Retro reflections by Matt S.

When I was a real youngster, before I had even really started playing video games (I didn’t yet have my first console – a Game Boy – and though the family had a Commodore 64, I very rarely used it), I discovered a box that my parents had stored away with the family board games with “Dungeons & Dragons” written on it. Being a great fan of King Arthur and The Hobbit (I had an advanced reading age), I was already very keen on fantasy, and the box art for this game really drew me in.

Of course, I was a little young at that point to really understand the nuances of the game. This was the original Dungeons & Dragons box, which was a simplified version of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (at that stage, in its second edition), but even still, I wasn’t quite ready to actually play the thing. One thing I do remember, however, was being absolutely enthralled with the sample dungeon that came with the game.

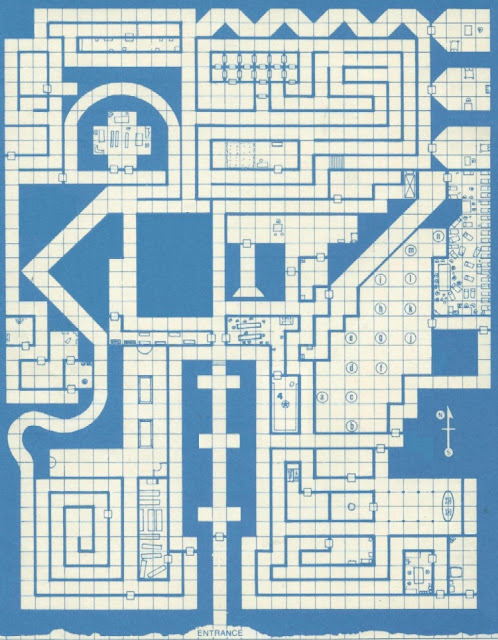

For people less familiar with tabletop RPGs: in these games, one player takes on the role of the Dungeon Master. Their job is to lead the players through their adventure by being the storytelling, and controlling the monsters that the heroes fight in battle. They are also responsible for describing the dungeons that the heroes explore. In the sample adventure module that the game came with, there was a map, laid out on grid paper, that showed the rooms, corridors, and traps that the players would face.

|

| This was the box that held the game that started my life-long obsession with RPGs and fantasy games. |

And of course the players wouldn’t have access to this map. Instead, they would need to manually create their own map as they explored, corridor by corridor, room by room. That exploration element really appealed to me as a child. The simple lines drawn onto grid paper held mysteries, danger, and exploration, and so, grid paper came to represent to me a delve into the unknown. To this day I get nostalgic when I see books of grid paper. Once I was old enough to start playing the game, I would fill books of them with my own dungeon designs, and then fill even more books in playing the game with friends.I would always insist on being the ‘map guy,’ and the people I were playing with would always be happy for me to do that. To them, mapping was a chore. To me, it was exploration itself.

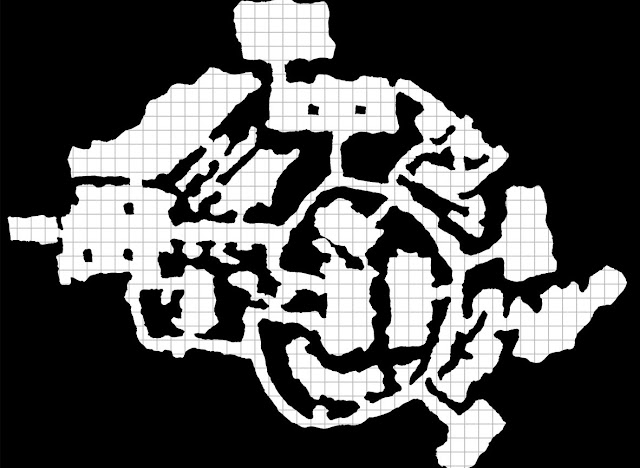

When I started playing video games, I naturally gravitated towards the RPG genre, based on my love of fantasy and Dungeons & Dragons. I got into JRPGs later on. In the early stages I was all about the Dungeons & Dragons games on PC, as well as associated games like Wizardry and Might & Magic. As I discovered to my delight, in those days, the games wouldn’t make your maps for you. You would need to have a book of grid paper, and map things along as you played. The design of these games made mapping easy; they were laid out as though on grid paper themselves, where one ‘step’ would equal a shift of one ‘square’ on the grid, which made manual mapping quite easy. The overly simple graphical representation of the dungeons, in which corridors could all look like one another, made it very easy to get lost without that precious map. And so, as I played more of these computer RPGs, I had a box that would slowly fill up with graph paper that had little doodles all over them.

This is something that I feel the modern dungeon crawler has lost. For the most part, in this genre now mapping is automatic. The notable exception is, of course, the Etrian Odyssey series, and I suspect the designers behind that series and I would get get along very well in reminiscing about the ‘good ol’ days.’ Aside from that series, however, a map that shows you all that you have explored is now made immediately available to you with the simple press of a button.

|

| The map in the original Dungeons & Dragons box set. Boy did I spend hours pouring over this one. |

From a playability point of view, and from a user interface perspective, this makes sense, of course. I can only imagine how confused someone less experienced in the dungeon crawler would be if they started to play a ‘crawl and then find themselves hopelessly lost because they didn’t realise that they needed to buy a book of grid paper to go with it. It would be like opening a Christmas present and then discovering that it needed batteries (not included); no one thinks to buy batteries to go with gifts these days, because it’s just assumed that they’ll have rechargeable batteries built into them. When there’s a gift that does require batteries, everyone gets annoyed because the gift is effectively useless until the stores open on Boxing Day.

It’s the same with the dungeon crawler. People are so used to the convenience of not having to map, that the genre is now built around a pace of rapidly moving around the world and occasionally pulling up the map to check the direction that you’re heading. A game that were to require players to draw lines onto a piece of paper is one that would be rapidly dismissed as having a quaint idea that drags the pace of the experience down considerably, and that would only limit their potential audience more.

It is, nonetheless, a real pity, because the genre has lost some of that sense of adventure and mystery in taking the responsibility for mapping away from the player. It doesn’t quite feel like you’re helping a party of brave heroes delve deep into a crypt festering with the undead when half the work is being done for you. It would be like if the early explorers that discovered places like Australia and America didn’t need to keep records because their maps were automatically updated as they sailed; sure, that would have made the journeys safer and far more convenient, but those works of art that were early cartography maps of the coastlines of these countries would be lost to us.

|

| Might & Magic 1. This is why you needed grid paper to play this. It was so easy to get very lost. |

I still have that box of maps from my early PC playing days. Yellowed and faded (as much from overuse and constant referencing back to them than anything else), I’d never think to claim they were artistic masterpieces like the maps that Columbus and Cook brought back, but they are, nevertheless two things that I can’t help but get nostalgic over; firstly they are tangible memories of my childhood in playing these games, and, secondly, they are are reminder of just how much fun it can be to simply explore a game’s world, when the exploration is left to the initiative of the player, rather than the game’s engine.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld