Review by Matt S.

It’s been a long time since I last played a game that was truly operatic in tone. There have been titles that have effectively latched on to some of the thematic pulls of the art form, such as Pandora’s Tower and Nier, but to find the last time that we had a game that explicitly attempted to emulate the experience of going to the opera was back on the PlayStation 2 with the sadly forgotten Chaos Legion.

Related reading: We don’t have a review of Chaos Legion on this site, but for a game with a similar tone to Nights of Azure, consider Pandora’s Tower on the Wii.

Back then the game was poorly received thanks to direct comparisons that people made between it and the far less nuanced Devil May Cry, as the two shared some superficial similarities around the visual engine (and the fact both were produced by Capcom). Sadly, where Devil May Cry has remained, Chaos Legion has disappeared, but if it does ever lands on the PlayStation 4 as a rezzed-up PlayStation 2 classic, I really recommend giving it a spin, because the operatic elements have gave the game a pacing and thematic underpinning that is almost unique, and the lofty ambition to try and bring the highest of all performance art forms to video games, raw as it was, resulted in something really quite special.

This isn’t a review of Chaos Legion, but it’s a good way to into to Nights of Azure, because Nights is very much Chaos Legion’s contemporary in the way it not only appropriates operatic ambition, but genuinely tries to emulate it. Perhaps not surprisingly, it also plays just a touch similarly to that classic.

Posted by Digitally Downloaded on Tuesday, 29 March 2016

Nights of Azure stars Arnice, a half-human, half-demon vampiric creature that in theory works for the side of righteousness by following orders from a shadowy organisation called the Curia. The Curia organisation seems to exist for a single purpose – to prevent the end of the world at the hands of the powerful God-like demon that is looking to spread a literal darkness through the world.

Unfortunately, the only way to seal away the power of the God-like demon at the core of the spread of darkness is for generations of nominated Saints to periodically ritually sacrifice themselves. And unfortunately for Arnice, this cycle’s saint happens to be her girlfriend, Lilysse. Yes, you read that right; girlfriend. Nights of Azure isn’t even slightly subtle that the core drama is the tragic situation where Arnice needs to protect her lesbian lover to the end that she can sacrifice herself to a cause would would not defeat the great evil, but rather defer it.

It’s the kind of nihilistic fantasy set up that will not be unfamiliar to anyone who has frequented the ballet or opera. Though the lesbian love angle is fairly new to the form, for the rest of it it’s a vintage theatrical tragedy set up. It would have been easy for such a plot to be a cheap, nasty piece of cheap exploitation, but Nights of Azure treats the material with the richness and depth of emotion that it would be granted in an opera proper. The relationship between the girls is presented as romantic, not sexual, and by turns both melancholia and anger comes to the fore as both girls alternate between trying to come to terms with Lilysse’s fate, and trying to find an alternate solution that would mean she didn’t need to sacrifice herself for a greater good; a claim to righteousness that Arnice, especially, isn’t even that sold on.

Especially touching is the scenes where Arnice enters Lilysse’s dreams, the Altar of Jorth, which in terms of gameplay mechanics is how she levels up and acquires new skills. In this dreamspace she’s given a brief few moments to question the dream version of Lilysse, where she’ll have the chance to either learn more about what’s really at stake in this particular quest, or alternatively understand Lilysse’s deeper feelings about what’s going on. In this place, accompanied by an achingly tranquil musical score, both girls are stripped almost naked, in reflection both of their inabilities to lie to one another in this space, thus exposing themselves completely to their partner, and also of the intense vulnerability that underpins their broader relationship. It’s bittersweet, masterfully written stuff, of a depth and standard that we so rarely see in games. And further deepening its impact is the revelation that even here the overarching, sad, theme of loss is prevalent; while Arnice remembers each dream in entirety, Lilysse remembers none of it, making their real world interactions between the two tinged with the understanding for us, the players, that that pure, intimate, connection between the two is forever fleeting.

These themes won’t be unfamiliar for people who have spent significant time at the opera. In fact I would be very surprised if the creative team at Gust are not deep fans of opera themselves. Woven through the game are direct references (that are simply too perfect to be accidental) to La Boheme, Giacomo Puccini’s masterpiece of tragedy that explores the lives of a couple of bohemians. Just as Rodolfo and Mimi from that opera are free spirits living as outliers to mainstream society, so too is the relationship of Arnice and Lilysse’s. We know that in their past they lived together, and it too is their sexuality presented in such a way that suggests they fully indulged the alternative lifestyles of students. Though they never need to struggle with rejection from certain corners of society (the rest of Nights of Azure’s cast thankfully treat their relationship without the need to pass judgment nor attempt at humour), the respective roles of both girls, now as adults, make it clear that they’re nevertheless on the outer of “normal” society nonetheless.

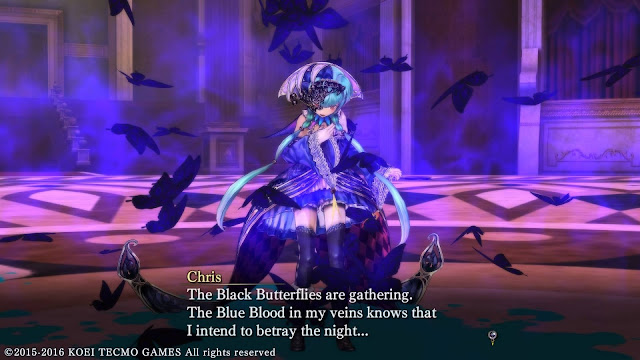

Also similar to opera is the narrative’s love of exploring a binary opposite as a moral theme. In Nights of Azure this is explored through colour motifs of all things; things that are ‘good’ have red blood. Things that are not have blue, and furthermore that blue blood corrupts all that it touches. Over and over again Arnice is told that she needs should embrace her demonic side and consume the blue blood to enhance her powers. Again and again she resists, desperately trying to cling on to her humanity. But blue blood is also a core currency that she can provide at the Altar of Jorth to level up, and summon demonic helpers into existence. So it is difficult to see Arnice as a righteous hero herself when she is so heavily invested in the exchange of and use of the blue blood. Moral conflict is perhaps not explored as comprehensively as I might have liked in Nights of Azure, sitting more as a faintly philosophical theme working in the background, but as something supplemental to the tragic romance is does work to remind us that this tale is a fundamentally dark and grim one, even through the bright and colourful aesthetic.

Supporting that theme is the music score, which really does hold down the emotional weight of the game. Consider other games that make demon summoning and similarly dark themes central to the experience; the entire Shin Megami Tensei series, for example. Where those games make heavy use of rock music themes to underscore an angry, angst-ridden narrative, Night’s of Azure’s soundtrack is more subtle. At home base a laid back jazz track hums through the ambience. When the girls are sharing an intimate moment the music is achingly melancholic. Even in the thick of the action, where the pace of the music picks up, there’s more melodic, soaring series of themes that play through the music than the guttural guitar work of a Shin Megami Tensei. With environments being quite simple, but visually striking, and very much in keeping with the typical simplicity of opera sets (after all, you’re meant to be focusing on the characters), that soundtrack perfectly sets the scene for the amusement parks and churches that Arnice will be fighting in. And perhaps it’s no surprise given the game’s inspiration that the opera house itself provides some of the most striking moments of all, both in terms of visuals and musical score.

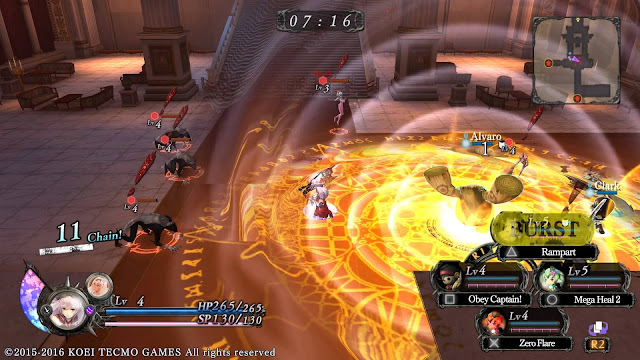

The gameplay itself also reflects that interesting conflict that Arnice has in fighting against the night while also belonging within it. Her chief weapon in fighting against the enemy demons is her ability to summon demons of her own to fight for her. Each of these demons has different roles in battle – some act as defensive tanks, while others hurl balls of flame around, and others run around the periphery of the environment and take on the weakest enemies. Arnice can have up to four fighting by her side at any point of time, and it’s important to build a good, balanced “deck” of the creatures, because Arnice’s own combat abilities are surprisingly limited (as the game progresses she’ll be able to create up to four different decks of monsters and swap between them as needed on the battlefield). Her base attacks don’t do much damage at all, in fact, and while she has a powerful magic attack as well as the ability to temporarily turn herself into a demon, which enables her to cause massive damage for a while, both of those are extremely limited in how frequently they can be used, so without the demon helpers, Arnice wouldn’t last so long in the hostile environments that she explores.

And that’s where further similarities to Chaos Legion come in. In that game your hero was also relatively weak by himself, but had the ability to summon into existence a small unit of creatures to act as both sword and shield. Nights of Azure does it better though, offering a far larger range of allies to recruit, and a little like with Pokemon, building favourite parties and watching them level up together is half the thrill of the gameplay loops.

Also similar to Chaos Legion, the action in Nights of Azure moves quite snappily; environments tend to be small, filled with frequent combat, and there’s even a time limit so you don’t have too long to explore. After 15 minutes you’re automatically returned to the hotel that acts as a hub between missions. That’s more than enough time to get what you need done – not once when I played through the game did I run out of time before achieving a key progression target – but it’s an effective way to keep driving you forward, and helps to enable a kinetic approach to adventuring and combat that hides the relative simplicity and repetitiveness of the underlying systems.

As Gust’s first game on the PlayStation 4 it’s easy to see that the team was still in the process of developing assets and the engine for the new hardware. There’s any number of smokes and mirrors at play in this game to conceal the relative brevity of the content. The environment is broken up into tiny stages, and those are linked through a map system that really only offers two dozen or so places to explore. Enemy designs are repetitive and to try and pad things out further Gust encourages players to spend a fair amount of time in a dedicated arena sub-game, where you’ll try and better times and scores in exchange for loot.

None of this really matters to me, because I was so invested in the narrative, which Gust did give the time to develop properly. Meanwhile, the other key way that the gameplay hours were padded out I downright approve of. The side missions require that you do the standard kind of things that JRPGs like to throw at players as busywork; you’ll slay a certain number of enemies to complete one. On another you’ll need to reach a specific place in the level. That in itself isn’t so special, but these side quests are used by the creative team to inject much-needed levity into an otherwise intense narrative. In doing that, the side quests also help to flesh out the characters and that in turn makes their more serious moments more impactful.

The actual combat flows with the speed and grace of a good ballet. Arnice is a lithe, energetic combatant, ducking, diving and slicing with speed and precision. Her allies fill the screen up with pyrotechnics and lights. It can become disorientating when you’re trying to keep track of everything going on at once, but by staying mobile it’s relatively easy to avoid damage for long enough to reorient yourself where necessary. Arnice herself moves around the environments with a catlike grace and speed. At first it’s a little at odds with the more complex, precise movements that we’re used to with modern games (just try playing this after a Souls game), but after a while the speed of the action complements the rhythm of the storytelling; it’s almost ravishing in the energy it demands, but while, after each long play session, I felt drained, I also felt at every stage that I was participating in something so incredibly lyrical and poetic… and I’ve always taken it as a complement for an opera if I come out the other end in a drained and reflective mood.

More than anything else, though, I really do want to re-emphasise just how special it is to me that the team at Gust have, deliberately or out of pure luck, created something as rare as a genuinely operatic video game. Nights of Azure leaves plenty of room for refinement. Not in a straight sequel, because I believe the story here wraps up in a beautifully, achingly complete package. Rather, there’s room to explore this fantasy with a new set of characters and approach to storytelling with greater refinement and depth on the mechanical side of things.

That there’s some rawness to the overall package is not a criticism of this particular game by any means however. Oh no. Nights of Azure is such a progressive, artful and rich experience that, much like other masterpieces such as Nier of Pandora’s Tower, is so incredibly special as much for its flaws and individuality as what it does well. This game has been more meaningful to me and had a greater emotional impact on me than any game I’ve played since Nier itself, and as far as I’m concerned that means it’s as close to perfection as games can get.

– Matt S.

Editor-in-Chief

Find me on Twitter: @digitallydownld