Review by Nick Hu.

If the much-awaited resurgence of adventure games is something you’ve been holding your breath for, you’d best embrace your inner Threepwood, as Thimbleweed Park is not the herald of that day. While there’s been a huge amount of anticipation for this game, spilling out of the chewy caramel brain centres belonging to the creators of some of the best adventure games that ever were, it falls short of holding par with its forebears.

From the game’s opening moments, it immediately slots into an unnoticed void in the gaming landscape, at least for those who grew up with graphic click-a-renos. Independents might still throw into the pool of adventure, and there have been reworked and remastered classics that have splashed around the edges, but nothing quite like this. Thimbleweed Park immediately bridges the gulf between the player and the game, in a way that’s very familiar.

While there was often a difference in tone around the story of most games, they were a peculiar beast, in that they always seemed aware of what they were. Adventure games would often saunter back and forth through the fourth wall, calling attention to their idiosyncrasies, stating the awareness of them being a game, and often edging toward the self-indulgent. They tended to be masters of their source genre, embracing the tropes in ways that showed vast understanding.

Not all adventures went this way, but the very many loved classics – whether you fell into the Lucasfilm camp, quested through the Sierra catagloue, or tried to stay adventure-agnostic – often paired this irreverence to the puzzles and writing.

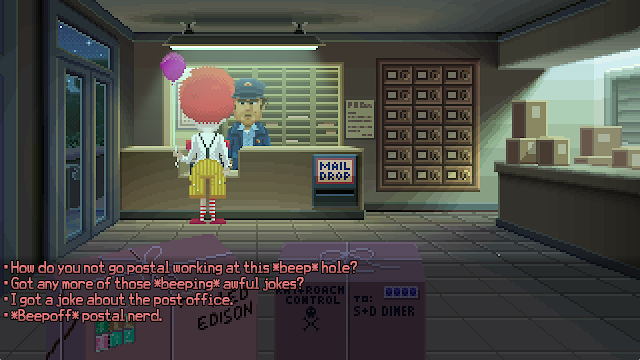

There’s five (and a bit) playable characters, and a whole load of supporting characters, such as the town’s Sheriff, a hotel clerk, and a coroner. All of them are voiced, and it’s great to hear every line in the game spoken. Ransome’s a show-stealer by far, though all of the mains really hold their own (though if Dolores never spoke spanish at all, it wouldn’t be a loss).

The characters in Thimbleweed Park all carry that sense of caricature that adventure games gravitate toward, which they especially did in the early days. They’re empty vessels that could be summed in two words – a Rude Clown, or a Game Developer – and those are main characters. They aren’t there to provide depth or grounding, but to move the plot, or provide the set-up. There are still intricacies in the game, but they revolve around the beats of the plot and the solutions to the puzzles, and are never about the characters.

That isn’t to downplay the presence that the characters provide – they reinforce that Thimbleweed Park is an adventure game – and that part of your entertainment is going to come from the humour. It’s not TV humour, like that sitcom Maniac Mansion, but unmistakably game humour, like that game Maniac Mansion. There are some great lines very early on, good enough to grab you and shout “Hey, this is an adventure game! Remember those? This is one! YES REALLY!!” The early moments really do sell the game well, and hit that perfect mix between nostalgia and something fresh.

Thimbleweed Park could have been a product of the late 80s – it uses an interface reminiscent of a slightly-better SCUMM system, feeling most similar to its form in the second iteration of Lucasarts games, as opposed to the slightly earlier ones that carried the Lucasfilm branding – but beyond that step ahead, it fits. There’s a few jokes that only work because of the perspective living in 2017 grants us, but many of them are timeless. There’s a kid in the hotel you’ll chat with, and it’s like a high-grade injection of nostalgia, because he’s expertly lifted out of that era in planted into the games. Tonally it’s Zak over DoTT, Monkey Island over Sam and Max, and without question, Lucas over Sierra.

It presents in the same style, and while it’s definitely a better looking game than its predecessors, it still hones in to that specific Lucasarts feel. The way perspective is used, the way scenes are framed to pad out content and make everything meaningful, make it a nice game to explore. There’s also a huge amount of crowd-sourced material in the game, so if you want to distract yourself by reading page upon page of contextual concept books, have at it.

Some of the pre-release hype around the game has been ridiculous, mind you. Thimbleweed Park has been long anticipated, but calling it open world? Let’s not. Claims that the game has more than you can click on in a play-through? Now you’re just being a *BEEP*. That’s not the developers saying these things. It’s a long-ish game, sure, though it never feels it.

The game has a series of parts that split up the plot, each part being of various lengths. In terms of pacing, there’s more or less four acts, though, this is made up by varying numbers of parts. The plot does zig and zag a few times, and the murder investigation that provides the initial setup is merely the first angle.

The puzzles are fairly straightforward, with the exception of the very final puzzle that involves the corpse, but the game gives you the right kind of hint. There are two difficulties in the game, and in playing the Normal mode (rather than casual), only once ran into an issue I needed a hint with – which came down to not realising an object was one I could pick up. (Adventure Game Rule #1: Pick Up Everything). Other times when I ran into trouble, it’s because I hadn’t worked out that something could be interacted with, but eventually solved them on my own. Those solves provide the other lure – a feeling of accomplishment for working out that film goes in a camera.

For all its qualities, and they are plenty, there are two major issues with Thimbleweed Park that rob it of the sheen that it should otherwise possess. The ending, and a lack of restraint.

On the ending, I feel like we’ve been here before. I don’t want to retread all of the disappointing endings that games have offered over the years, and definitely don’t want to add to the hivemind tanty that’s perpetually going on in video games in general, but the ending of Monkey Island 2 was a pretty notable one for controversy, particular in a time before the internet’s current brand of discourse.

The ending of Thimbleweed Park is extremely self-indulgent, and unsatisfying. It makes you appreciate the succinct way in which Monkey Island 2 closed, because while it didn’t offer a resolution, it left you with talking points. Game developers themselves are the ones most likely to get a kick out of the ending, and no, I’m not going to spoil it, but it didn’t provide the whammy that the rest of the game had been leading up to. The most disappointing aspect of this is that the rest of the game shows the developers at Terrible Toybox are at the top of their game, and it could have been so very different.

That’s part of the restraint issue, but the other part is the Sierra jokes. They’re in the game very early on, but they pummel the point extremely hard. Obviously most of us aren’t aware of what went on between Lucasarts and Sierra, but unless I’m missing the tone, it feels like there are still heavy grudges – at least one way. Show us on the Ransome Doll where Ken and Robert touched you, devs! It’s a shame, because while they both had their problems (though sure, monkey wrench vs random death for no reason isn’t even), all of them were loved by many. It isn’t the first time that the Sierra approach has been poked at by some of those involved with Thimbleweed Park, but The Secret of Monkey Island did it better, and without the shades of malice that seem present here.

Ultimately, this is a game anyone that loved adventure games will enjoy, and find entertainment in. There are quite a few nods to the Lucasarts/Lucasfilm stable, cameos and a continuation of jokes that have been there since the first Edison encounter. In terms of where it would sit alongside the earlier adventure games, it’s definitely a B-side, but being a B-side to the likes of Monkey Island, Zak McKracken and Day of the Tentacle is still a pretty mean feat.

– Nick Hu.

Contributor