Review by Matt S.

To be honest, there’s not much more I can say about the games Danganronpa 1 and 2 that I haven’t already covered in my reviews. They’re visual novels, and I find them to be utterly brilliant. Bringing the two games together into a single package on PlayStation 4 is a superb thing for Spike Chunsoft and NISA to do. With Danganronpa 3 around the corner for the PS4, the many people out there who don’t have a PlayStation Vita now have a chance to catch up before immersing themselves in what promises to be a very special game later this year.

It’s something a certain publisher (yes, Square Enix) should have thought of doing with NieR and Drakengard before throwing players into the deep end with NieR: Automata.

But I digress. The point is that this package of two brilliant games offers superb raw value. Each Danganronpa title is a dozen hours or longer in length, depending on how fast you read through it. While there’s a tiny bit of fuzziness in the art as a consequence of upscaling everything from the tiny Vita screen to the big television set, the actual art direction remains vibrant and utterly stunning in its imagination. One of the strengths of the Danganronpa series is its characters, and everyone (and I mean everyone) ends up with their favourites from the eclectic bunches in both games, in part because their visual design is so strong.

So, on a purely technical level, the games are executed close enough to perfect that the original ratings I gave the games don’t need to be changed. In other words, you’re getting two legitimate five-star games (and games that have won DDNet GOTY awards) in one. How awesome is that? Have a read of those two reviews (which are spoiler-free), and you’ll know exactly why you need to play these games, if you haven’t already.

For the rest of the review I’d like to explore one of the game’s core themes which I haven’t explored previously; to show that, the more you dig into the Danganronpa narrative, the more insight it returns, and that every player will take away something different from it – just like with any great work of art, really.

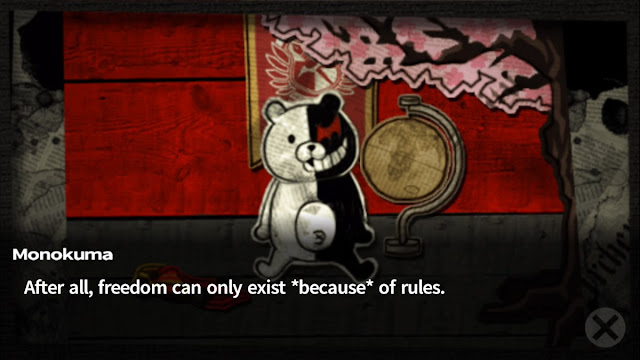

This time around I’d like to take a Marxist reading of the games, because both Danganronpa titles assuredly have a lot to say from that point of view – to the point where they can be “read” as communist works actively arguing against the neo-conservative and libertarian systems that power most of the world today (the real communism, folks, not the evil bogeyman that McCarthy fake-newsed into the world back in the 50s). Oddly enough, the figures of Monokuma, the antagonist of Danganronpa, and Willy Wonka, from Dahl’s novel and the films, are similar in thematic principle in this regard.

For those who haven’t played the Danganronpa games before, here’s a quick, spoiler-free summary: A group of school kids, each representing an ‘ultimate’ trait (ultimate athlete, ultimate writer, ultimate lucky guy), have been kidnapped by a puppetmaster, represented by the black-and-white (literally) bear, Monokuma. This “Monokuma” traps the students in a space (a school for the first game, a tropical paradise for the second) and sets them a game: they can either live in these prisons indefinitely, or one of them can kill another to be let free. The catch is that if someone does murder another person, they need to also get away with it; if the murderer is found out, that murderer is instead ‘punished’ (executed). And so start the games, with various characters succumbing to the desperation to be free and attempting to pull off the perfect murder to make good their escape.

I’ve already written about how the game plays on various social and economic theories, most notably game theory, an economic model that explains how people conflict with one another – the reasons why they do so (rather than co-operate) and the results of those conflicts.

But there’s another applicable social and economic theory that I haven’t addressed yet, and that’s the theories of Karl Marx. Marx is, of course, the fellow credited with defining communism, a concept that would subsequently become a dirty word (thanks to the vested interests of wealthy people who lose out under egalitarianism). Really, though, to greatly condense the argument: communism is not something evil – it is simply driven by the idea that the “state” and everyone within it should provide in equal measure for everyone else, and that a society is at its healthiest when the gaps between the rich and the poor are minimal or nonexistent. Any form of welfare, or any government levying taxes to provide services, is in effect communist (redistributive) principles at work. You’d have to be crazy to think that that’s not a good thing.

The opposite of communism is what libertarians and conservatives believe in: small government, low taxes, and individualism; and they believe in these things because the wealthy (i.e those very libertarians and conservatives in power) can monetarily benefit from and exploit the poor in such an environment. All the poor or middle-class Ayn Rand fans shoot themselves in the foot by supporting this kind of economic environment and voting for conservatives and libertarians. Those same policy makers ensure that education is skewed towards vocational pursuits, rather than these ideological discussions, lest the population wake up to what’s really going on and that they’re supporting the side that isn’t interested in them.

Anyhow, that background aside, Danganronpa reflects both the utopia and critical flaws of Marx’s thinking behind communism. Across both games the imprisoned students are presented with abundance and fulfilment; their every need is provided for within the school and tropical resort. We see that the food and accommodation they have access to is of a particularly high, comfortable standard. They have unlimited free time (a core tenet of communist thinking is that leisure is critical to human contentedness), and have free reign over their large, comfortable, spacious environments. The whole point of all this is that “Monokuma” provides these kids with a utopic opportunity: learn to be content with simple communal living, and live forever in comfort.

Monokuma’s true villainy is, then, that he provides the students with all the encouragement they need to throw the opportunity for a utopia into the bin. Each time, Monokuma introduces something to the students that makes them *need* to try and kill one of their classmates and escape. It might be a videotape of what’s going on with their family and friends outside their prison, for example. A more extreme example is a threat of starvation if the group can’t figure out a way of escaping from one particular enclosed area (which of course it is possible to do without killing another student, though the solution is initially unknown). The core of each of these motivations is the same though: the only motivation a person needs to try and kill another is simply to give them the opportunity to ‘get ahead’, to indulge a selfish desire at the expense of the group’s well being.

And, of course, with each and every motive a murder inevitably happens afterwards. The greatest flaw with Marx’s economic principles is to assume that people can live together for communal benefit without someone looking to take advantage of the situation. That’s a rather simplistic analysis of the problems with the communist utopia, but it’s the basic thrust of the issue. Basic human psychology simply means that humans are too competitive to let that happen, and the reason that Monokuma is so effective as a villain, as many horror villains often are (Jigsaw from saw, Freddy Krueger from Nightmare on Elm Street), is because Monokuma himself is the least threat of all. The real threat for these kids is they themselves, and Monokuma’s role is simply to give people the environmental context that will lead to mutually assured destruction.

This is just one other way to analyse the narrative of the two Danganronpa games, and as I said before – as with any great piece of writing – each person will respond to these narratives differently. What is important to any great visual novel is that it has great writing, and the Danganronpa games are by turns hilarious, reflective, intense and jovial, the characters are all unique and interesting, and the twists and turns are often startling. Visual novels just don’t get better than these.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld