our hand, they say, come with us unto these magical shores, and we will show you the pain and the ecstasy of the Finch family.

– Britta S.

Contributor