Review by Harvard L.

NORTH is a wonderfully thought out art game about the current refugee crisis, drawing influence from cyberpunk and surrealism. A lot of people are going to be scared off by this sentence alone and write the game off as a walking simulator. If you aren’t though, you’ll probably want to experience this one without any more information than I just gave you, so stop reading this, go play it, and come back for some analysis. Running at a total length of 40ish minutes, North is absolutely worth your time. Now, an arty game like this deserves an arty review, and I’m totally okay with spoiling the daylights out of it to properly critique it… so last warning, guys!

Okay! Let’s talk about Half-Life. I know NORTH has nearly nothing in common with Half-Life, just bear with me for a little while. In the original Half-Life, developed by a young Valve Software, you play as an ordinary scientist who needs to defend the world from an alien invasion. The aliens in Half Life are weird and grotesque, looking almost like real world animals gone horribly horribly wrong – there’s the 50-eyed dog, the poison spitting hippo thing and the ever lovable and terrifying headcrab. If you think about the context of Half Life, there’s a big fear of science running underneath the subtext of the game, but aside from that the monsters are all very detached from reality. There’s no political statement to be made in the enemy designs, except maybe the long debated question over whether scientists should play God.

Now, let’s talk about Half Life 2. The enemies in Half Life 2 are the Combine – intergalactic conquerors bent on invading territory and enslaving the local population for their evil empire, or something. The Combine aren’t the weird, pseudo-scientific aliens from Half Life though – they look like humans, only wearing very futuristic battle armour. The invasion of humanoid enemies with high tech weapons is significantly scarier when one considers a few tragic events which occurred between 1998 and 2004; events that catapulted terms like “police state” and “domestic terrorism” into the general American vocabulary. Because of the political climate, the audience is more inclined to interpret strange humanoids in battle armour as invaders. I’m not saying that Half Life 2 is necessarily influenced by these events, but I am saying that these contextual events certainly influence the emotional response we receive from consuming science fiction. No matter how far into the fantasy side a sci-fi story veers, it always has some grounding in reality which is often political, and ignoring this grounding devalues the sci-fi as a whole.

Now, let’s talk about NORTH.

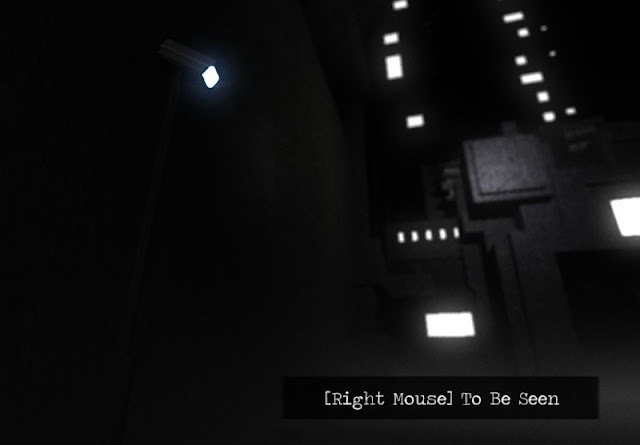

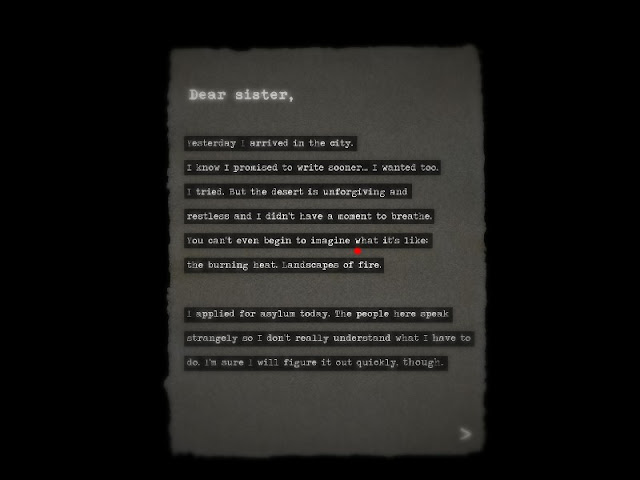

NORTH is a surreal representation of the very real ordeal refugees face to get settled into a western country. You play as an unnamed (?) protagonist writing letters to his sister and her family after arriving in the NORTH, a sprawling mega-city after an escape from the harsh deserts in the SOUTH. Waking up in dingy, falling apart shared housing with your fellow refugees, you must prove yourself capable of work, give evidence that you’re not a terrorist and pledge complete subservience to the state. There’s nobody to help you or to guide you on your journey either – if you get stuck, you need to find a mailbox and send a letter to your sister outlining your experience. She won’t reply, but reading the protagonist’s own thoughts is generally enough help to form a solution to the puzzle, and sometimes the protagonist will just outright tell you how to solve it.

These activities are handled through little set pieces nestled in businesses around the city. This is where NORTH gets both very political and very surreal. You experience everything through the eyes of the refugee protagonist, which in a sense lets us see the other side of the bureaucracy hell many western countries put refugees through in order to “protect our borders”. You need to be able to see past the surreal exterior of the game to realise that the story it is telling is largely grounded in the realities of the present day.

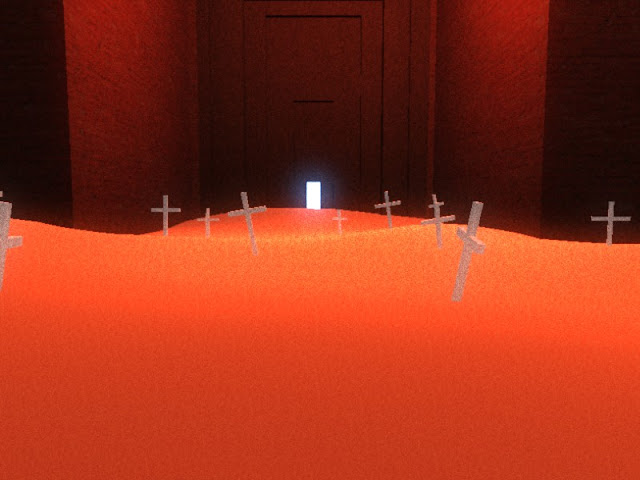

In proving that you’re capable of working, NORTH sends you down into a dangerous mine to extract stones (and it’s never explained why they’re even valuable), with a time limit before you quite literally die. This reflects how in reality, many refugees are forced into unskilled labour as they have often experienced disrupted education, leading to dangerous jobs which they can’t turn away from as they risk being branded a drain on society. The political statement being made is fine – my gripe is with the subtlety with which it is conveyed. The visual and aural design of the mines is fantastic and I love that you need to buy an energy drink from a vending machine to be strong enough to finish your job. What I don’t like, however, is the mass grave of dead workers right between the vending machine and the mine entrance. The mining minigame is already difficult enough that you’re likely to die before finishing the first time: the mass grave is (and pardon the pun) overkill.

My absolute favourite moment though is the terrorism trial at the police station. You are placed in a dark room within a circle of television screens, each with a small loop of grainy, black and white footage. On each screen is a green button and a red button, and a lump rose to my throat as I realised exactly what I needed to do to pass this test. You see, some of the images are of Caucasian children playing around and having fun. Others are of grown men of non-White ethnicity, spliced with still images of human anatomy; a reference to “cultural artworks” you find lying around the refugee apartment. To any refugee or migrant, the ultimatum here is explicitly clear: deny your cultural heritage, or never find asylum in our country.

NORTH is full of gut wrenching cinematic setpieces like this. A particular favourite trope used by the developers is the light at the end of the tunnel, only to be snatched away. For example, upon unlocking the second floor of the city you’re allowed to head straight for the immigration office – a tall, lit up building down a long glittering hallway. Like Dorothy through the streets of the Emerald City you bolt for the doors of your freedom only for all the lights to turn off upon your arrival: you’re not allowed in until you convert to the dominant religion. Over and over you have freedom dangled in front of you until it’s snatched away again, and somehow the experience strengthens you and makes you want to reach the goal even more.

The result was an experience so surreal and immersive that I didn’t even bat an eye when I clipped through a wall in a later sequence and subsequently ruined my playthrough. I walked for a good minute through inner-wall-land before realising it wasn’t an intentional part of the design, and left feeling disappointed after. Upon a second time all the tricks NORTH plays to engage you aren’t as novel, so I think you’d need to pray that all goes well on your first playthrough so that you can experience the story in one whole sitting.

While I would love to see the technical issues fixed as soon as possible, NORTH already makes a name for itself as a competent piece of digital art allowing audiences to develop empathy for the refugees currently trapped by western immigration systems. It’s a brief, lonely, frustrating game that you need to be in the right state of mind to appreciate and honestly belongs more in an art gallery than it does on Steam. Writing a critique of NORTH was a lot of fun, and I do feel glad that Outlands decided to take all the risks involved with developing a game like this.

(Editor’s note: And this is especially applicable to Australia, given we currently have a government and public verges on celebrating when asylum seekers, imprisoned in concentration camps, self-immolate out of sheer desperation to get out of the detention. Someone needs to force the “honorable” Peter Dutton to play this game until he learns some empathy… and it should be mandatory for every Australian that supports mandatory detention besides).

– Harvard L.

Contributor