Game theory by Matt S.

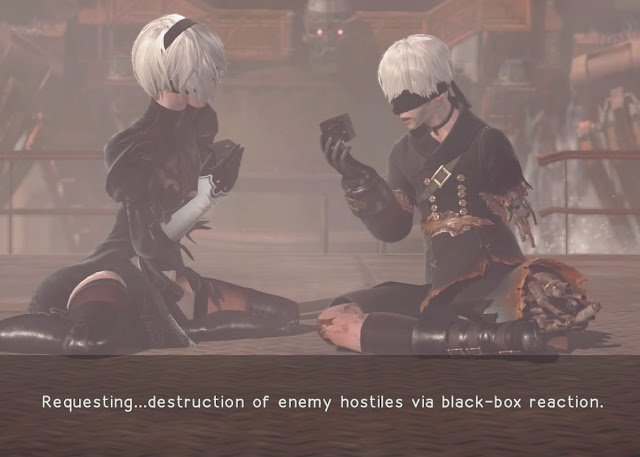

Just before Christmas, Square Enix published a demo for the upcoming NieR: Automata. In a year that includes Persona 5, the sequel to my favourite turn-based JRPG ever made, and Blue Reflections, a game from my favourite game developer (Gust) featuring some of the most beautiful girls ever drawn into a game (and thus a game that very much appeals to me), NieR: Automata is effortlessly my most anticipated game of the year.

Indeed, after playing the demo myself I came away fully expecting that it would replace its predecessor, NieR, as the best game ever made.

What impressed me more than anything is that, unlike with the original NieR, I’m not standing almost alone as a critical voice in praise of the game. Automata’s predecessor was a cult game at best; it performed miserably at retail, to the point that Square Enix never bothered releasing it digitally and has shown no inclination of doing a HD remaster, despite that being a good idea in the lead-up to the sequel’s release. The critical response to the game was middling at best. It would be an almost forgotten release, but for whatever reason the game’s reputation has grown as time has gone on, and the reputation it has now would place it as a real classic. It’s almost – almost – like how Citizen Kane was almost completely forgotten, until it was rediscovered and has subsequently become one of the most important films of all time.

What is odd about the write-ups I’ve seen of NieR: Automata, however, is that far, far too many of them are attributing the game as a “Platinum” game. Platinum was involved in the game, yes, but this response has reminded me of a rather significant issue that we have with how we attribute games in the industry.

With very few exceptions, the games industry tends to attribute a game to the team responsible for the production of the game. This in turn can go two ways; either the development team itself is credited with the production of the game, or, alternatively, the publisher is. So for example, PlatinumGames gets credited with the production of NieR: Automata. The production of a Samurai Warriors or Dynasty Warriors game gets attributed to a nebulous entity called “Koei Tecmo.” Nintendo is constantly credited with the creation of Pokemon Go, despite Nintendo’s only role in the game being its association with Game Freak, the owners of the Pokemon Go rights (and Game Freak in turn wasn’t the producer of Pokemon Go).

|

| Goichi Suda, the creative behind Lollipop Chainsaw, is one of the few game directors attributed by name for his work. |

Gaming is the only creative industry where credit for a game goes to a collective entity that works on the development of the end product, or even the marketing and financing function behind the IP. Consider the film world; films are almost always credited to the director. The Avengers is not a “Marvel” film (by that I mean everyone knows it’s a Marvel license, but no one attributes creative control to Marvel). Rather, it’s a Joss Whedon film. This system has issues in itself as it tends to overlook the other critical creatives involved in the creative decision making behind a film; the screenwriter, for example, but at least in the film industry we attribute it to a person in a creative function.

For an even more explicit example, the way we credit game development is like giving credit to Little, Brown Book Group as the publisher for Harry Potter, rather than J.K Rowling, or giving credit to the Sydney Opera House for having a performance of Swan Lake in it, rather than the director of whichever ballet was taking place inside the building. The role of a publisher in book writing is not dissimilar to the role of a game publisher; the book publisher provides the finance to the author to get the book written, provides editing and support services to make sure the book is best primed for sale to the market, and then handles the PR and marketing efforts behind the book. And yet, at the end of all that, we (rightfully) credit the writing of the book to the author.

NieR: Automata is not a PlatinumGames game. It’s a Yoko Taro directed-game. As with the film industry, Yoko has had significant creative input from other artists; the composer, Keiichi Okabe, especially, but ultimately it is a game by Yoko Taro. Square Enix is the money and marketing function, and PlatinumGames is like the grips, cameramen, production assistants, assistant directors, and the other thousand odd jobs that the modern film has supporting the director’s vision.

It’s an important distinction to make, because without properly attributing a game, we can’t start to properly analyse the creativity that goes into a game’s development. People write books about Steven Spielberg’s unique approach to making films, because it’s different to the way Martin Scorsese or Tim Burton makes films. These directors are often backed by the same producers and sources of money, and indeed often have the same “secondary” creatives working on their respective films, but we can only analyse the films in the context of one another because we attribute them to a single director. Or to put it another way: we can analyse the films of Spielberg because each film belongs to a creative tradition (his own), but it would be pointless trying to break down and analyse the works published by Universal Pictures, because the company publishes so many films from so many different creatives that the library is an mess of theme and style with no common creative threads distinctive to what other film production houses offer.

It would be of benefit to us to look at games in the same way. NieR: Automata is very different from some of PlatinumGames’ other work (especially the likes of The Wonderful 101 and Star Fox Zero) because each of those games have very different directors leading them. NieR: Automata is a Yoko Taro game, and shares more in common, thematically, with NieR and Drakengard than is does with Bayonetta or Vanquish.

|

| Would the Final Fantasy XIII games be analysed differently if they were credited to the director, rather than Square Enix? |

Adopting a “director first” approach to game attribution would also help us explain differences in some franchises that aren’t really similar to one another. Take Final Fantasy for example. Lightning Returns: Final Fantasy XIII is a hugely controversial title. It’s also a Motomu Toriyama game. Rather than simple analyse the game as a “bad” Final Fantasy title (not that I agree that it is, but I do realise I’m an outlier with that game), it would do the creative development of the industry a great service to instead analyse it as a Toriyama game, and then analyse Final Fantasy VII as a Yoshinori Kitase game; a very different director with a very different creative vision. That, then, allows us to recognise that where Kitase’s games do hold a much greater mass-market appeal, Toriyama’s work tends to be more obtuse and philosophically dense, and thus likely to appeal to a far smaller audience. It’s not that one is a necessarily “bad” Final Fantasy game when compared to the other. It’s just that they’re created by very different creative minds and therefore could never hope to be similar in design and appeal.

Ultimately, the reason that games tend to be attributed to the producers or marketing function is because they are still largely seen as products, rather than creative works. The film industry was at that point once, too, back in the 20’s, 30’s and 40’s. It was, unsurprisingly Orson Welles and Citizen Kane that really started to drive this idea that films, as works of art, needed to be credited to the person with the creative sign-off. There are some game directors that have transcended the way we generally attribute games; Shigeru Miyamoto, Goichi Suda and Keiji Inafune are all examples of directors that are credited by name when they’ve worked on a game in a substantial capacity. But those are exceptions to the rule, and in order to continue to develop the conversation around games as art, we need to turn those exceptions into the rule.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld